By Teresa Curristine1 and Joana Pereira2

Brazil continues to face massive infrastructure needs, notwithstanding decades of government-led national, regional, and local investment initiatives. With a large and growing economy of over 200 million people and a vast territory of 27 diverse states, infrastructure needs to help Brazil achieve its economic growth potential are particularly critical in the transport sector (including ports, rail, and roads). At the same time, Brazil also continues to face large social infrastructure investment needs, including, for example, in health.

More efficient investment needed

Our analysis shows that most countries struggle with large efficiency losses in infrastructure investment: on average, 30 percent of the potential impact of public investment is lost, mainly due to inefficient spending. Better infrastructure governance, that is, stronger institutions for handling public investment issues, would help getting more bang for the buck—reducing efficiency losses by up to two-thirds, and doubling the impact of investment on overall growth.

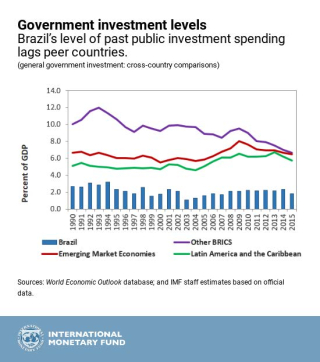

In Brazil, both level and efficiency of past public investment spending lag behind peer countries. During the period 1995 to 2015, general government public investment averaged around 2 percentage points of GDP, compared with 6.4 percent for emerging markets and 5.5 percent for Latin American countries. At the same time, Brazil’s estimated ‘efficiency gap’ in producing infrastructure—a comparison of Brazil with the most efficient countries with a comparable level of public capital stock per capita—is about 39 percent, wider than the average for emerging markets (27 percent) and Latin America (29 percent).

Public investment management assessment

Our most recent assessment reviews Brazil’s infrastructure governance policies and practices and makes recommendations to improve infrastructure efficiency and quality. The report uses the IMF’s public investment management assessment framework, which has already been employed in nearly 50 countries.

This framework identifies 15 institutions that shape decision-making at the three key stages of the public investment cycle— (i) planning sustainable investment across the public sector; (ii) allocating investment to the right sectors and projects; and (iii) implementing projects on time and on budget.

Most infrastructure governance institutions in Brazil are neither particularly strong nor particularly weak in their design. However, implementation varies, and overall institutional effectiveness is weak—this is particularly true in the allocation and implementation phases of public investment projects, less so in the planning phases.

Brazil’s infrastructure governance institutions are relatively strong in the areas of budget comprehensiveness, company regulations and monitoring of assets. The most significant weaknesses arise in the strategic prioritization of investment and project selection and appraisal.

Also, our analysis indicates a lack of high-level guidance on investment priorities and of central guidelines on project appraisal and selection. These weaknesses can result in the selection of low-quality projects.

Also, our analysis suggests that there is much room for strengthening coordination across levels of government; capacity at subnational levels and among some spending ministries, project management and funding certainty. These factors can contribute to weak project execution, cost overruns, delays and poor-quality infrastructure.

The way forward

So, what can be done?

Reforms that seek to address these challenges are already underway in different areas. For example, the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Management is developing central project selection guidelines. The legal framework is being reformed so that a national investment project pipeline can be prepared.

Our assessment makes several additional recommendations that would increase the economic and social returns to public investment. These include the following:

Increase budget flexibility and develop a medium-term budget to improve the predictability and planning of public investment. Given the constrained fiscal environment, there is limited room in the budget for public investment. Reviewing mandatory spending, indexation practices and tax expenditures could create more spending room in the budget for public investment. Most investment projects have a medium-term timeline. Strengthening the medium-term perspective on fiscal and budget management would create a more realistic alignment between planning, budgeting, and the availability of public funding.

Optimize the strategic prioritization of public investment and develop a prioritized portfolio (bank) of high quality projects. For this, it is important to prepare a national strategy for investment which focuses on a national vision and broad strategic objectives, and to develop a prioritized portfolio of large, high-quality projects. As highlighted in a recent IMF study it is also important to improve the transparency of project selection and appraisal.

Improve the coordination between federal and subnational governments in investment planning, as well as in reviewing funding mechanisms. This means finding a better balance between the need for federal oversight and greater devolution of accountability to subnational governments. It is also important to build subnational capacity in public investment management and reduce the fragmentation of federal funding; and pilot a program-based approach to transfers for social infrastructure projects in one or two high capacity states.

Strengthen and standardize the procedures for project preparation, appraisal and selection, and codify these procedures in legislation. The government should introduce central guidelines to standardize processes of project appraisal to be applied to all capital investment.

Enhance project management capacities and accountability. The government would benefit from preparing a decree that assigns responsibility for the management of public investment projects to specific project managers and develops comprehensive guidelines for project management across government.

Modernize public procurement and improve transparency. It is important to update the procurement framework for major projects by removing barriers to foreign participation, enhancing competitive outcomes, and striking a better balance between price and quality in project bidding. These changes would help to address corruption and bid-rigging practices, such as those revealed by the Lava Jato investigation, which are a significant contributor to poor outcomes in infrastructure production.

1 Teresa Curristine is a Senior Economist at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department, where she advises governments on managing their public finances. She leads projects and teams working on public financial management issues in Latin America and Asia. Prior to joining the IMF, she worked for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where she ran the Senior Budget Officials Network on Performance and Results and managed projects on public sector modernization and improving public sector efficiency. She has published several articles and edited three books:Public Financial Management and its Emerging Architecture,Performance Budgeting in OECD Countries, and Modernising Government: The Way Forward. She was a lecturer at the University of Oxford from where she received her PhD.

2 Joana Pereira is the Resident Representative of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to Brazil. Previously, Joana Pereira was a Senior Economist in the IMF’s European Department, working with the team responsible for the macroeconomic surveillance of Germany. She has also worked in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs and Western Hemisphere departments. Prior to joining the IMF, Ms. Pereira was a researcher at Erasmus University, Rotterdam. At the IMF, she has conducted research on a number of issues, including housing price valuations, labor markets, social security, fiscal frameworks, fiscal multipliers, and intergovernmental relations in federations. She holds a Ph.D. and a Master’s degree in Economics from the European University Institute (Florence, Italy) and an Economics degree from Nova University (Lisbon, Portugal).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.