The Washington Consensus has dominated global economic thinking for the past 30 years. The London Consensus is an attempt by some of the world’s top economists sponsored by the London School of Economics, to go for a more balanced approach. The Washington Consensus looks at markets while the London Consensus looks at both the markets and the state. As far as fiscal policy goes, the London Consensus adds two additional points, namely the pursuit of fiscal activism and a call for strong institutions.

Washington Consensus on Fiscal Policy

The Washington Consensus focused on three priorities when it comes to fiscal policy. Firstly, it states that fiscal discipline should be pursued to avoid macroeconomic instability associated with excessive debts or monetary financing. Secondly, that public expenditure should be focused on essential areas such as health, education, infrastructure and welfare and that the states should do away with sectoral subsidies. Thirdly, the Washington Consensus states that tax revenue should come by broadening the tax base while holding tax rates at a moderate level. There is no doubt that the above three principles still hold true and many developing nations are in economic distress as they do not adhere to them. Excessive debt accumulation, populist policies resulting in subsidies and a tax net which is narrow is a recurrent theme in many nations.

The Expansion on Fiscal Thinking by the London Consensus

The London Consensus emphasizes the following two new principles as follows.

Fiscal Activism - The London Consensus argues that the government must act as insurer of last resort for the private sector and also be the market maker of last resort. This objective can be achieved through targeted transfers and automatic stabilizers in cases where there are crises such as health pandemics which cannot be privately insured. The London Consensus also argues that financial markets should be sustained as they prevent self-fulfilling crises and stabilize demand. Additionally, in a crisis, the government should be able to borrow at a lower cost than the private sector. Fiscal activism also believes in temporary and targeted deficits during downturns which will be offset during better times.

Preserving Fiscal Space through prudent debt management - The argument for greater fiscal activism also requires the government to retain the ability and the credibility to borrow during downturns. The London Consensus believes that this can be possible by institutional credibility and prudent fiscal management. Strong institutions to maintain strict fiscal discipline are essential. Transparent communications and information to prevent self-fulfilling debt runs and preserving the safety and liquidity of government bonds are part of this thinking. The London Consensus also advocates for a strong global financial safety net through institutions such as the IMF.

Is there a need for the fiscal concepts in the London Consensus?

The two points advocated by the London Consensus on fiscal policy seem to make sense in the evolving global economic landscape:

- Government intervention through targeted transfers and government intervention to preserve markets and the flow of credit during an economic crisis are essential. Government intervention during the global financial crisis in 2008/2009 and during the Covid-19 Pandemic shows how crucial it was to turn around economies towards a path of growth.

- Even more important are strong institutions that can maintain fiscal discipline, whether economies are in recession or performing well. Overall, the ideas of the London Consensus on fiscal policy seem good from a theoretical perspective. But they face some challenges.

Why the Fiscal Policy of the London Consensus may fail?

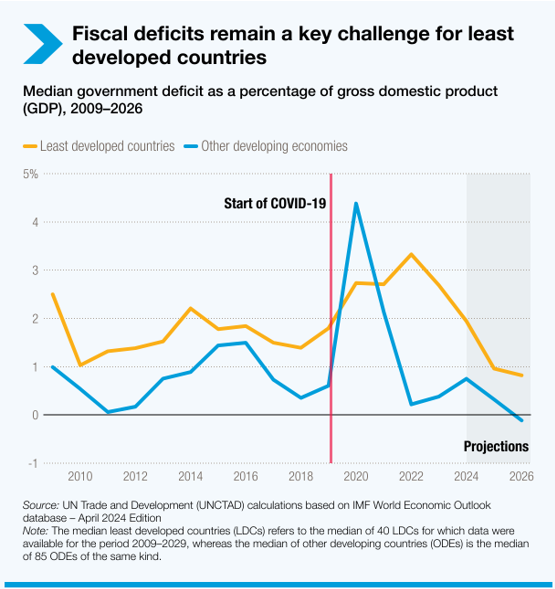

Source: UNCTAD

The key challenge would be the practicality of implementation. Deficit bias is a key challenge, more pronounced in developing countries, but it happens in the developed world too. In an era of populist leadership around the world, it is difficult to maintain fiscal discipline. A fiscal deficit incurred for the purpose of fiscal activism is more likely to continue even when the economy is doing well.

Strong institutions are lacking especially in developing countries where even Central Banks come under pressure from populist leaders to gear monetary policy for political purposes. Prudent debt management is not possible without strong institutions. Credit is cheaper during booms and it is higher during busts. This has been an issue for governments - when they need money, the interest costs are higher, but when doing well, credit is cheaper. This results in greater fiscal indiscipline during good times which will act against the concept of fiscal activism.

Debt vulnerability is much higher for many countries today, as the UN states 54 countries were under debt stress. Unlike developed nations, developing countries have higher borrowing costs. 3.4 billion people around the world live in countries that spend more on debt repayments than on education or health. In this situation, the question is, how practical is fiscal activism if a government is run on a populist platform without commitment to fiscal discipline, and there is little appetite for developing institutions that can act in the interests of the long-term economic interests of the country.

Lastly, there is uneven access to capital for governments as well. Higher borrowing costs of many developing countries contributes to higher fiscal deficits which in turn can lead to larger current account deficits and balance of payments crises. As debt levels in the developed world rise, the idea of a global safety net may also seem less viable, as it has to be led by the advanced economies, who may not have the appetite presently due to their own economic and fiscal issues.

Conclusion

The London Consensus’ focus on fiscal policy is much needed. Fiscal activism can greatly help nations in recession and strong institutions are essential for fiscal discipline. However, deficit bias, fiscal indiscipline, high debt levels and lack of political will for strengthening strong institutions complicate implementation, especially in the developing world. While the fiscal policy of the London Consensus appears promising and may have a greater chance of success in countries with robust institutions, its effectiveness in developing nations could face additional challenges.