Posted by Yasya Babych, Luc Leruth, and Christiane Roehler[1]

Governments’ investment budgets are under pressure as urbanization, new technologies like broadband, and efforts to “green” economies require new kinds of infrastructure. At the same time, and partly as a result, traditional public infrastructure such as roads and bridges but also sewage systems or storm water drainage tend to be neglected. Infrastructure assets can accommodate a lack of maintenance for some years, and even some concomitant increases in demand, e.g., road traffic and, in the time of COVID, pressure on municipal facilities as people work from home. However, over time, capacity constraints emerge, and the erosion of the stock accelerates. Eventually, this leads to costly rehabilitation or even a need for a total rebuild.

Infrastructure tends to be mismanaged. This pattern is known and almost universal as shown by many Public Investment Management Assessments (PIMAs).[2] Estonia is an exception and provides a good example of good infrastructure management. Routine and capital maintenance are estimated both during project design and regularly during budget preparation. Estimates of operating costs and maintenance expenditure are systematically included in a detailed medium-term budget. This information is maintained online and reviewed several times per year by line ministries and the Estonian Ministry of Finance.

When it comes to infrastructure management, planning for maintenance and rehabilitation is usually the weak point, even within Europe. Ireland, for example, has a very high infrastructure quality score overall (according to the Global Competitiveness Index 2019), yet has lower scores on maintenance than Estonia.

In emerging countries, maintenance and rehabilitation planning is an even bigger challenge. For example, in Georgia, recent blogs published by the ISET Policy Institute (Iset) highlight an inadequate basic infrastructure in the capital city’s residential neighborhoods (see also WBk) and growing traffic congestion. These same public goods issues are at the forefront of people’s minds according to a recent survey (Crrc).

Armenia, another post-Soviet transition country in the South Caucasus region faces similarly low levels of perceived infrastructure quality and efficiency. In both countries, PIMA reports found that maintenance funding amounts were determined largely incrementally, based on the likely resources available rather than processes that optimize the life cycle of the infrastructure.

Funds spent on maintenance are essential to ensure that the intended public services are available, and the planned lifespan of the original investment is reached or even extended. Maintenance decisions can also reflect observed or anticipated changes in demand, e.g., by shortening the refurbishment cycle or widening a road. Well maintained infrastructure can deliver a continuously high level of public services. Years of decay do not (see FAD).

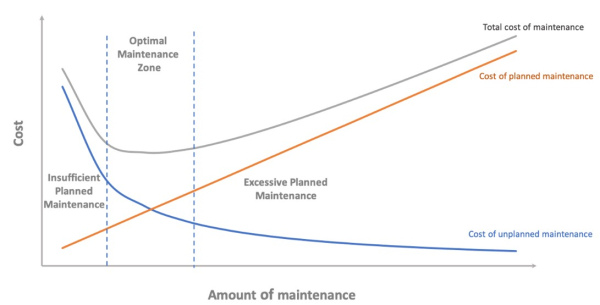

Maintenance is part of a wider approach to infrastructure management. Total maintenance costs are the sum of planned maintenance and the costs of unforeseen maintenance. Figure 1 below shows how both too little and too much planned infrastructure maintenance could result in wasteful spending. If planned maintenance activities such as regular repairs are insufficient, the infrastructure will start deteriorating quickly, and unplanned maintenance costs (replacing failed components) will be high. This, in turn, would result in a high total cost of maintenance. If the amount of planned maintenance activities is very high, unplanned costs may be low, but the total maintenance cost may be higher than necessary. The goal should be to strike the optimal balance as shown below.

Figure 1. Optimal Amount of Maintenance[3]

Unfortunately, there is a fundamental bias against spending on maintenance. Capital maintenance – even if it is replacement for a neglected asset – is reported as an investment item and must compete against new investment projects that are often politically more attractive. Rehabilitation too. Routine maintenance, however, appears as a current expenditure item (IMF, Government Finance Statistics Manual, 2014). This results in a bias against spending more on maintenance since, at least in the first instance, more maintenance spending reduces government savings.

An accrual accounting framework, as it is done in Estonia, helps combat the bias against maintenance spending. This framework systematically monitors the value of non-financial assets, and each year recognizes the physical degradation of such assets. Depreciation is typically recorded mechanically as a share of the historic value of assets (initial acquisition plus reinvestment). Yet, if the state of a physical asset degrades excessively, additional depreciation can be factored into the financial statements.

In short, the core message is to maintain first so as to prevent; rehabilitate when needed; and only start over when necessary. This should lead to more efficient public investments and “better value” overall.

[1] Yasya Babych is a Lead Economist at ISET-PI in Tbilisi; Luc Leruth is a Lead Economist at ISET-PI in Tbilisi and a former FAD staff member; Christiane Roehler is a Senior Economist in the IMF’s European Department.

[2] PIMAs evaluate the quality of public investment management against 15 indicators (“institutions”). They document the level of public investment in the countries assessed, identify partner-funded investment, and estimate a public capital stock. They also look at outcomes, both physical measures of infrastructure availability and the perceived quality of the infrastructure to construct an “efficiency frontier.” Countries that are far from the efficiency frontier could either enjoy better infrastructure with their existing level of spending or spend less to obtain the same outcomes.

[3] Thi Hoai Le, A., N. Domingo, E. Rasheed, and K. Park, “Building Maintenance Cost Planning and Estimating: A Literature Review,” 34th Annual ARCOM Conference, Belfast, UK (2019).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.