Posted by Rui Monteiro[1]

Countries plagued with significant delays in infrastructure delivery often create taskforces aiming at accelerating public investment programs. Although staffed with competent people, and granted high-level, speedy access to the prime-minister or president to whom they usually report, the performance of these entities has typically been disappointing. Their results substantially lag their objectives and aspirations.

Usually these poor results do not reflect a lack of skills or effort, but rather institutional deficiencies in the public investment management (PIM) system. Those deficiencies are analyzed in a chapter[2] of the recently published IMF volume, Well Spent: How Strong Infrastructure Governance Can End Waste in Public Investment. A recent blog in this series, on Fiscal risks from public infrastructure, presents the findings in that book chapter.

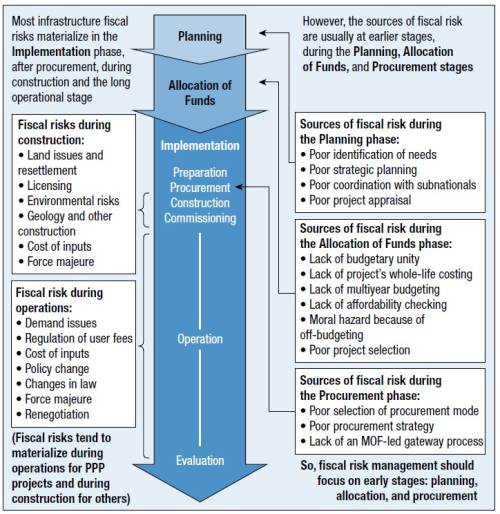

The chapter notes that both fiscal risks and project delays tend to surface in later stages of the public investment life cycle—often during tendering or construction. But their source lies in early stages—typically during planning, project preparation, and the definition of the procurement strategy. In practice, project prioritization is not good enough, allowing poorly assessed projects to be approved, and poorly developed projects to be selected for implementation. Funding is not available for adequate project studies prior to procurement, and procurement regulations allow for immature projects to go for tender. The challenges are summarized in the chart below.

This means that, in many countries, tenders are called for construction without having a completed design. Contracts are signed without being ready for construction to advance. Often government agencies do not have enough resources to prepare projects before resources are allocated in the budget for implementing them. And in most countries budget authorization is valid for only one year. So, when government entities need to execute the budget in a single year, and technical designs are not fully developed, they rush to procure designs and then construction, or even go out to tender without having the design work completed. This a practical recipe for project delays and cost overruns, as typically such projects will face challenges during construction, requiring costly and lengthy change orders.

Having the project requirements fully specified and the technical designs complete is also essential if procurement is to be competitive and transparent. Bidders must be able to cost the project for which they are competing and present their best proposals. The absence of this critical information opens room for opportunistic bidders—the ones better at gaming the government than at building infrastructure. It is not surprising that many projects are delayed, and additional fiscal costs incurred. Pressure for faster implementation—when not preceded by adequate project assessment and preparation—leads to additional fiscal costs, even without any significant acceleration of delivery.

Source: IMF, 2020, Well Spent: How Strong Infrastructure Governance Can End Waste in Public Investment.

To address these challenges, it is encouraging that many countries are reviewing the efficiency and effectiveness of their institutional framework for PIM, using tools such as PIMA (the Public Investment Management Assessment, a methodology developed by the IMF), that assess the whole PIM life cycle, from planning and project preparation and selection, to budgeting and delivery of funds, and to procurement, contract management, audit, and evaluation.

Although pressure for fast project implementation should not be disregarded, IMF research (see IMF, 2015, Making Public Investment More Efficient) shows that significant improvements can result from swift implementation of reforms to the PIM framework. The study finds that, on average, around 30 percent of the potential benefits of public investment are lost due to inefficiencies in the investment process. In many countries, improving areas such as investment planning and project preparation allow for getting more impact out of the always scarce fiscal space for capital spending—a matter that is even more relevant nowadays, when preparing post-COVID-19 public investment plans. Countries with stronger institutions usually have more predictable and productive investments, reducing fiscal risks and implementation delays, and closing up to two-thirds of the above-mentioned efficiency gap.

[1] Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2] Chapter 11 on “Fiscal risks in Infrastructure” by Rui Monteiro, Isabel Rial, and Eivind Tandberg.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.