Posted by Charles Price[1]

Intangible assets: a trillion dollar asset class

Recent years have seen a vibrant discussion of intangible assets - things like intellectual property, skills and know-how. Strong contributions have been made by Baruch Lev, in The End of Accounting, Carol Corrado in Measuring Capital in the New Economy, and by Jonathan Haskell and Stian Westlake in Capitalism without Capital.

These authors highlight that the balance sheet drawn up under traditional accounting rules poorly reflects the overall value of a company because they understate the importance of intangible assets. This gap has been widening in recent years and is particularly noticeable in the world’s best performing companies. The five most valuable companies are worth £3.5 trillion together but their balance sheets report just £172 billion of tangible assets. Their intangible value amounts to trillions of dollars.

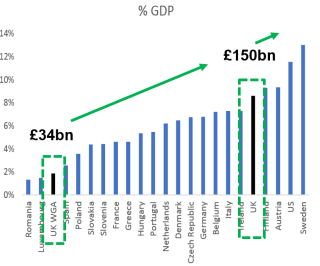

The picture in the public sector differs significantly. The measurement and use of balance sheets lag the market sector, although progress is being made. The OECD and IMF provide valuable overviews in recent papers on “Getting value out of accruals reform” and “Managing Public Wealth”. Understanding of Intangible Assets in the public sector is at an even earlier stage though economists at SPINTAN[2] have prepared experimental estimates. The chart below sets out SPINTAN’s conclusions for a range of countries.

Taking the UK government as an example, the accounting value of its intangible assets is £34 billion as recorded in its Whole of Government Accounts (WGA) whereas the SPINTAN estimate is £150 billion. However, even this larger figure may understate the true value of public sector intangibles. UK and other governments around the world have a long track record of delivering ground-breaking innovation. CT scanners – used in health systems all around the world - emerged as a collaboration between the UK National Health System and the music technology company EMI. US government laboratories played key roles in developing microchips and the internet, originally for the space and defence sectors, but with massive application beyond. Such innovations are not limited to advanced economies: the Rwandan Ministry of Health is developing innovative logistics pathways using drones to deliver medical supplies in partnership with a start-up.

A framework for value

Are these different approaches to valuing intangible assets just a measurement challenge, or can it add real value for fiscal policymakers and citizens? Academics have identified four features that differentiate intangible assets from traditional ones. Their focus is on the market sector, but these features are applicable in the public sector. They argue that intangible assets can be scaled-up at little extra cost; that they are driven by synergies (for example, a dataset in itself may have no value, but combined with a new algorithm it can have huge value), that spillovers are key (many R&D breakthroughs have their most valuable uses outside of the original purpose), and that investments into intangible assets are sunk (unlike an investment into property, where there is generally a ready resale market).

The world’s leading companies and markets have become extremely proficient at managing these features. Leading multi-national companies and start-ups alike excel at spillovers (transporting innovations from one field into another), creating synergies (combining data, skills, business models in novel ways) and scaling up significantly. The operating systems of successful business have evolved to reflect this: incentives, investment techniques, management processes and information pathways have shifted from vertical command-and-control models to ones that favour inter-disciplinary thinking, networking and synergies.

By contrast, in most countries public sector management – financial and operational – usually operates within strong vertical structures. Ministries have defined purposes and limited pathways to work across silos. This does not encourage an assessment of how an investment made in one field could be combined with an innovation in another field. Or how a capability in one area can be scaled up significantly beyond a ministry’s core purpose. Justifying investment in managing intangible assets is difficult when it is outside an organization’s core mission.

Plan of action: establishing new pathways

The hidden value of intangible assets and the potential to increase economic, social and financial returns has emerged as one of the biggest opportunities in a review of its balance sheet that the UK government is carrying out. In 2018 HM Treasury published a report entitled “Getting Smart about Intellectual Property and other Intangible Assets”. Its recommendations are summarised below. A forthcoming strategy document will set out how the UK government plans to implement these recommendations.

Identification: improve means to develop and profile the public sector’s holdings of intangible assets.

Insight: design and implement best practice protocols for understanding and exploiting intangible assets.

Infrastructure: establish increased expertise within government to provide advice and support for managing intangible assets.

Incentives: enhance incentives for knowledge asset development and exploitation.

Investment: develop financial and organisational structures that facilitate knowledge asset exploitation and effective partnerships with the private sector.

Conclusion: creating opportunities

Adapting the value of intangible assets into the public sector creates several opportunities as well as challenges. It offers public sector financial managers the opportunity to be on the front foot regarding how the public sector innovates. It offers innovators within the public sector the opportunity to establish new financial underpinnings for their programmes. It offers citizens the opportunity to benefit from new productivity-driving innovations in the economy, and ultimately better public services, and the stronger public finances that result from this.

[1] Deputy Director, Fiscal, HM Treasury, United Kingdom.

[2] SPINTAN (Smart Public Intangibles) is an EU funded project that has built a public intangible database for a wide set of EU countries.

The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.