Posted by Seyed Reza Yousefi[1]

We all know about government debt. It is widely reported and a key issue in formulating public policy. And we understand that high debt makes countries vulnerable, leading to higher interest charges on this debt. For these reasons, government debt is a key focus in macroeconomic analysis.

But what about government assets? If government were a corporation your analysis would certainly include them. Yet the standard view of public finance does not. What if we were to change that? What would taking account of government assets mean for countries’ resilience in downturns? And if countries with more assets are less vulnerable, would this show up in the interest rate they pay on their debt?

A new IMF working paper addresses these questions. As the point of departure, it looks at the general government balance sheet. This means it analyzes government assets in addition to liabilities. The paper shows the different ways balance sheet information enriches the picture and allows one to look at the source of changes in assets and liabilities. For example, do they come from the sale or acquisition of a building or the contracting of a new loan? Or are they caused by changes in the value of existing infrastructure or oil reserves?

The paper also illustrates that balance sheet strength is not only about overall government wealth—the balance between assets and liabilities. Even when you have a high wealth, do you perhaps have a lot of short-term debt, but very long-dated assets, opening you up to liquidity risk? And how much of your assets are denominated in foreign currency, offsetting currency risk on your foreign exchange denominated debt?

These examples are illustrated for Kazakhstan. In 2014, the Kazakh economy suffered a halving of the oil price—its main export—combined with an economic slowdown in Russia and China—its main trade partners. The economy and with it the Kazakh Tenge exchange rate were hit hard. The paper brings out how balance sheet effects on government assets cushioned these adverse impacts, allowing the government to pump money into the economy to ease the downturn. The Kazakh government balance sheet strength thus increased the country’s economic resilience.

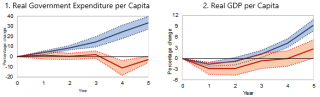

But what does the paper find on resilience more generally? First, countries with stronger public asset positions indeed pay lower interest on their debt. In other words, financial markets seem to pay attention not just to a country’s debt, but also to its assets. Second, countries with stronger balance sheet positions tend to recover faster from downturns and the recession they do experience tend to be shallower (Figure 1). This is mainly due to the greater ability of these countries to expand government spending in a downturn, thus cushioning the economy.

Figure 1. Recovery and Fiscal Policy in the Aftermath of Economic Recessions (Click on the figure for a better image resolution)

Note: Blue line represents sample of countries that entered the recession with a strong initial balance sheet, and the red line is for those those entering the downturn with a weak balance sheet. The sample is restricted to the sample of recession episodes and the dotted lines represent the 90 percent confidence bands.

And what does this mean for policy? Taking a balance sheet approach enriches the fiscal picture by providing a view beyond debt and deficits. It increases transparency and enhances accountability. Balance sheets also present policymakers with a better-informed assessment of fiscal policies and risks, and opportunities to better manage their assets. Such approaches to public wealth are actively practiced in, e.g., New Zealand and the United Kingdom. But perhaps most importantly, understanding the balance sheet allows policymakers to look for the best ways to employ public wealth to meet a society’s long term economic and social goals.

[1] Seyed Reza Yousefi is an Economist at the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.