Posted by Taz Chaponda and Richard Allen[1]

Building large infrastructure is a very difficult undertaking, particularly in the public sector. A lot of things can go wrong during the life of a large project, leading to cost and time overruns and poor outcomes. One of the most intractable problems is political interference in infrastructure development. But how does one separate the purely political issues (that may be legitimate) from economic and technical aspects? And is corruption the core driver of poor outcomes or are there other governance issues at play?

These were some of the issues discussed at a recent public investment seminar in Accra, Ghana. The event, organized by the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF in collaboration with AFRITAC West 2 and the European Union, was attended by more than 50 participants from 23 countries in sub-Saharan Africa and was centered around peer-learning and country case studies. Notwithstanding the diversity of country experiences, most participants agreed that political interference in infrastructure planning and delivery was a pervasive problem.

Of course, the problem of politics in infrastructure is not limited to low-income countries. There are many examples from the UK, for example, ranging from the infamous Scottish Parliament building, whose final cost was a multiple of the original budget, to the controversial third runway at Heathrow Airport, to the proposed high-speed train link from London to Birmingham, the Midlands and the North of England (HS2). The former Treasury Permanent Secretary, Nick Macpherson, has commented that HS2 went forward largely on political arguments in spite of “a low economic return compared to other transport projects”. He went so far as to say that based on “rigorous cost-benefit analysis, HS2 fails that test”. The rising costs of this project has raised serious concerns about its planning, and the decisions that led to its implementation.

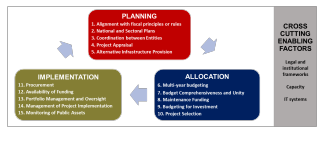

To analyze infrastructure governance-related challenges, the Accra seminar was organized around the Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA). This diagnostic tool, updated in 2018, helps countries grapple with the multi-faceted dimensions of infrastructure governance. The PIMA is a survey-based analysis centered on three areas, namely the planning, allocation and implementation of public investment projects. Under each area, five PIM institutions are defined (see diagram), with a view to identify weaknesses in infrastructure governance that could explain the loss of public investment efficiency.

Click on the figure for a better image quality

This framework suggests that the problem of political interference can operate at many stages of the project cycle. During the planning stage, several things can go wrong. First, projects can be inserted into national and sectoral plans even where the rationale for doing so is weak. Typically, these politically-motivated projects will not be subjected to rigorous project appraisal. Second, is the question of the most appropriate channel for providing the infrastructure. Non-viable projects can sometimes be pushed through a state-owned enterprise or structured as a public-private partnership to bypass the scrutiny of the budget process. Frequently, implementation through state enterprises can be difficult to monitor because vital information is not disclosed and the government does not exercise effective oversight.

When it comes to the “allocation” stage, political pressure can influence the selection of projects. There are usually many more projects seeking funding than available resources. In this case, powerful politicians may push their “pet” projects to the front of the line regardless of their economic merits. The project may not be a bad project per se, but given the available funding, its timing may be problematic. Pushing such projects will crowd out other better candidates that would have a higher impact on growth.

Finally, under the implementation stage, public procurement may be a source of corruption when political pressure is asserted to influence the selection of a bidder. This can lead to collusion and corrupt relationships between the bidder and their backers. A less obvious form of interference would be diverting funding earmarked for one project to another new project. This too can delay project execution and result in payment penalties or higher interest costs for the delayed project.

With so many different avenues for potential political interference, it is important that the root causes are properly identified. While corruption can be enabled by weak procurement practices and controls, the absence of rigorous project appraisal, project selection that circumvents the budget process, and inappropriate funding models can also lead to poor infrastructure outcomes.

Although we may agree that political interference is a major and age-old problem for infrastructure development, there is much less consensus on potential solutions. One approach is to insist on high levels of transparency at every stage of project delivery through reporting to the relevant oversight bodies, including the Auditor General and parliament. This way, the public would know why certain projects have been prioritized in national plans, how they were selected, how they are funded in the budget, and indeed whether the expected impact is in line with the government’s political mandate.

Another approach is to simplify and automate processes for procurement and reporting of results. Corruption breeds on complexity, and the use of e-systems and digitalization can take greedy and dishonest fingers out of the pot. Yet there is also a dilemma to be faced. It is widely agreed that reforming poor institutions requires strong leadership and country ownership. But how to secure that leadership and ownership if the politicians themselves are a prime source of the problem?

[1] Senior Economists, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2] IMF Regional Africa Seminar on Strengthening Public Investment Management (26–29 March, 2019).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.