Posted by Moritz Piatti-Fünfkirchen and Ali Hashim[1]

When Leo Tolstoy wrote Anna Karenina about 150 years ago, he inspired generations. His novel begins

“All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Now, what does this have to do with Financial Management Information Systems (FMIS)? What Tolstoy perhaps meant was that a deficiency in any one of a host of factors dooms an endeavor to failure. Consequently, to make an endeavor successful it is necessary to mitigate against deficiencies and risks in multiple areas.

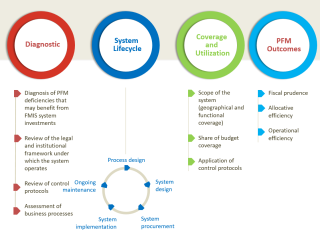

In a recent World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (click here to access the paper) the authors developed a framework that lays out three critical dimensions for an FMIS to contribute to improved budget management: (1) the diagnostic phase, (2) the system’s lifecycle, and (3) the system’s coverage and utilization. The diagnostic phase covers a review of relevant PFM deficiencies, the legal and institutional framework, control protocols, and business processes. The system lifecycle lays out what it takes to make an FMIS operational. Lastly, the coverage and utilization of an FMIS will determine its scope and effectiveness. The framework is shown in the figure below.

Figure 1 A framework for conceptualizing FMIS reform (click on the image for a better view)

The paper argues that Tolstoy’s ‘happy family’ requires attention through all stages of the reform process, and that a system is unlikely to contribute significantly to improved PFM outcomes if the diagnostic is partial, the lifecycle is broken, or the system is not effectively used. While prima facie this statement may appear obvious, in practice the ‘diagnostic’ and ‘coverage and utilization’ phases tend to be crowded out by technical issues related to the design, procurement, and implementation of FMIS. Hanna et al (2012)[2] note that a ‘failure to notice’ can be a key binding constraint and that learning from experience does not necessarily guarantee an effective use of technology.

The authors derive 24 practical lessons through triangulating evidence from case studies prepared by the World Bank’s Independent Evaluation Group (IEG)[3], analysis of the Bank’s extensive FMIS project documentation, and a review of the literature. This information is mapped against the framework outlined above. Below a brief overview of key lessons:

Lessons from the diagnostic phase. It is important to clearly determine the rationale for implementing an FMIS, and identify the problems that the proposed system intends to address through a diagnostic assessment that also reviews the policy and institutional environment in which the FMIS will operate. A partial assessment - focusing only on accounting issues, for example - may lead to sub-optimal solutions. Assessing the adequacy of analog complements - as discussed in the 2016 World Development Report on Digital Dividends - is critical to protect against downside risks. FMIS expedites the speed of transactions. Setting up a system without determining the adequacy of control protocols or business processes could create an FMIS in which ‘the wrong things are done faster’. How to assess FMIS performance was discussed in a recent IMF PFM blogpost here.

Lessons from the system lifecycle. As FMIS reforms take time, they are exposed to political cycles and associated risks. The paper argues that government commitment and leadership are more likely to be sustained if the reform is presented in terms of broad-based improvements of fiscal and budget management rather than narrowly as an upgrading of IT or accounting systems. Commitment and leadership can be fostered through well-designed project management structures and change management strategies.

An effective system design is one that recognizes the larger functional and business process requirements of government. Similarly, experience suggests that system implementation strategies that are phased tend to be more successful than attempting the simultaneous implementation of a wide set of functionalities which overstretch client capacity and dilute the reform momentum. Some countries have experimented with taking a modular approach in systems implementation, which holds promise in being more cost-effective.[4]

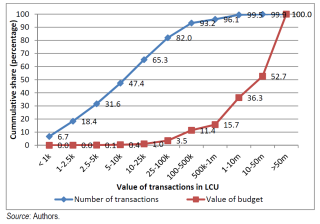

The systems deployment strategy across levels of government is a critical phase in implementation. The working paper finds a striking pattern across countries in the transactions profile with relatively few transactions making up the bulk of the budget (see figure 2 below). For the purposes of expenditure control, this information could be used strategically for early results in the implementation process by focusing on high value transactions. Low value transactions could be integrated through alternative means.

Figure 2 Sample transactions profile by number of transactions and size of budget

In some cases, the lack of an adequate budget for the maintenance of the FMIS - including access to technical expertise provided by domestic resources or consultants - results in insufficient capacity to manage transactions, and may expose the system to various security risks.

Lessons from coverage and utilization. The share of the budget that is routed through the FMIS, and benefits directly from its functionalities, can serve as a good proxy for the system’s contribution to improved budget management. It is important to be transparent about what transactions are subject to the system’s internal controls, and which are only posted to the general ledger after they have occurred. The analysis also shows that the effectiveness of a system can be undermined if commitments are not recorded, or budget releases are delayed.

[1] Moritz Piatti-Fünfkirchen is a Senior Economist at the World Bank. Ali Hashim is a former Lead Treasury Systems Specialist, World Bank.

[2] Hanna, Rema, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Joshua Schwartzstein. 2012. Learning Through Noticing: Theory

and Experimental Evidence in Farming. No. w18401 National Bureau of Economic Research.

[3] Case studies were field based and include Cambodia, Ghana, Malawi, Vietnam, and Zambia.

[4] See recent IMF blog post for examples.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.