Posted by Per Molander1

The role of budgetary institutions is to solve or, at least, alleviate problems associated with collective decision-making in the political sphere. To some extent, the objectives of reform are conflicting, which leads to difficult trade-offs that are both technical and political in nature. Whether a PFM reform attempt will be successful or not will depend on the ability of the reformers to handle these trade-offs.

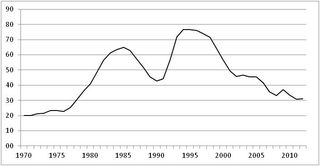

During the 30-year period from the early 1960s to the early 1990s, Sweden went through two major financial crises (see chart below). Only after the second crisis were major changes made to the budget process. By any standard, this reform was a success.

Sweden’s central government debt 1970-2012. Source: Swedish Public Financial Management Agency.

Since the budget reform of the early 1990s, the central government budget, including the social security sector, has shown surpluses almost every year and the government debt-to-GDP ratio has been reduced from over 75 percent to about 30 percent. The public sector has also become smaller in relation to GDP and is now similar in size to comparable OECD countries.

Reform of the budget process was one of the major factors contributing to the turnaround in Swedish public finances 20 years ago. While a financial crisis creates a window of opportunity for reform, it does not guarantee the success of that reform. So what does explain its success? First, a favourable climate of reform had been created in the late 1980s as a result of a major tax reform, a reform of the pension system, reforms in the areas of agricultural and trade policy, and others. Somewhat paradoxically, several reforms may be easier to get through parliament than an isolated one. Second, the PFM reform was based on solid empirical research, using studies that analyzed recent economic and fiscal trends, and modelled the expected impact of the reforms.

Another key factor in Sweden was the broad involvement of political decision-makers. The principal aim of the reform was explicitly to enhance the powers of political institutions, principally by giving them an effective instrument to control and allocate public expenditure. The intention was thus not to move decision-making power away from political institutions and place it in the hands of technocrats or to resort to automatic rules. For this reason, it was important that the core group of reform leaders and “entrepreneurs” included both politicians and experts. This approach was of fundamental importance in explaining the continued and strong political support for the reform.

The main guiding principle was to keep the reform simple but specific. Its principal technical elements were:

• an emphasis on maintaining a sustainable level of public expenditure rather than budget balance, in order to create a fiscal rule that could be directly implemented through the annual budget process;

• a top-down approach to budgeting, both in the government and in parliament;

• a comprehensive coverage of the budget, by eliminating extra-budgetary funds, subsidized guarantees etc.; • maintaining the principle of gross budgeting, i.e., no netting off of expenditure against revenue;

• the introduction of nominal expenditure ceilings set for a three-year period;

• the dismantling of open-ended appropriations (in the social security system also);

• in-year monitoring of expenditure on a month-by-month basis;

• an economic/administrative rating of all government agencies; and last but not least;

• enactment of a new budget act that, among other things, clarified the degrees of freedom of the government vis-à-vis the parliament in the fiscal policy area.

Another important decision of the government was to explain the goals and objectives of the reform to the public in order to gather the necessary popular support. This required a significant pedagogical effort since it was also necessary to explain the basic principles of the budget process. The government endeavoured to ensure that the arguments presented for the reform were positive not defensive. For example, a lot of emphasis was given to explaining the beneficial effects of an improved allocation of public expenditure and well-managed public finances on general economic performance and living standards. Arguments that blame the need for fiscal austerity on the EU or IMF, on the other hand, have little traction with the general public.

The reforms in Sweden did alter the balance of power within the political system. The role of bodies responsible for general economic policy and sound public finances—in particular, the Standing Committee on Finance in the Parliament, and the Prime Minister’s Office and Ministry of Finance—was strengthened. Indirectly, the reform probably also strengthened the ability of the leaders of the political parties in opposition to influence decisions on the priorities for public finances. In Sweden, the voting rules in Parliament in combination with the new parliamentary budget procedure also made it easier for a minority government to get the budget proposal through parliament. This consequence, however, is highly dependent on the micro-rules of voting; here as elsewhere, the devil is in the details.

A recent blog post by Ingvar Mattson (April 11) explains how a political crisis in the Parliament last autumn upset the delicately balanced consensus of budget decision-making that the reforms of the 1990s helped bring about. The fallout from this crisis has yet to be fully resolved.

1 The author is Director General of the Swedish Social Insurance Inspectorate. Further information on the Swedish reform can be found in Per Molander and Jörgen Holmquist, “Reforming Sweden’s Budgetary Institutions—Background, Design and Experiences”, Rapport till Finanspolitiska rådet, 2013/1.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.