Posted by Sierd Hadley[1], Laure-Hélène Piron[2], Gareth Williams[3], and Clare Cummings[4]

The transition to democracy in Nigeria in 1999 raised expectations for change after more than 30 years of military rule. The UK began its support to PFM reforms as part of an effort to translate oil revenues and debt relief into better infrastructure and public services. A new series of papers and webinars led by the Learning, Evidence and Advocacy Partnership of the UK-funded Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn (PERL) reviews 20 years of UK governance support in Nigeria. This research looks at what has been achieved, how and why.

A long-term partnership

The 1999 Constitution devolved responsibilities for the provision of health and education in Nigeria to 36 States and 774 Local Governments. It also guaranteed a share of oil and VAT revenues to help pay for them. However, few States had the capacity to manage these resources well. Some lacked even a basic budget process and there was limited oversight of state budgets by state legislatures and civil society.

The UK began providing support for state-level governance reforms in 2000. There have since been three generations of governance programmes, adding up to an investment of over £275 million. The states of Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano and (more recently) Yobe have all been long-term beneficiaries of this support and are the focus of the research produced by PERL.

The UK’s governance support combined technical assistance for PFM issues such as state budgeting with efforts to strengthen the capacity of civil society, the media, and State Houses of Assembly to hold governments to account. As well as working to strengthen governance, these programmes were also expected to raise the impact and sustainability of UK support to health and education.

Significant, but uneven, improvements in governance

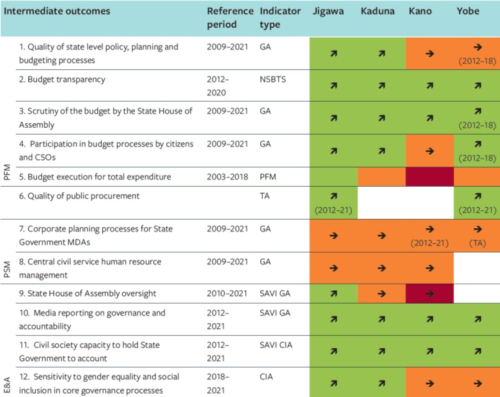

Long-term observers of PERL suggest that PFM capacity at the state level looks very different today than in the 2000s, even if the overall quality of PFM remains low.[5] Nonetheless, the research suggests that progress has varied across the different reform areas (see Figure 1):

· Indicators for empowerment and accountability and budget transparency improved the most. All four states have seen important progress in the general capacity for media reporting and civil society holding the state to account, as well as in PFM such as budget transparency and participation. Scores on the Nigerian States Budget Transparency Survey rose from 1% to 90% for Jigawa, for example.

· The record of other PFM reforms has been mixed. Jigawa and Kaduna have strengthened the links between planning and budgeting, for example. But budget execution rates have remained poor across all four states, with only Jigawa showing sustained improvements over time and execution rates regularly at 90% or above.

· Public sector management reforms proved especially challenging. Efforts to strengthen human resources management (HRM) or corporate planning in state ministries, departments and agencies did not produce clear or sustained progress in any of the four states.

Nonetheless, as an important marker of general progress, Jigawa, Kaduna and Yobe all performed better than Nigerian states on average against the benchmarks set by the World Bank States Fiscal Transparency, Accountability, and Sustainability (SFTAS) Program for Results.

Figure 1: PFM and other governance indicators in four states

Notes: PSM = public sector management; E&A = empowerment and accountability.

Indicator type: GA=PERL Governance Assessment (and previous SPARC Self Evaluation Assessment Tool (SEAT)/PEFA assessments); CIA=PERL Constituency Influencing Assessment; SAVI=SAVI Outcome Indicators; PFM=PERL PFM database; NSBTS=Nigerian States Budget Transparency Survey, Civil Resource Development and Documentation Centre; TA=Team Assessment (qualitative based in interviews and document review).

Trend / performance ratings: green is for indicators that have shown improving trend or relatively strong performance when the timeseries is short; orange captures indicators where trends showed limited or inconsistent changes, and where performance was average; red is for cases where indicators show a declining trend or weak performance in cases with shorter time series.

Source: See Annex 2 of the study on “Twenty years of UK governance programmes in Nigeria” for detailed descriptions and scoring.

Increases in spending and improving outcomes for health and education

At the sector level, the picture is also broadly positive. Despite growing fiscal constraints, Jigawa, Kano and Kaduna all significantly increased the share of public spending dedicated to health and education between 2003 and 2018. Yobe was affected by insurgencies from Boko Haram, but still increased the share of spending on the health sector.

More importantly for citizens, all four states have made improvements in health and education outcomes such as the percentage of women receiving antenatal care from a skilled health provider and primary school enrolment and completion rates.

What factors have made this progress possible?

The research offers more insights than this blog can summarise. In many cases they help explain why change happened in a specific reform area or a specific context. But when it comes to the big picture, three lessons stand out:

Lesson 1: Supporting “political credit” is linked to more visible impact

Unsurprisingly, reforms were less likely to take off and be sustained when they threatened powerful political interests. For example, improving HRM reform was challenging because curbs on the powers to recruit and deploy staff threatened important sources of patronage.

Where PFM reforms have supported lasting change, it is usually because the government has been able to claim political credit and advance its agenda. For example, increasing civil society participation in setting budget priorities was not only less threatening, but it could also enable a given state government, and its Governor specifically, to appear responsive and engaged.

The space for change varied significantly across the four states. Politics in Jigawa is dominated by a small group of elites with limited competition, which has given the Governor room to forge a wide ranging and sustained reform agenda. In contrast, Kano has been mired in political conflicts and highly contested state politics, and as a result, successive Governors have focused more on dispensing patronage than on strengthening PFM systems.

Lesson 2: Building over the long term can help respond to windows of opportunity

Of course, politics can change, and sometimes dramatically. Building capacity and systems over the longer term can lay the foundations for improving PFM results when opportunities arise.

This was the experience in Kaduna following the election of Governor El Rufai in 2015. With weak opposition and his political position seemingly secure, El Rufai has promoted reform to demonstrate his credibility and position himself as a potential candidate for the country’s Presidency.

Building on previous UK support, Governor El-Rufai is using governance programmes to implement his reform vision and prove his leadership skills. He took ownership of the State Development Plan, used it to prioritise sector policies and spending, and is coordinating donor support in the state.

Lesson 3: Linking PFM reforms to service delivery results is not straightforward

Despite the ambition of using UK governance support to help improve the level and quality of spending on primary health and basic education services, the extent to which this has been achieved is not clear from the PERL research.

There are clearly some suggestive links between the UK governance support and service delivery. Efforts to strengthen civil society advocacy and the links between sector policies and the state budget may have increased the priority attached to health and education in the budget.

Yet it is hard to know if this has increased spending on primary level services which are jointly financed with local governments, but also by the federal government and donors. The fact that Kano achieved the largest improvements in health and education outcomes without many governance improvements shows that many factors have been involved – not least off-budget donor support, but perhaps also the degree of urbanisation.

It is still notable that PFM support focused mainly on the state level while local governments play an important role in financing and delivering basic education and primary health services. Equally, UK support programmes working on governance improvements and those working on sector service delivery have a mixed record in collaboration.

These are important lessons that should be considered as part of the next phase of governance programming in Nigeria.

[1] Research Fellow, ODI.

[2] Director, The Policy Practice.

[3] Director, The Policy Practice.

[4] PhD candidate, University of Manchester.

[5] Though somewhat dated, PEFA self-assessment were completed at different intervals between 2007 and 2012. They suggest that all four states average a C or less across the PEFA indicators. The repeat assessments for Jigawa and Yobe indicate some improvements, while Kano and Kaduna had declining scores. However, the lack of quality assurance means that comparisons need to be treated carefully.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.