Posted by Julia Dhimitri and Martin Bowen[1]

The PEFA Secretariat has recently developed and pilot tested a new approach to preparing a country’s PFM reform strategy. The approach aims at assisting countries to identify, prioritize and sequence reform initiatives, and to take charge of their own reform agenda. Volume IV of the PEFA Handbook-Using PEFA to support PFM improvement provides guidance on the new approach.

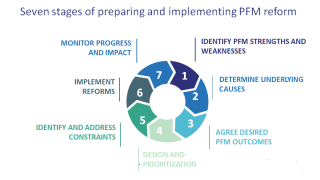

The guidance sets out a simple seven-stage approach to developing and implementing PFM reform initiatives from the initial identification of the problems (including weaknesses identified in PEFA and other diagnostic assessments), to designing, sequencing and implementing the reforms, and monitoring progress achieved. The chart below summarizes the approach.

A key stage, before sequencing and implementation begins, is for officials to consider more fully the underlying causes of the PEFA findings as well as the political, institutional and capacity constraints to reform. Understanding and ownership of these issues is a prerequisite for the successful implementation of any reform initiative.

The approach has been pilot tested by the PEFA Secretariat in three countries – Peru, West Bank and Gaza and Fiji. Each pilot was experimental and took a different form (e.g., in Peru it focused on two subnational governments). The end product of the pilots would be a PFM reform action plan. The Secretariat’s role was to facilitate the development of these plans based on each country’s own priorities and capacities.

The experience with the piloting highlighted a number of lessons:

- Ideally, government officials engaged in the exercise should be familiar with the PEFA framework, have been involved in the preparation of previous PEFA assessments or other PFM diagnostic reports, and be familiar with the findings of these assessments.

- In West Bank and Gaza, the mission focused on supporting the government in the mid-term review of their PFM reform strategy. A workshop organized by the Secretariat was followed by a series of individual, semi-structured interviews with internal and external stakeholders focusing on various aspects of PFM, and an analysis of the priorities and constraints.

- In Fiji, an initial meeting of government stakeholders was followed by short and focused working meetings with relevant departments and units. Each unit prepared their own reform plan which were then discussed in a plenary session of all central agency units.

- Engagement, participation and fresh thinking are key to success. A senior official in Fiji commented that “the main difference (with the development of the current plan) is the level of engagement. We now see that the people who are responsible for implementing the reforms are the ones who are identifying and prioritizing the reform actions”.

A key element of the guidance is that government ownership and drive is at least as important as adapting good PFM practices to local circumstances. During the pilots, longstanding advisors and partners were encouraged to limit their involvement in the meetings to create space for the authorities to set their own agenda for reform priorities and capacity development needs.

The pilots demonstrated that government ownership of the reform agenda, and the frank acknowledgement of potential constraints, are key to preparing realistic PFM reform plans. Nevertheless, the new approach has limitations. For example, the PEFA framework does not assess human capacity, legal frameworks or ICT capacities. And it does not provide any direct insights into political economy factors that can hugely affect the implementation of PFM reforms. The guidance provided in Volume IV shows how these issues can be included in the design of a reform program.

The guidance also recognizes that the sheer comprehensiveness of the PEFA framework - with 7 pillars, 31 indicators and 94 dimensions spanning the full PFM cycle - carries the risk of encouraging reform plans that are unrealistically large and cover all aspects of the budget cycle. Countries take insufficient account of priorities, timescale and resources, as well as institutional issues and constraints. PFM reform programs need to be tailored to country capacities. For many countries, it would be far better to focus on a smaller number of initiatives than to create overly ambitious improvement plans designed to meet development partner ambitions rather than the countries’ immediate needs. The guidance therefore encourages officials and development partners to be more realistic in their PFM reform ambitions.

Volume IV of the PEFA Handbook and the companion brochure remain work in progress and the PEFA Secretariat welcomes all comments and suggestions for improvement from the PFM community (services@pefa.org).

[1] PEFA Secretariat.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.