Posted by Moritz Piatti- Fünfkirchen[1]

At their core, FMIS systems enable the efficient processing of financial transactions and embed a set of controls to ensure that the budget is implemented as planned and effectively controlled. They also support the implementation of fiscal rules and provides the basis for holding the executive accountable for its budgetary and fiscal decisions. Yet, effective utilization of FMIS systems is rarely assessed. This leaves important questions such as ‘can we trust FMIS expenditure reporting?’ and ‘how effective is the FMIS system in controlling expenditures?’ unanswered.

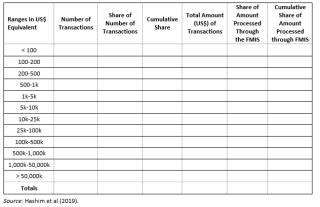

A recent World Bank Policy Research Paper[2] pursues this challenge. The authors developed a methodology to assess how FMIS systems are used by a detailed analysis of actual government expenditure transactions. Each transaction in the FMIS originates from a spending unit and must be executed against the full chart of accounts, specify the amount to be paid, the payee and his recipient account number, and the date of each transaction. From this, the authors developed an expenditure profile based on the number and volume of transactions by populating a matrix as shown in Table 1. This analysis shows how all government expenditure transactions are distributed by size. The authors also benchmarked the total volume of transactions through the FMIS against the budget as an indication of total system use.

Table 1. Sample Template for Developing the Transaction Profile (Click on the table for an improved image quality)

This methodology was applied at the federal level in Pakistan and in Cambodia, which revealed two very different challenges. In Pakistan there is very low budget coverage: almost 90% of expenditure transactions were not subject to budgetary control through the FMIS. Additionally, 40% of non-salary transactions processed by the system are of low value (< US$ 75) and make up only 0.4% of all non-salary related expenditures. Conversely, high-value transactions (> US$ 3,500) represent only 3.7% - 5% of transactions but make up more than 85% of the amount processed through the system. Nevertheless, both high-value and low-value transactions are subject to the same onerous approval process which involves a pre-audit of the transactions. This results in delays in payment processing.

In Cambodia, most of the budget is routed through the system and aggregate budget controls apply. However, very large advances are paid through commercial bank accounts held by spending units. These accounts are subsequently drawn upon but outside the system. This was confirmed by analyzing the transaction profile of the advances. Advances were found to make up as much as 90% of the non-wage recurrent budget. Some of the petty cash advances were very large—US$ 100,000 or more. These large transactions constitute the bulk of total withdrawals. Since the expenditure is allocated only at the time the advance is settled, the expenditure reports from the FMIS do not reflect the full expenditure at the program or project level.

Following this analysis, the Government of Pakistan is now considering eliminating the pre-audit process for low-value transactions. In some countries (see separate blog post on digital money) spending units requiring access to small amounts of money have been given purchase cards with limits on the amount that can be spent on individual transactions and in total. The purchase cards transactions are recorded ex-post in the general ledger. The feasibility of introducing such methods could be explored further, especially for the delivery of health and education services.

Given institutional capacities in these two countries, the use of instruments like advances often cannot be totally avoided. One improvement could be for Ministry of Finance to establish a threshold size for petty cash usage. In addition, it should be ensured that advances are settled promptly. It would also be necessary to investigate the reasons for the occurrence of high-value advances and modify the business processes related to the approval of regular transactions so that spending units do not find it necessary to draw on such large advances.

In both Cambodia and Pakistan, use of this methodology raises serious concerns about the effectiveness of FMIS systems for budget management. Yet, transactions level data are not routinely analyzed. Without such a granular assessment it may not be possible to concretely pinpoint deficiencies in coverage and utilization.

[1] Senior Economist, World Bank Group.

[2] Ali Hashim; Piatti-Fünfkirchen, Moritz; Cole, Winston; Naqvi, Ammar; Minallah, Akmal; Prathna, Maun; and So, Sokbunthoeun. 2019. The Use of Data Analytics Techniques to Assess the Functioning of a Government's Financial Management Information System: An Application to Pakistan and Cambodia. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; No. WPS 8689. Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.