Posted by Julie Cooper[1]

Over the past 30 years, governments around the world have sought to improve their public financial management (PFM) framework by utilizing information technology to streamline and automate practices. Government Financial Management Information Systems, or GFMIS, constitute the suite of electronic tools used to strengthen and automate the financial management processes used by the government. The automated functionality of GFMIS tools helps governments generate more accurate, reliable, and timely financial information, thus directly contributing to improvements in accountability, transparency, and combating corruption.

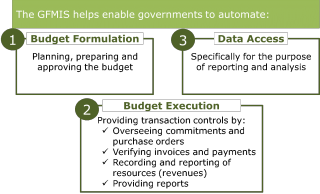

Yet when GFMIS applications are implemented in the presence of inefficient PFM practices and weak controls, only limited, if any, advancement can be expected in improving accountability and transparency. GFMIS provides the ability for government to automate the full range of PFM processes – such as budget formulation and execution, financial reporting, monitoring and evaluation, and internal control. It is a tool that can be used in parallel with, and in support of, the modernization of underlying PFM practices to improve the government’s capacity to manage its public finances (see chart below).

As an example of where GFMIS has been used successfully, take Afghanistan. Deloitte’s experience in implementing the Afghanistan Financial Management Information System (AFMIS) resulted in a reduction in variances between the approved budget and actual expenditure, the introduction of system controls to prevent or reduce corruption, and an improved allocation of resources.

An Essential Prerequisite: the PFM Diagnostic

PFM diagnostics play a critical role in identifying the underlying causes and effects of weaknesses in PFM performance. A recent study by the World Bank[2] cites examples of countries where diagnostic analysis identified a fiscal situation under stress. In the case of Honduras, Kazakhstan, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine, the causes of fiscal stress included weaknesses in legal frameworks, institutional structures, and out-of-date legacy systems used for managing government finances. These situations resulted in excessive deficits, as well as cash rationing and the accumulation of arrears.

In each of the country examples, the authors credit PFM diagnostics with improving GFMIS implementation as well as outcomes. For instance, improved fiscal control ensured that expenditures complied with budget appropriations; better cash management brought all government accounts under the treasury’s control; timely and accurate reporting improved economic management; and the preparation of statutory financial statements and improved baseline data made approved budgets more reliable and credible.

In contrast, countries such as Ghana and Zambia that had not undertaken a detailed PFM diagnostic exposed their reform efforts to serious limitations. For example:

- Not establishing a Treasury Single Account (TSA) affected cash-flow transparency and understanding of the government’s financial position;

- Adopting a “black-box” approach to implementation failed to identify priorities for implementing core budget execution processes; and

- Some countries embarked on advanced PFM reforms, e.g., performance budgeting, without first addressing basic budget preparation and execution processes.

In these cases, the World Bank study found that implementation of a GFMIS did not lead to desired improvements in budget management and expenditure control.

The Three Elements of a PFM Diagnostic

A well-designed PFM diagnostic consists of three dimensions: an examination of leadership, the application of the appropriate technology, and an assessment of the gaps in the PFM framework. Understanding the commitment of political leaders, the potential for cultural shifts within an organization, and the desired levels of accountability (both internal and external) are critical. A PFM diagnostic should also include an examination of system controls and how they interact with key PFM processes. This includes an exploration of the functionalities of the desired GFMIS and assists with the identification of the appropriate technology. Finally, to identify appropriate technical solutions, a PFM diagnostic should examine potential gaps and inconsistencies in key business processes.

To conclude, GFMIS is a powerful tool for improving accountability, transparency and to combat corruption, but deployment of such systems is not enough. Weak institutional commitment and the lack of political support for reforming PFM practices undermines the ability of governments to generate timely and reliable financial information and reduces the likelihood of successful GFMIS implementation. Reluctance to amend laws and regulations that support PFM, or insistence on retaining manual financial controls and paper-based or legacy processes, greatly impair the implementation of system-imposed controls and security and lessen the impact of streamlined or automated processes.

Note: This article is based on a presentation given by Deloitte at the 32nd Annual Training Conference of the International Consortium of Government Financial Managers (ICGFM), held in Miami, Florida, USA, May 2018. The entire presentation can be viewed here

[1] Julie Cooper is a Specialist Leader in Deloitte Consulting’s US International Development Public Finance Practice and currently PFM Team Lead for the USAID-funded Jordan Fiscal Reform and Public Financial Management project.

[2] Ali Hashim, and Moritz Piatti-Funfkirchen. 2018. “Lessons from Reforming Financial Management Information Systems”. World Bank, Independent Evaluation Office.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.