Posted by Jean Pierre Nguenang

There is an ongoing debate in public financial management (PFM) circles about how to design and implement PFM reforms in low-income countries (LICs). Critics argue that two decades of reforms have failed to produce the intended changes and that the institutional frameworks for implementing PFM reforms have been inadequate. Contributing to this ongoing debate, Mr. Ephrem Makiadi, recently published a book in French entitled “Gouverner les réformes de la gestion des finances publiques” or “Governing PFM reforms.”

The target audiences for this concise and comprehensive book are officials in Ministries of Finance (MoF) and PFM reform units in fragile states. This book discusses the key components reformers need to consider when designing and implementing a PFM reform strategy and action plan. These components include: diagnostic assessments, prioritization and sequencing of PFM reforms, technical assistance, supporting units for monitoring and implementation of PFM reforms, and communicating strategy for reforms.

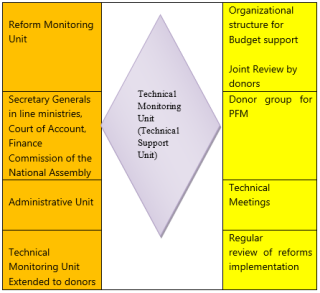

Many components highlighted in the book are well known to PFM specialists. Nevertheless the book makes a novel contribution by presenting a new approach to supporting the design and implementation of PFM reforms in fragile states (see Figure 1). This approach consists of adopting a project management method, similar to that used in implementing infrastructure projects, in order to implement PFM reforms. Moreover, the author highlights the importance of coordinating committees and meetings among the various stakeholders to help resolve overarching issues.

Figure 1: New Approach to PFM Reform Design and Implementation

Source: “Gouverner les réformes de la gestion des finances publiques” or “Governing PFM reforms”

Other interesting aspects of the book include:

- The book highlights the importance of developing supporting units for PFM reforms. The author favors an organizational structure comprising a PFM monitoring unit at the top supported by a technical unit. This is especially important in contexts where there is institutional instability, as is the case in most fragile states. The author believes that this structure provides clarity on different responsibilities and thus could help reduce conflicts.

- The book notes that technical assistance (TA) should be guided by countrys' needs, as reflected in the country’s PFM reform strategy, rather than by donors’ agenda. In the same vein, TA should be tailored to country situations rather than replicating what is done elsewhere. The book also discusses where within government to place responsibility for TA. It suggests either at the PFM technical unit or in operational units (e.g., Directorates) in accordance with the objective assigned to each TA.

- The book also highlights that the absence of a diagnostic tool for assessing the management of wages is an important gap as wages represent a sizeable share of total expenditure in most fragile states.

The book is comprehensive, however there are some gaps in its analysis especially in relation to the challenges countries face in designing and implementing a PFM strategy and its corresponding action plan.

- First, the book does not explain how to address resistance to reforms, which is common in most fragile states. Reforms always have winners and losers. The latter tend to resist reform which often contributes to failure in reform implementation. This challenge relates to overarching issues of political economy which are not extensively addressed in the book. The author does suggest that donors carry out a study of a country’s political economy. However, he does not explain how this study’s findings would be used and integrated into approaches for designing and implementing PFM reforms. To help implement PFM reforms, which are often complex and troublesome for fragile states, there needs to be a strategy for managing the process of change.

- Second, prioritization and sequencing of PFM is not sufficiently developed in this book. Based on a problem-driven approach, the author suggests the need to start with reforms that provide a visible and immediate impact with the view to creating traction. Consistent with that approach, the author also mentions the platform approach to designing PFM reforms, starting with the basic PFM reforms or easy-to-implement reforms, before moving to more advanced and complex reforms. The pros and cons of the problem-driven and platform approaches are not adequately discussed in the book, despite the extensive PFM literature on this topic.[1] At the same time, there is a need to build a consensus about what are easy-to-implement reforms, which could differ from one country to another and needs to take account of history, culture, as well as local capabilities.

- Third, country examples used in the book are limited to only two countries, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Togo, despite the latter not being explicitly cited in the book.

Finally, while this book makes an important contribution to improving PFM systems, the debate on how to design and implement PFM reforms in fragile states is ongoing and will continue in the years ahead.

If you want to know more, visit the link: http://www.editions-ue.com.

[1] M. Andrews. 2013. The Limits of Institutional Reform in Development: Changing Rules for Realistic Solutions. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.