Posted by Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster1

For more than a quarter of a century there has been a phony war raging between those in favour of public ownership of commercial assets and those against: privatisation versus nationalisation. This polarised and binary debate has missed the point. What matters is not so much who owns the assets but the quality of asset management.

For any ownership mode, be it private, public, mutual or cooperative, there is a very wide range of alternative management models/styles and the choices made from those alternatives will have a major impact on the value the asset delivers. Huge portfolios remain in government hands, including not only corporations but also vast swathes of real estate. In some cases, privatisation will make sense. In many others, it may be neither desirable nor feasible. The good news is that there are ways to sweat assets that remain in public hands, generating a higher rate of return on them—if governments follow a few sensible rules.

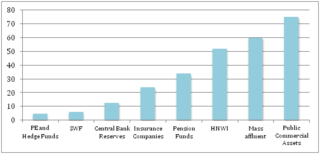

The fact that the value of most countries' public assets exceeds their public debt has been overlooked because governments seldom have a complete understanding of their portfolio. In the forthcoming book “The Public Wealth of Nations” we estimated the value of public commercial assets—not including roads (unless toll-roads), national forests or historic buildings—by piecing together work by the IMF and other organisations, and using our own assessments for the countries where no official figures are available (see Chart below). If anything, our methodology—which is described in the book—tends to underestimate asset values.2

Global Wealth Segments3 (USDtrn)

Source: PwC, World Bank and authors of “The Public Wealth of Nations”

Transparency is the key to better management. With a consolidated understanding of the value and breakdown of the portfolio of public commercial assets it would not be very difficult to improve the yield, be it of state-owned firms, real estate, productive forests or other public assets that provide some kind of income stream.

The lack of efficiency and financial return among public commercial assets is confirmed in a wide variety of case studies ranging from Francis Fukuyama's penetrating exposé of management of state owned forests in the US to the Lithuanian government's discovery that its own forestry service was 30 times less efficient than even state-owned foreign competitors.4

Missed opportunities are also an important part of the cost of public mismanagement. For example, the fracking revolution in the US, which has made it self-sufficient in oil and boosted the economy, took place almost exclusively on privately owned land. This is despite the fact that the federal government is the biggest landowner in the US, owning more than one-fifth of all land in the country.

Privatization is often seen as the only alternative, but in many cases it may not be politically feasible and often contains its own challenges including pressures to sell state assets with a heavy discount to satisfy vested interests. On the other hand, if the state remains an owner, a government has to regulate itself and there are not many good examples of self-regulated businesses.

Instead, if state assets were professionally managed, the US would be able to lower total tax receipts of the General Government by almost four per cent for every percent in increased yield from its commercial assets. Alternatively, it could use the returns to deliver a sorely needed upgrade to U.S. infrastructure.

Such a significant improvement in yield is achievable because much public real estate and other assets are not put to beneficial use at all.

Vesting all these commercial assets in a National Wealth Fund5 (NWF) would make it possible to use the appropriate tools and framework of the private sector and bring in professional management. After all, long-term value maximization is only achieved through active ownership in the hands of professionals with operational experience, taking both the economic and financial perspectives into account in its decision-making and incentivised in the same way private sector management is.

A NWF would require a ring-fenced corporate vehicle owning all commercial assets at an arms-length distance from short-term political influence. The state maintains control over what holdings should be sold when sufficiently developed and appoints the auditors, as well as the non-executive directors responsible for the portfolio. Consolidating all commercial assets under a single entity allows the production of an integrated business plan for the assets as a whole and the introduction of transparency of the highest international standard.

International examples include the ÖIAG and BIG in Austria, Solidium and Senate Properties in Finland, and Temasek in Singapore. Temasek has earned a reputation as professional investment house and in fact has track record that would be impressive even compared to private sector competitors, reporting an average annual return of 17 percent over the 35 years since its inception.

Politicians would be more successful if they focused solely on issues concerning individual citizens and on the economy as a whole. Most governments have already outsourced the management of monetary and financial stability to independent central banks, and passed control of pension funds to professional fund managers. Finding a more efficient solution for managing our public commercial assets would be the logical next step. Doing so would improve the yield of our vast, and under productive, portfolio of public commercial assets and lay the ground for the financing and management of an enormous swathe of much needed infrastructure investments.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.

____________________

1Dag Detter is Managing Director of Whetstone, former President of Stattum, the Swedish government holding company, and a Director of the Ministry of Industry. Stefan Fölster is Director of the Reform Institute of Stockholm and Associate Professor at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

2For example, only book values are available and we excluded local and regional government assets, where the lion share of value is.

3Assets under Managment by respective client segment. Further explanation is available in The Public Wealth of Nations.

4Annual Review; Lithuanian state-owned commercial assets, 2009.

5Federal systems would probably need NWFs, at three different levels, one at the central government level, one at the state and one at the local level.