Posted by Florence Kuteesa

Since the 19th century, there has been a sustained effort to develop and disseminate professional standards and qualifications in accounting. In stark contrast, there are currently no internationally accepted standards for budget preparation. Could this absence of a professional foundation for budget preparation help explain the short lifespan of many reforms that have failed to take root in budget departments and bear fruit in the form of more credible and predictable budgets, especially in low income countries (LICs)? Is it time for the budget reformers to borrow a leaf from the accounting profession’s book?

It is of concern that national budget preparation reforms in many LICs have failed to deliver intended objectives. Budget practices continue to be based on a patchwork of traditions and procedures that have evolved slowly. There are marked disparities between the principles and practices of budgeting within countries, as well as large variations across countries. New ideas and techniques of planning and budgeting are tried but, all too frequently, are abandoned or overtaken by some other initiative making it even more difficult to build strong foundation for budgeting. Short-lived budget reforms have lead to poor outcomes and dissatisfaction among staff. The continuous search for more appropriate budgeting structures and procedures is demonstrated by recent debates among the senior budget officers’ networks, in Asia, Middle East and North Africa, and Africa.

Clearly, there is no shortage of guidelines on budgeting practices. The material includes heavy handbooks on PFM, theoretical papers by economists and political scientists, country specific case studies, and publications written by practitioners such as the IMF’s series of Technical Notes and Manuals. Some of these materials are captured in a recent Overseas Development Institute publication “A guide to public financial management literature- for practitioners in developing countries”. Numerous diagnostic studies on the effectiveness of the practices have been undertaken and recommendations submitted to facilitate efficacy in the adoption of the new or revised concepts.

This rich array of information and experience, however, has not necessarily translated into permanent improvements in a more strategic, policy-oriented approach to budget preparation or more credible budgets. By contrast, the gradual adoption of Generally Accepted Accounting Standards and International Public Sector Accounting Standards appear to have left a deeper and more lasting legacy in many countries, including some of the post-conflict countries such as Sierra Leone and Rwanda.

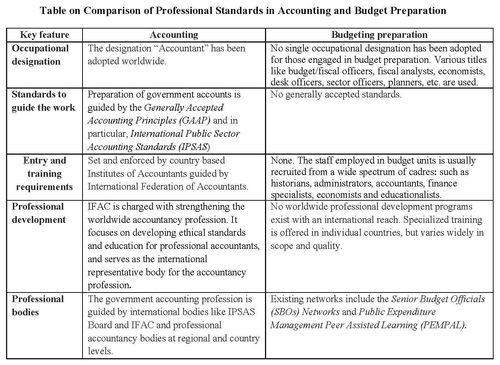

Why do accounting reforms seem to be more sustainable than budgeting reforms? One explanation could be the differences in the degree of “professionalization” between budget and accounting departments. The table below summarizes some of the main differences between professional standards in the accounting and budgeting worlds.

The lack of professional standards and career development guidelines for budget staff may explain some of the difficulties that countries face in designing, implementing, and sustaining reforms in the budget area. These weaknesses revolve around the following concerns:

- The continuously changing scope of budget preparation which attempts to address evolving needs or interests, but in turn making it difficult to embed basic budget structures and systems. In the last two decades, budget structures and systems were continually revised to address specific issues such as: integrating donor aid in the budget; introducing a multi-year perspective; and mainstreaming cross-cutting issues such as HIV/AIDS, poverty, equity and gender issues, environmental concerns; and strengthening accountability. It is important to give priority to building the basic elements of budgeting which would then provide the foundation for further advancementssuch as program and performance budgeting.

- Lack of generally accepted basic training and career development specifications have made it difficult to groom budget officers who readily understand the reform concepts, and are equipped with requisite knowledge and skills to support their implementation. In particular, finance ministries in LICs need to focus more resources on two key tasks: (i) in-depth analysis of the value-for-money of alternative spending options, and (ii) exercising an effective “challenge function” in analyzing the budget proposals of the line ministries. The development of new certification and accreditation arrangements – which already exist in related fields such as procurement and auditing – could be considered on a national or regional basis.

- Further, and most challenging, budget preparation needs to be recognized as a hybrid profession that is multi-disciplinary in nature demanding adequate understanding and skills in fields such as economic policy and development, public finance, public policy formulation, project planning and management science. In this regard, it would be useful to examine the career path of a budget officer and advise on the required professional development specifications and scope of appropriate training courses.

How can we begin to address this “professionalization gap” in budget departments? One idea would be to consider the development and dissemination of a consolidated set of generally accepted budget preparation standards, especially for LICs to use to benchmark their current practices. Networks such as the regional Senior Budget Officers’ groups and PEMPAL could collaborate with other key international agencies to examine the current vast practices that have already been documented: review existing education and training resources, forge links with colleges and training institutes, and formulate standards that could guide the professionalization of budget preparation.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.