Posted by Richard Allen[1]

The authors of this unusual and stimulating book[2] note that “tax stories from the past … can be entertaining, sometimes in a weird way, sometimes in a gruesome one, and sometimes simply because they are fascinating in themselves”. The book is long (more than 500 pages), comprehensively researched (over 1000 references) and – a pleasant throwback to the past - devoid of any charts or tables (or equations!). Its anecdotes cover the period from ancient Sumer and Rome through modern times to a look at what the future may bring. Tax policies and design as well as tax administration are covered. The book pays tribute to the path-breaking work of economists such as Malthus, Ricardo (on tax incidence), Pigou (on correcting for externalities), and Frank Ramsey (who pioneered the mathematics of tax design).

Tax history is both interesting and fun. Many of the principles of good and bad taxation run through the ages. Taxes have been shaped by wars (throughout history) and by extensions of the franchise (more recently). They have helped change the course of world events. In 1931 Mahatma Gandhi challenged the legitimacy of British rule in India by scooping a teaspoon of salty mud, boiling it in seawater and thereby producing illegal untaxed salt. The authors note that myths as well as truths perpetuate some of these stories. They explain that the Boston Tea Party, for example, was prompted by a tax reduction not a tax increase.

The book is in five parts covering: the big picture and underlying tax truths, fairness in taxation (winners and losers), tax avoidance and tax evasion, the art of tax collection (how to pluck the goose), and the messy realities of making tax policy. The authors explain how bizarre and inefficient taxes such as the window tax in 18th and 19th century Britain highlight key challenges that are at the heart of the tax design problem: “the quest for tolerable fairness, the wasteful behavioral responses that taxes induce, and the desire to administer a tax cost-effectively and non-intrusively”.

In the West, the emergence of a “stable, adequate and broadly consensual tax structure” emerged between 1889 and 1914, first in Britain followed by the US, Germany, France, and Russia. Another important innovation followed: the use of “withholding” by governments to collect taxes from companies on behalf of their employees. In the decades since World War II, however, apart from the global spread of VAT, there has been only a modest development of further broad types of tax.

The authors draw out eleven main messages from their long ride through history:

- Tax revolts (the peasants’ revolt, poll tax in Thatcher’s Britain) are rarely just about tax.

- Citizens and taxpayers should beware of the words that governments use. There are other ways to extract resources from citizens – such as borrowing or printing money (seignorage) – taxes by another name, and governments use soft language – “fees”, “levies”, and so on - to camouflage taxes.

- Surprisingly little is known about the incidence of individual taxes (the burden they impose on taxpayers) and even less about the incidence of the whole tax system.

- Fair taxation is hard to achieve, because fairness has no simple meaning, and taxation is only one weapon, and not the most important, to address issues of horizontal and vertical equity.

- The challenges of finding good measurement systems and proxies for taxation are severe – for example, the value of property is not a complete and accurate indicator of a person’s wealth or ability to pay.

- People have proved wonderfully adept at inventing new methods of avoiding and evading taxes, from the infamous tax avoidance schemes of the Vestey’s family business in the early 20th century (which revenue officials likened to “trying to squeeze a rice pudding”) to the modern day.

- The biggest cost of taxation may be invisible – the excess burden that arises when taxes alter the decisions that citizens and businesses would otherwise make.

- Taxes are not just for raising revenue – they also help correct “bads”. Pigovian taxes can make people better off even if the benefits of cleaner air and water, or uncongested streets, are not reflected in how we measure GDP. And taxes have often been used for social objectives, e.g., to encourage (or discourage) marriage and childbearing, or to reduce alcohol or drug abuse.

- Behind all the kind words of tax administrations about voluntary compliance, or of taxpayers as customers, they know that, ultimately, it is the fear of being caught and penalized that constrains evasion and keeps the money rolling in.

- Tax sovereignty is becoming a thing of the past because of globalization and the high mobility of persons, companies, and resources.

- Taxpayers should beware of mantras such as “businesses should pay their fair share of taxes” which can be dangerous by containing a kernel of truth taken too far.

Finally, the authors interestingly reflect on the possible future of taxes and tax administration. Many of these ideas sound realistic, others breach the boundaries of science fiction, as the authors admit. Tax systems will continue to be under pressure to meet the revenue raising challenges of countries’ huge debt burdens and aging populations. Greater cooperation between tax authorities will be needed, using mechanisms established by the OECD and international development agencies. The use of blockchain and other advanced digital technologies holds promise e.g., in applications to collect VAT and other revenues. Tax authorities may move away from taxing based on a single year toward taxing on a lifetime basis. The functions of collecting taxes and paying social benefits may merge, a trend that has already started in some countries. Corporation tax may change and ultimately disappear to be replaced by taxing income in the hands of underlying shareholders. Looking even further ahead genetic markers may be used that are statistically correlated with lifetime income or other measures of wellbeing or the ability to pay.

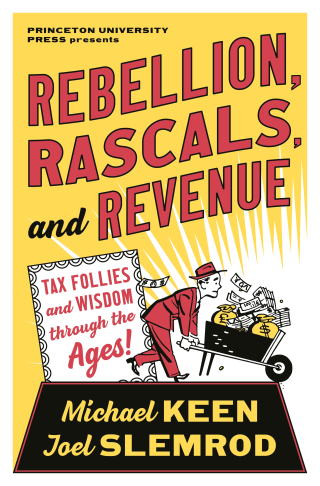

The book is aimed at several audiences which may be viewed positively or as a shortcoming. It is neither a primer on tax principles nor a history of tax but a mixture of both: a kind of crossover product that could interest both academics and more general readers who can be drawn in by the engaging stories. Some parts are clearly aimed at the more general reader, others delve into technical intricacies - for example theories of tax incidence, excess burdens, or horizontal and vertical equity - that an academic audience will appreciate but other readers may find hard going. Overall, the book is a major accomplishment (with a stunning cover) that supplements standard textbooks on tax design and tax policy and provides a lively survey and exhaustive historical analysis of these frequently dry topics.

[1] Co-Editor of the PFM Blog, and Public Finance Consultant, former staff member of the IMF and World Bank (rallen.pfm@gmail.com).

[2] This article reviews a new book by Michael Keen and Joel Slemrod called “Rebellion, Rascals, and Revenue: Tax Follies and Wisdom Through the Ages”, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2021. It is available as an audio book and a kindle version. A slightly longer version of the review was published in the academic journal “Governance” in June 2021 (Volume 34, Issue 3). See https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14680491.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.