Posted by Rahul Pathak[1]

Revenue forecasting is a critical component of budget preparation and sound management of public finances. In the last couple of decades, rising national and subnational debt burdens have been associated in many countries with substantial biases in forecasts of the fiscal deficit. An important contributing factor is the systematic overestimation of revenues, leading governments to propose higher levels of spending in the budget which are subsequently approved by the legislature. As revenue realization falls short of forecast, reining in spending has proved to be difficult in many countries. This revenue forecast bias could be a result of inaccuracies in the macroeconomic forecasting models, weak institutional capacities of the central budget office,[2] and, most importantly, a manifestation of political preferences.[3] In low and middle-income countries, these factors may assume even more significance and hinder the development of an effective PFM system.

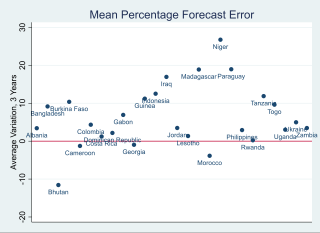

A chapter in the recently published Palgrave Handbook of Government Budget Forecasting explores the landscape of revenue forecasting in 26 low and middle-income countries with a focus on examining the presence and size of forecast bias and potential remedies.[4] Using three-year averages during 2012-17, the study finds that 85 percent of the countries (22 out of 26) tend to overestimate revenues (Figure 1). Eight countries overestimated their revenue by more than 10 percent a year, on average. The absolute forecast errors (measuring only the magnitude and not the directions of errors) are also significantly high – with an average absolute error of 8.6 percent. Over 40 percent of the countries reported a variation of more than 5 percent between the ex ante forecast and actual revenues.

Figure 1: Mean Percent Forecast Error in 26 Low- and Middle-Income Countries

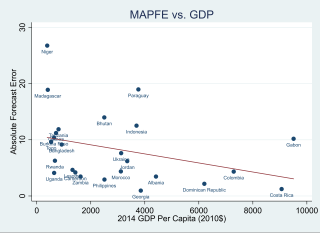

The capacity to forecast revenues accurately may depend on several technical, institutional, and contextual factors. The magnitude of forecast errors is significantly correlated with per-capita GDP – a simple proxy for institutional capacity (Figure 2). Grinyer (2019) highlights other factors such as better collaboration between the finance ministry and the tax authority which may contribute to better forecast performance. The establishment of semi-autonomous revenue authorities (SARAs) and fiscal councils, which in some countries have an explicit role in validating the government’s macro-fiscal forecasts, may also help to mitigate biases in revenue and deficit forecasts. The existing research on the effectiveness of these reforms remains inconclusive.

Figure 2: Mean Absolute Percentage Forecast Error (MAPFE) and Per-Capita GDP

Lastly, the chapter highlights the lack of research on revenue forecasting in low- and middle-income countries and identifies avenues for future research. One of the challenges in carrying out such research is the lack of easily comparable data on ex-ante revenue estimates and ex-post realizations in many countries. Keeping track of anticipated revenues and actual outcomes and identifying the causes of variance is important not only from the perspective of budget transparency and its credibility, but also to keep a check on deficit bias and increasing debt burdens.

[1] Assistant Professor of Public Finance and Budgeting, Marxe School of Public and International Affairs, Baruch College, City University of New York (CUNY). (email: rahul.pathak@baruch.cuny.edu)

[2] Battersby B. and Lautier E. (2019) Developing Macro-Fiscal Forecasting Frameworks in East Africa, IMF PFM Blog, August 22. https://blog-pfm.imf.org/pfmblog/2019/08/developing-macro-fiscal-forecasting-frameworks-in-east-africa.html

[3] Grinyer J. (2019) The Politics of Revenue Forecasting. IMF PFM Blog, February 7. https://blog-pfm.imf.org/pfmblog/2019/02/-the-politics-of-revenue-forecasting-.html

[4] Cangiano, Marco, and Rahul Pathak (2019) “Revenue Forecasting in Low-Income and Developing Countries: Biases and Potential Remedies,” in Daniel Williams and Thad Calabrese (eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Government Budget Forecasting, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.