Fiscal rules—permanent quantitative constraints on government finances—are an important tool to help mitigate the macroeconomic challenges associated with managing natural resource revenues. They can act as a commitment mechanism, binding successive governments to a long-term budgetary ceiling and helping politicians fight the urge to overspend during elections. They can also help prevent fiscal crises and encourage governments to save or pay down debt in good times so that they have fiscal space to spend during recessions.

In NRGI’s new study, we reviewed the characteristics of fiscal rules in countries assessed in the Resource Governance Index (RGI). Out of the 79 countries covered by the index, 34 have at least one fiscal rule in place. The most common types of rule are debt ceilings and various types of budget balance targets. We also analyzed the levels of compliance with these rules in 2015 and 2016, the years directly following the commodity price crash, when oil prices fell by half and mineral prices by one-third. As such, it provides new insight into how these fiscal rules performed during serious economic shocks. We found that in these two years governments adhered fully to the rules in only six countries (Figure 1). In 25 cases, governments suspended, modified or disregarded their rules. Governments breached rules in a wide range of countries, rich and poor.

Figure 1. Number of RGI countries in compliance with fiscal rules in 2015 and 2016 (Click on the figure for a better image quality)

What are the reasons for this low level of compliance with fiscal rules? First, many of the fiscal rules were not appropriately designed. Some rules (especially debt ceilings) were too easy to accommodate and made compliance trivial, while other rules proved constraining given the shock precipitated by the commodity price drop. Few governments have well-defined escape clauses to evoke when faced with a commodity price shock.

Second, a number of countries did not follow their rules in good times either, or used questionable practices to modify or disregard them. Compliance was especially weak in countries with limited or no national oversight of fiscal rules. No countries complied with supranational rules in the period reviewed.

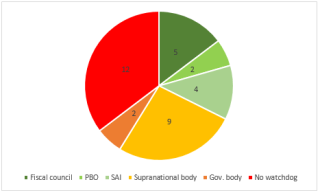

Figure 2. Oversight institutions monitoring fiscal rules compliance across RGI countries (Click on the figure for a better image quality)

Only a third of the countries have a national oversight organization (e.g., a fiscal council) monitoring observance of these rules (Figure 2). The most common are supreme audit institutions, fiscal councils, or parliamentary budget offices. These institutions vary in their level of independence and capacities, and not all of them produce reports that clearly show whether governments are observing the rules.

Countries often provide limited and technical public information on fiscal rules and whether governments are complying with them. The lack of public engagement on fiscal issues ultimately makes them easy for governments to discard. This limits the effectiveness of these long-term commitments, which governments often sacrifice in favor of short-term political gains.

Our paper makes the following recommendations, some of which - especially those regarding the oversight of fiscal rules - apply beyond just resource-rich countries:

1. Resource-producing countries without fiscal rules should consider adopting them to promote fiscal sustainability and counter-cyclical spending. They should tailor them to their resource endowments, economic situation, and the country’s governance context.

2. Fiscal rules in resource-dependent countries should generally be strongly counter-cyclical. This enables countries to avoid boom and bust cycles, and will yield rules that governments are more likely follow. In these countries, governments should avoid simplistic overall budget balance rules, or only setting a debt ceiling as a percentage of GDP. Expenditure rules, the non-resource balance, or structural balance rules are generally more suitable, and targets should be set in absolute numbers or as a percentage of non-resource GDP.

3. Fiscal rules should be simple to calculate and easy to monitor and enforce, especially in countries where there is no established oversight actor with strong technical capacity. All fiscal rules need to be supported by good PFM systems and fiscal transparency. Only countries with very strong capacity and institutional independence should use structural balance rules.

4. Governments should incorporate reasonable and well-specified escape clauses into fiscal rules. To be most useful, governments should provide specificity and operational guidance on their fiscal rules, which can otherwise become a source of ambiguity and abuse, undermine the rules’ credibility and raise questions of accountability.

5. Governments should consider adopting supranational fiscal rules into domestic law, where appropriate, and establishing domestic oversight of these rules.

6. Governments should build consensus around the adoption of a fiscal rule or the modification of an existing rule by requiring large parliamentary majorities for major changes, seeking support from multiple political parties, and engaging with the public when designing the rule.

7. Soft penalties that require public hearings or additional reporting when rules are violated may be useful for encouraging compliance. Harsher penalties may be appropriate for attempting to circumvent procedural aspects of the rule.

8. Government oversight organizations should aid in bringing accountability to public finances. They should have the independence, legal mandate and resources they need to monitor compliance with the fiscal rules. Attaching such an entity to the parliament might be a fruitful avenue in countries with low capacity but a strong parliamentary tradition, rather than establishing new institutions.

9. To be effective, fiscal rules need awareness and oversight from followers of public policy. Governments should inform citizens about the rules through the budgetary process. The media, parliament, civil society organizations, think tanks, financial sector institutions, and credit rating agencies should also play a role in monitoring the rules.

10. The international community and economists/experts should do more to inform stakeholders as to why counter-cyclical and sustainable fiscal policy is key to growth and diversification. More effort should go into supporting implementation rather than codifying new fiscal rules.

[1] David Mihalyi is a Senior Economic Analyst at the National Resource Governance Institute, London, and Visiting Research Fellow at the Central European University, Hungary (dmihalyi@resourcegovernance.org).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.