Posted by David Gentry[1]

A major effort in PFM in the last few decades has been to extend the time horizon of the budget. While there are many variations of a medium-term budget framework (MTBF), and much discussion about the various benefits of each variation, one benefit is common to all. That is, to show more fully the financial consequences of decisions made today. This is often called a baseline.

Like MTBFs, there is no precise definition of a baseline. Most countries publish a medium-term fiscal forecast, comprising a single baseline or baseline scenarios to illustrate uncertainty. In addition, many countries are now publishing baselines for major recurrent programs, some publishing program expenditure forecasts of up to 10 years. Because baselines are inherently policy based, they are not calculated for ministries or other organizational units without regard to the policies they implement.

The period covered by a baseline is determined by the nature of what is being forecast. Some decisions have short lags between the decision and realization of the full cost of that decision. For example, purchasing a vehicle and the cost of operating and maintaining it. Other decisions have a very long lag between the decision and the full cost of it. Defined benefit pension plans are an obvious example, in which employees today are promised benefits that will not be paid out until decades into the future. In the case of pensions, it is common to forecast baselines at least 20 years into the future, with some countries publishing projections covering 50 or more years (for example, the United States forecasts social security revenues and expenditures 75 years into the future).

Future costs are often higher than what might be presented at the time of the decision. Indeed, arguably this is the single most important reason for developing baselines. Therefore, the policy response to estimating medium- or long-term costs is frequently to want to reduce the baseline, or to bend the trend line downward. Debt levels and public pension schemes are common areas of focus to ensure the sustainability of long-term cost trends, and to take steps to get these trends under control if they are not sustainable.

Bending a baseline downward often does not mean that costs become lower in nominal or real terms – rather that costs rise less rapidly than would otherwise occur. These are often called “savings”. Success can be declared when reducing cost increases from, say, 5 percent annually to 3 percent annually. Over many years, this cost reduction is significant.

Public debate on shifting baselines downward often gets bogged down in confusion over terminology. Claims of savings are often ridiculed by those opposed to them, who argue that the savings are not real because costs are still going up. Public debate would be aided if there were a concept and term to indicate that such savings are in comparison to a baseline, and are not savings in the common sense of the word. In fact, there is something comparable: that is, opportunity cost. Is it time for a concept of “opportunity savings”?

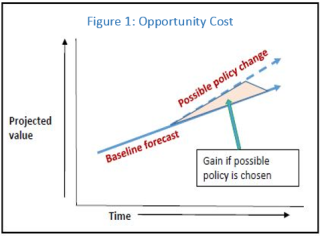

There are many similarities between opportunity costs and opportunity savings. Figures 1 and 2 illustrate this argument. “Opportunity” is what could occur and is measured as the difference between a baseline and the possible policy change. The adjective “cost” indicates gains foregone if a change from the baseline were not adopted. Gains could be viewed as additional revenue or savings. Therefore, one could argue that the term opportunity cost could apply to both revenue and savings foregone.

But discussions about gains and savings occur in different contexts. Discussions about opportunity costs usually have a positive focus on increasing revenue or benefits. While better use of resources might mean shifting resources from one project or one constituency to another, and thus is effectively a cutback to the losing project or constituency, the tone of the public debate is on more effective use of resources. It might also refer to increasing resources. Rarely does it imply reducing resources or inputs.

Discussions about opportunity savings typically imply cutbacks in resources. The focus is often on increasing efficiency and reducing the quantity of benefits rather than on effectiveness. The shifting of resources is often between government program and taxpayers, rather than between alternative government programs.

It is difficult to say definitively that a new term is necessary. The test is whether a new term would foster more rational discussions of bending the long-term costs trend downward. Such discussions are going to occur more frequently as baselines increasingly are adopted analytically and extend further into the future. Every time I hear in public debates “how can there be savings when costs are going up?”, the more I think a new term would be useful.

[1] Senior Economist, PFM Division 2, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.