Posted by Murray Petrie[1]

Direct engagement between citizens and governments is increasingly recognized as a critical link in the chain between fiscal transparency, more effective accountability for public financial management, and better fiscal and development outcomes. The importance attached to public participation reflects the acceptance that citizens and civil society organisations are important agents of good governance and sustainable development, alongside markets and the state.

So, what is public participation in fiscal policy?

Public participation refers to the variety of ways in which the public – including citizens, civil society organizations, community groups, business organizations, academics, and other non-state actors – interact directly with public authorities on fiscal policy design and implementation. The interactions range from one-off consultation, through face to face deliberation, to ongoing and institutionalized relationships.

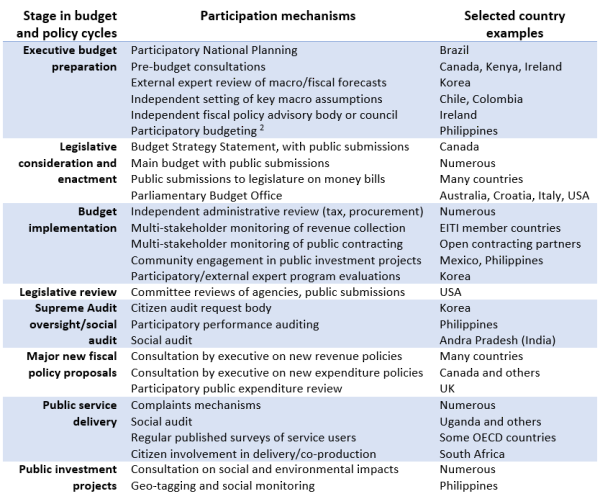

Public participation covers both macro-fiscal policy – the main fiscal aggregates, the appropriate size of the deficit and so on – as well as micro-fiscal issues of tax design and administration, and the allocation and effectiveness of spending. It encompasses engagement in four main domains:

- Across the whole annual budget cycle, from budget preparation, legislative approval, budget implementation, to review and audit.

- Related to new policy initiatives or reviews (for example, of revenues or expenditures) that extend over a longer period than the window for preparation of the annual budget.

- In the design, production and delivery of public goods and services.

- In the planning, appraisal, and implementation of public investment projects.

To make the right to public participation more practical and meaningful, the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT) has implemented a multi-year work program to generate greater knowledge about country practices and innovations in citizen engagement. Outputs include country case studies, a set of Principles of Public Participation in Fiscal Policy, a Guide on Public Participation, and instruments to measure public participation in fiscal policy.

The table below sets out selected examples of public participation in fiscal policy, to illustrate the broad range of mechanisms. Details of many of these mechanisms are available in the GIFT Participation Guide.

Table: Examples of Public Participation in National Fiscal Policy

[1] There are many examples of participatory budgeting at sub-national level, pioneered in Brazil.

Where did the recent push for increased public participation in fiscal policy come from?

Requirements for public participation are incorporated in:

- Principle 10 of the 2012 GIFT High Level Principles on Fiscal Transparency, Participation, and Accountability stated that: ‘Citizens and non-state actors should have the right and effective opportunities to participate directly in public debate and discussion over the design and implementation of fiscal policies.’

- The Open Government Partnership.

- The 2014 IMF Fiscal Transparency Code (Principle 2.3.3).

- The OECD’s Principles of Budgetary Governance 2014 (Principle 5).

- Some PEFA indicators (e.g. PI-18.2 on legislative review of the budget)[3].

- The Sustainable Development Goals, including Goal 5 (gender equality), Goal 10 (reducing inequality), and Goal 16 (peace, justice and inclusive institutions).

- The forthcoming OECD-GIFT G20 Budget Transparency Toolkit (Section 4, Openness and Civic Engagement).

- The 2017 Open Budget Survey includes an expanded section on public participation by the executive, the legislature, and the Supreme Audit Institution.

Possible objections to increased public participation in fiscal policy, and responses

- Public participation is costly: but the ICT revolution has dramatically cut the cost of direct engagement with citizens, and created completely new possibilities for interaction.

- Direct public engagement could undermine the role of existing decision making and accountability structures: but public participation is designed to add to, complement, and strengthen existing governance arrangements - and increase trust in government - not to set up parallel processes.

- Budgeting requires budget secrecy: but policy making in general has become much more open, and budget secrecy can be retained where warranted.

- Public engagement could slow down the policymaking process: but it can also help improve policy quality and legitimacy, avoid policy reversals, and thereby save time and cost.

Where to next?

Direct public participation has emerged as an important new international norm on how governments, legislatures, and supreme audit institutions should manage and oversee public resources. GIFT will continue to support the implementation of this norm through deepening the Guide on Public Participation, and gathering more evidence on and supporting assessments of country practices and their impact. We would be pleased to receive additional country examples of effective public engagement for inclusion in the Guide – and in fact we are offering prizes for compelling stories of viable approaches to public engagement in central government fiscal policy submitted by 25 August 2017 (see http://www.fiscaltransparency.net/giftaward/).

[1] Murray Petrie is Lead Technical Advisor for the Global Initiative on Fiscal Transparency (GIFT), based in Washington DC (petrie@fiscaltransparency.net). A longer version of the present article appears on the GIFT website.

[2] There are many examples of participatory budgeting at sub-national level, pioneered in Brazil.

[3] In addition, GIFT has developed an indicator measuring public participation in fiscal policy that is being piloted as a voluntary supplement to a PEFA assessment.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.