Posted by Verena Fritz, Marijn Verhoeven and Stephanie Sweet

Reforms of public financial management (PFM) systems – pursued by many countries and supported by development partners -- have attracted considerable debate and analysis in recent years. Significant variation in progress achieved and lack of broad-based and sustained improvements in metrics of PFM performance, as reflected in the World Bank’s CPIA ratings and PEFA scores, suggests to many observers that outcomes have not matched reform efforts and expectations.

This has led to a search for better solutions in two directions: first, grounding reform efforts in stronger problem analysis, and based on this, a better fit and sequencing of reform approaches to specific country circumstances and identified bottlenecks. Second, seeking a better understanding of non-technical aspects and, in particular, the role of political economy drivers in influencing which PFM reforms are pursued, in which countries, and with what degree of success. ‘Doing things differently’ along these lines sounds promising, but reformers and development partners may well question whether we know enough to pursue such alternative approaches on a wider scale.

At this juncture, it is important to understand more systematically how reform success has varied across countries and components of PFM reforms, and over time. In a new working paper on the Drivers and Effects of PFM Reforms, we explore these issues. Such an exploration has only recently become possible due to the availability of cross-country and time series data about PFM systems based on PEFA assessments (and the less granular CPIA ratings). These data are now available for 144 countries and a time period of about ten years. The paper builds on initial efforts in this direction carried out by de Renzio et al. (2011) for the Overseas Development Institute and by Matt Andrews of Harvard University.

A key question we ask is in how far countries’ PFM performance is determined by country conditions, and if so, which of these factors are most significant – such as the level of GDP, the recent growth trajectory, political-institutional stability, or other conditions, such as the population size or the degree of natural resource dependence.

A glass half full

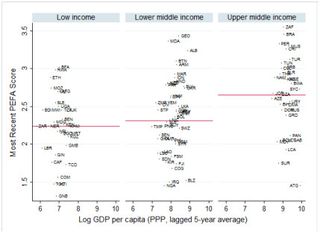

It is interesting to see that (only) about half of the variation in the status of PFM systems can be explained by the total basket of country conditions considered, including macro-social, economic, and political factors, such as the income level, current political stability, population size, and the degree of natural resource dependency. Among these factors, the level of GDP seems to be important, as expected, and recent growth makes a significant but small difference. As shown in the figure below, for each of the three income groups considered – low, lower middle, and upper middle income – there is a wide dispersion in terms of recent PFM performance, around an average PEFA score for each group (on a range of 1 – 4) that is about 0.5 points higher for the highest income group than the lowest. The relatively weightiest factors, however, are natural resource dependence and being a small island state (both negative) and having programmatic political parties (positive).[1]

Regarding the influence of macro-political variables, the paper offers some interesting insights. Across the board, ratings for budget accountability – i.e., the summary of indicators for external audit and parliamentary oversight – are lower than those for other PFM dimensions (budget preparation and execution). This holds true across all three income groups, indicating the challenges that many countries face in strengthening this area of PFM, which could be related to lower effort by governments as well as possibly by development partners. Moreover, the paper finds that whether a country has a more democratic or more autocratic regime does not seem to matter – either for the strength of PFM systems overall, or for developing effective budget accountability mechanisms.

The macro-political factor that does seem to matter most is whether a country has ‘programmatic parties’. This result could reflect the influence of several causal mechanisms, such as enabling a more long-term approach and continuity in reform efforts, as well as a greater interest in ‘getting something done’ beyond just staying in power, which in turn creates an incentive to have a public sector that can reliably execute policies.

Room for improvement

Interestingly, improvement in PFM quality is highly correlated with where a country starts, but with a negative sign. Thus, countries that started off with worse PFM performance show stronger improvements over time than those with already better systems at the start.

A key overall take-away is that while country circumstances are important, they remain far from fully determining what can or cannot be achieved. Specific reform approaches and efforts are likely to be important in making a difference between countries which acquire good PFM systems against the odds, or over and above average performance among those with similar conditions, while in others the opposite is true.

But does a good PFM system really matter?

The final substantive section of the paper is devoted to exploring whether stronger PFM systems are associated with better outcomes – defined as (i) aggregate fiscal discipline, (ii) less variation between budget plans and budget outturns, and (iii) better health and education outcomes relative to the fiscal resources devoted, building on methodology developed for a 2013 report on the impact of Medium Term Expenditure Frameworks. The analysis finds a generally positive relationship between the quality of PFM systems and outcomes (i) and (ii), albeit for aggregate fiscal deficits the improvement is that actual deficits are closer to planned levels, rather than being smaller as such. However, there is no clear relationship with expected outcome (iii). Since measuring efficiency in service delivery still poses many challenges, measurement problems may play a significant role in driving these results. This issue should become the focus of further work: expected results on service delivery are important for motivating decision makers to commit to PFM reforms, and to provide political backing when needed to address reform bottlenecks.

Overall, we hope the analysis can inform several policy and research questions around PFM. For us, the next step is to explore through a set of in-depth case studies how PFM reforms efforts have been initiated and sustained in particular countries, in order to better understand how political economy factors contribute to the fluctuation in reform efforts over time, and what might be done differently to sustain reform efforts. PFM Blog readers’ suggestions about interesting reform experiences and ‘turns’ are very welcome!

[1] As defined by Phil Keefer, Parties are ‘institutionalized’, i.e. ‘programmatic’, if they can maintain the party’s reputation for favoring a particular policy program, facilitating the election of party candidates; or if they oblige leaders and members to systematically pursue the collective economic interests of party members. This contrasts with clientelistic and personalistic parties which are vehicles created by networks of individuals to seek access to power, but which do not have a clear and sustained policy platform. See Keefer (2011).

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.