When the financial crisis broke out in 2008, many governments were caught off guard. In many cases fiscal risks had not been correctly assessed, leaving unexpected and unprecedented gaps in public finances. This in turn led to the adjustment and austerity measures which are still being felt today. According to the IMF’s own calculations, almost a quarter of the unexpected increases in government debt after the crisis were due to “incomplete information about the government’s underlying fiscal position”. In other words, serious gaps in fiscal transparency were at least partly to blame, and these were often related to particular areas of public finances that are kept hidden from public view. This includes activities that are not captured in the regular budget system and the reports generated throughout the annual budget cycle. Quasi-fiscal activities carried out by public corporations and extra-budgetary spending figure prominently among such activities.

The Open Budget Survey, produced every two years by the International Budget Partnership, consistently finds that many governments do not include sufficient information on these and other similar activities – e.g. tax expenditures, contingent liabilities, etc. – in their budget documents. This lack of information has led us to name these activities the “hidden corners” of public finance, and is the subject of a recently completed project based on two years of research and a number of country case studies. Governments may use these “hidden corners” to keep citizens, the media and oversight institutions from having a full picture of a country’s public resources – with some of the disastrous consequences seen after the crisis.

Publishing timely and comprehensive budget documents, as a consequence, may not be enough to ensure full transparency and accountability. Take the case of Russia, for example. The Russian government scored among the top ten countries in the 2012 Open Budget Index, and has committed to further improving its performance. At the same time, according to a recent IMF report, a large (and growing) share of public spending is kept off-budget, and fiscal reports do not fully account for the activities of a large and complex array of government-controlled enterprises.

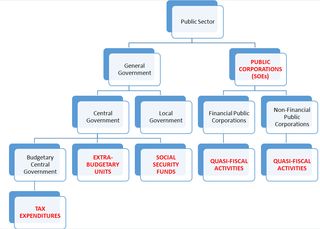

The synthesis report and case studies are aimed at better understanding the issues linked to transparency and accountability in some of these “hidden corners”(see the figure below). Many of the issues and challenges uncovered in the studies relate to areas of public finance that involve large shares of public resources, but that are often marred by weak government controls and lack of transparency, or for which accountability mechanisms are different and separate from the ones that apply to the regular budget process. Eight country case studies were commissioned from country-based experts. Practices investigated ranged from state-owned enterprises, quasi-fiscal activities, extra-budgetary funds, to tax expenditures. We were especially interested in the challenges that organizations interested in monitoring these types of government activities might face.

Figure. The public sector, its components, and the “hidden corners”

The case studies reveal a wide variety of country circumstances and approaches. In a number of cases it is possible, by looking beyond the key budget documents that the Open Budget Survey focuses on, to gather extensive amounts of information on these areas. Many of the governments studied approve laws and publish reports that allow a reasonably detailed picture of government-funded activities and operations beyond the core budget to emerge. These take the form of annual reports published by state-owned enterprises, special appropriation laws for extra-budgetary funds, and tax expenditure reports, among others. Some areas, such as quasi-fiscal activities, remain more difficult to detect and monitor, and some extra-budgetary institutions are still not reported on in any detail.

It is important to note that the case study countries were partly selected because of their good levels of basic budget transparency, and in light of their interesting approaches and experiences in some of the areas covered. In most countries in the world, normal practices around reporting and publishing information on EBFs and SOEs, for example, will be much worse than those described in the synthesis report and covered in more detail in the country case studies.

Some broad cross-cutting issues regarding some of the factors that may have led governments disclosing information on these categories also emerge from the studies. Domestic factors, such as democratization processes and pressure from oversight institutions and civil society groups, were predominant, but international influences, including those from regional economic agreements (e.g., the EU), international capital markets, and international organizations also helped shape government responses and improve transparency practices.

Civil society groups and other actors interested in monitoring government activities and operations in these areas can use the report and the case studies as a resource to gain a better understanding of some of the issues involved, some of the innovative practices that exist around the world, and some of the key topics that they should look into if they decide to investigate any of the areas above in further detail in their own countries.

[i] Paolo de Renzio is Senior Research Fellow at the International Budget Partnership. The main author of the synthesis report for this project was Murray Petrie, Director of ESG, a consultancy firm in Wellington, New Zealand.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.