Posted by Tim Irwin

It is common to assume that people are risk-averse—that they are willing to accept a risk only if it brings the reward of a greater expected return. But psychologists have found that people are sometimes risk-seeking—that they are willing to pay to assume a risk. Such behavior creates a problem for the management of fiscal risk, since it involves the government’s paying an expected cost and increasing its exposure to risk. So it’s worth thinking about when governments might be vulnerable to risk-seeking behavior.

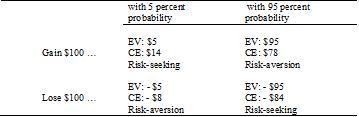

According to the psychologists’ research, there are circumstances in which we conform to the assumption of risk-aversion. One is when we are faced with a high probability of winning something. Specifically, an experiment found that, on average, people considered that a 95 percent chance of winning $100, which has an expected value of $95 (the prize times the probability), was worth only $78 (see table). We also tend to be risk-averse when faced with a small probability of a loss. We might be willing, for example, to pay an insurance premium of $8 to avoid a 5 percent chance of losing $100, which has an expected cost of only $5.

Risk-aversion and Risk-seeking: Expected Values (EV) and Median Certainty Equivalents (CE) in One Study of Four Bets

Source: Amos Tversky and Craig A. Fox, “Weighing Risk and Uncertainty”, Psychological Review 102(2), 1995, pp 269–283, reprinted as ch. 5 of Choices, Values, and Frames, ed. Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Yet in other cases we’re risk-seeking. We might pay as much as $14 for a 5 percent chance of winning $100. We also tend to be risk-seeking when our choice is between a sure loss and a gamble that offers a substantial probability of a larger loss. We may prefer a 95 percent chance of losing $100 to certain loss of $84. In both these cases, we are willing to pay a premium to assume risk.

It’s not possible to make confident inferences about the behavior of organizations from experimental evidence about individual decisions. Organizational incentives might make managers risk-averse when they were choosing on behalf of an organization, even if they would be risk-seeking if they were choosing for themselves. But the phenomenon of risk-seeking in the face of probable losses gives rise to concerns.

For one thing, it adds weight to fears that guarantees may be preferred to cash subsidies even when the latter are more appropriate. The main appeal of guarantees is usually that they do not have an immediate budgetary cost. But spending managers faced with probable losses might favor guarantees even if their expected cost had the same weight in budgeting as a certain cost of the same amount.

For another, when faced with looming losses, the managers of troubled banks or public enterprises might be attracted to taking risky bets with negative net present value. If the bank or enterprise is implicitly or explicitly government guaranteed, that creates a problem for the government. The possibility of risk-seeking in the face of losses therefore adds weight to recommendations that ministries of finance should be quick to intervene to monitor and control the risk-taking of troubled institutions with government guarantees.[1]

[1] Traditional financial theory supports the same recommendation. Given the nature of shareholders’ option-like claims on the assets of a company, the shareholders of a company with little equity may have strong incentives to take on risk to transfer value from lenders or guarantors to themselves. See, e.g., Robert C. Merton and Zvi Bodie, “On the Management of Financial Guarantees”, Financial Management, Winter, 1992.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.