Posted by Zsuzsanna Lonti and Natalia Nolan Flecha

Avoiding a global economic depression hasn’t come cheap. Although many people would agree the stimulus measures have been—for the most part—necessary and effective, many governments in OECD countries are now left with hefty bills, and they are now working to balance debt reduction without harming prospects for growth. As a result, many OECD governments are under pressure to demonstrate that they are up to the job of tackling these and other mounting challenges, while at the same time implementing austerity measures. Governments must prove they have learned from the crisis, to show that is has not damaged them but rather made them stronger. They must demonstrate they are capable of strategic foresight and agility, of managing risks, of forging strategic partnerships across government and beyond, and communicating better with citizens. If anything, the crisis has underscored the fact that government performance can make a difference in terms of growth, as well as in the wellbeing of citizens and their trust in government.

It’s clear governments are doing a great or a lousy job on these issues depending on which newspaper you read or TV show you watch. It’s always been like that, and why not? Democracy thrives on debate, but good governance needs facts as well as opinions. Quantifying and measuring government actions can help leaders and managers make better decisions, identify areas for reform, and hold governments accountable to citizens.

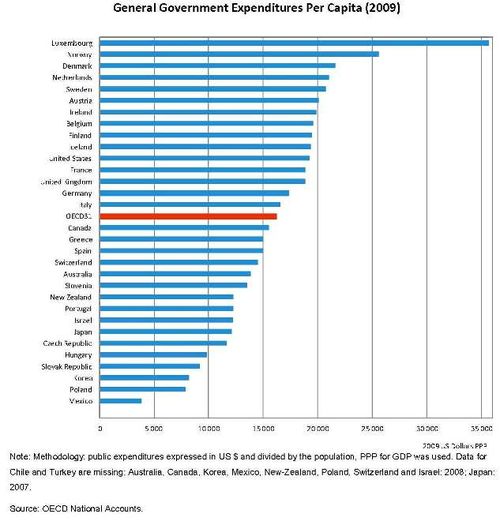

However, measurements of government performance are frequently frail, crude or simply missing at national level, but even more so for international comparisons. Many experts agree that existing comparative data on government activity are shot through with problems and weaknesses. While the measurement of public sector inputs (e.g., expenditures and employment) are the most developed and internationally standardised, they still need improvement. There are also many indicators on government processes for which the quality could be further improved, while the measurement of outputs and outcomes of public activities are still in their infancy. These are the realities of measuring government performance despite the fact that government expenditures in OECD countries constituted, on average, 46% of GDP in 2009. That’s about 16,000 per capita in the OECD (US$ PPP). Indeed, representing around half of GDP in many countries, the public, politicians, and academics alike need to understand what government is aiming to achieve and what it is actually achieving.

Enter the OECD’s Government at a Glance, a collection of key public administration indicators and part of the OECD’s contribution to evidence-based policy making. Government at a Glance aims to improve the general quality and comparability of government activity data and to enable better benchmarking between countries. It provides indicators to assess how well governments deliver public services, uphold core public values, efficiently use public funds, and provide a fertile ground for continued growth and social development. And it encourages a better OECD-wide exchange on the efficiency and effectiveness of governments.

At the level of individual countries, the publication has enabled robust benchmarking. By using common units of analysis, it has facilitated a structured practitioner dialogue, moving away from simplistic best practice approaches to a more nuanced view of the interplay between political and institutional structures, public governance and management practices, and public sector outputs and outcomes.

Government at a Glance is unique in that the indicators have been selected and/or developed in consensus with member countries; therefore, all countries are stakeholders in the programme and take the results seriously, drawing on them to shape decisions and reform agendas.

The first edition of Government at a Glance was released in 2009, in six languages, with over 30 indicators. These included data on government revenues, expenditures and employment, as well as on policies and practices in integrity, e-government, and open government. It also introduced several composite indicators summarising key aspects of human resource management, budgeting and regulatory management. This first edition has been well received and has contributed to the ongoing debate about quality governance in OECD countries.

The next edition is due out in May 2011. It will both build on the existing foundation and include new information. In particular, it will offer new data on fiscal sustainability, inequality, innovation in service delivery, public service compensation, trust in government, and key output and outcome measures from the policy sectors of education, health and tax administration. Ministers will get a preview of some initial results in November at the meeting of the OECD Public Governance Committee at Ministerial level: “Towards Recovery and Partnership with Citizens: The Call for Innovative and Open Government”.

Future editions of Government at a Glance will be able to present comparable data over time, in order to shed light on the impact of reforms on performance, and will cover even more countries, as well as expand the policy sectors and levels of government analysed.

Government at a Glance is an ongoing project, always on the search for indicators that capture the dimensions of performance that matter most. We welcome your views. Do you think there are core government capabilities that have become even more important after the crisis? If so, which ones?

Public expenditure represents around half of GDP in many OECD countries, or about 16,000 US$ PPP per capita.

Download Expenditures Per Capita

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.