Posted by Jason Harris[1]

Australia has one of the strongest fiscal positions in the developed world, with the budget projected to return to surplus in 2012, and net debt projected to peak at 6% of GDP. [2] The relative consensus between the main political parties on the long-standing medium-term fiscal strategy has played a key role in delivering these outcomes. The strong starting position ahead of the global fiscal crisis has given Australia the flexibility to engage in relatively aggressive stimulus policies, without endangering long-term sustainability.

The Australian medium-term fiscal strategy has three cornerstones:

· Achieving budget surpluses, on average, over the medium term/business cycle;

· Keeping taxation as a share of GDP on average below 23.6% of GDP, the level reached in 2007; and

· Improving the government’s net financial worth over the medium term.

The commitment to budget surplus over the business cycle has broad acceptance across the political spectrum and throughout the community. Initially the guiding principle adopted by the center-right Coalition in 1996 was to maintain budget balance over the cycle. It was tightened from balance to surplus in 2007 when the center-left Labor party came to power.

This commitment to budget surplus is one of the key factors considered by decision makers when setting up the budget envelope. All policy decisions are taken with an eye on the impact on the budget bottom line—not just for the next year, but over the forward estimates (the next 4 years). And at the end of the budget process, it is the budget envelope that takes precedence over individual policy considerations.

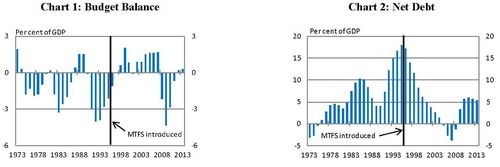

By holding to this element of the strategy, Australia has maintained a sound fiscal position over many years. The Commonwealth Budget has either been in balance or in surplus for 10 out of the 13 years since the strategy was adopted, with an average balance of +0.3% of GDP since 1996 (Chart 1).

This includes the most recent 2 years, during which the global financial crisis has wreaked havoc on budget positions across the world. Australia was no exception: the budget moved into deficit (peaking at 4.4% of GDP), as a result of the operation of the automatic stabilizers, combined with substantial discretionary fiscal stimulus.

However, in contrast to many other economies, this is projected to be only a temporary deficit, and one that lies well within the bounds of sustainable fiscal policy. A forthcoming post will examine Australia’s fiscal response to the crisis and the deficit exit strategy that outlines the path to surplus.

In the 5 years prior to the crisis, the government ran surpluses averaging 1.5% of GDP, and net debt had been reduced from a peak of 18% of GDP in 1996 to -3.8% of GDP (i.e., a net asset position) in 2007 (Chart 2).[3] This provided the government the ability to respond to the crisis swiftly, without the concerns about risking fiscal sustainability that other countries may have had to consider when calibrating their stimulus packages.

Furthermore, the medium-term fiscal strategy was flexible enough to accommodate the fiscal stimulus enacted by the government, due to the “on average, over the medium term” scope and timeframe of the target. Indeed, this was the intent of the authors when the strategy was introduced.

While reducing the year-to-year prescriptiveness of the strategy, this flexibility does increase its robustness, and ability to deal with economic shocks, without needing to temporarily put the strategy on hold, or worse, drop it altogether, as can be the fate of more prescriptive (deficit) targets in difficult situations such the global financial crisis.

The second element of the medium-term fiscal strategy, which was adopted more recently, is the commitment to keep taxation as a share of GDP, on average, below the level for 2007-08, i.e., 23.6% of GDP. Combined with the surplus target, the revenue ceiling implies a spending ceiling over the medium term. This implicit spending ceiling does (at present) only apply to the federal government.

The spending limit was introduced in 2007 by the incoming Labor government, to assure voters that the budget surpluses would be achieved through disciplined spending rather than higher taxation. The combination of the surplus on average and the tax to GDP limit effectively limits the size of federal government to less than 23.6% of GDP, the tax share in 2007, plus any non-tax revenues. Currently, the tax to GDP ratio is 21.0%.

The final element of the medium-term fiscal strategy is to improve the government’s net financial worth over time. This element broadens the focus of the fiscal strategy beyond the forward estimates, with the intent of improving the sustainability of the balance sheet. No numerical targets have been set here, so this element of the medium-term strategy does not have a large impact on policy decisions as yet.

Rather than focusing on the oft quoted net debt figure, which only includes debt-like instruments, net financial worth provides a broader measure of the financial position, by including superannuation liabilities, equity and other financial assets, as well as debt liabilities. Currently, Australia’s net financial worth is -11.8% of GDP, made up largely of the net debt liability and the net superannuation liability.

Australia’s medium-term fiscal strategy has been a success so far.

By basing the strategy on the relatively simple, flexible and robust target of surplus on average over the medium term, it is has become widely accepted in the community and a keystone of public financial management.

By continuing to meet the strategy, governments of both stripes have earned fiscal credibility. And while most definitely not the only factor at play—continuous economic growth and a terms of trade boom have also played major roles—it has helped turn Australia’s fiscal position into one of the strongest in the developed world.

Of course, no strategy is perfect. By failing to define what the medium term is, the strategy leaves open the question of how large the surplus should be, and over what period the average should be calculated over.

For instance, given that the economy has grown at or above trend for most of the 13 years that it has been in force, there is an argument that the surpluses in the good times were smaller than would be necessary to ensure surplus over the cycle (to use the original phrasing). Taking the projected budget balance over the forward estimates into account, the average budget balance since 1996 would be just that—a balance of +0.04% of GDP.

Further, over the period since 2004, Australia has been subject to a sustained terms of trade boom, resulting in “rivers of gold” flowing through the treasury’s door. With no formalized way of dealing with elevated commodity revenues within the strategy, it is possible that if the surpluses are not large enough during the boom years, following the strategy as is opens the economy up to a large fiscal adjustment should the terms of trade revert back to historical levels.

Finally, and as a consequence of the terms of trade boom, holding to the target of surplus over the medium term can provide a pro-cyclical impulse to the economy, as elevated revenues from high commodity prices lead to increased spending/lower taxes, even while maintaining a headline surplus. This contrasts to targeting a structural balance/surplus, which (depending on the method of calculation) would look through the impact of a terms of trade or asset price boom, thus avoiding pro-cyclical spending.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Jason Harris is a Technical Assistance Advisor at the IMF. He previously worked in the Australian Treasury preparing the Commonwealth Budget, and as an economic and fiscal adviser to the Australian Prime Minister. He also spent two years on secondment to the Papua New Guinea Treasury, helping to prepare the PNG Budget.

[2] Australia operates on financial years beginning on July 1, which are named in the form 2012-13. For simplicity, all financial years in this note are referred to by the first year, e.g., 2012 is actually 2012-13.

[3] The reduction in net debt was also due to asset sales over the same period.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.