Global leaders meet once a decade for the United Nations’ Financing for Development conference, which promotes funding for development spending in low- and middle-income countries. This year’s version took place in June, and given the backdrop of rising debt burdens and falling aid totals, discussion focused on how ministries of finance can make more of their internal sources and assets. For many, collecting more tax and enhancing public financial management (PFM) requires capacity development. The IMF’s Global Public Finance Partnership (GPFP), a multi-donor partnership created in 2024 to enhance the quality of capacity development, will play a leading role in supporting these capacity development needs.

The event’s official communique, the Seville Commitment, included a call to double official development assistance to help countries generate more internal revenue. Since then, the United Nations General Assembly endorsed the statement. But this does not assure the desired surge in funding – the targets are voluntary.

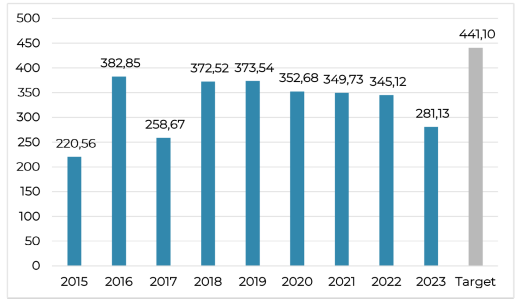

Leaders made a similar call to action a decade ago at the previous Financing for Development conference, held in 2015 in Addis Ababa. After that conference, a group of 20 donor countries committed to fund more capacity development for taxation specifically. Official development assistance in 2023 rose 27 percent from 2015's total, but still missed the intended target. The 2015 conference nonetheless helped increase aid for several years before the drop that characterized conditions leading up to Seville.

|  Figure 1 illustrates the decline in funding for fiscal capacity development from the 20 donor countries in the Addis Ababa Tax Initiative. Source: Addis Tax Initiative

|

The IMF’s fiscal capacity development underpins macroeconomic growth in low- and middle-income countries. But the IMF can’t do it alone – it relies on external financial support. The GPFP offers development partners a way to pool funds and work together in support of this capacity development with help from IMF data and expertise generated through its lending and policy advice.

Seville’s communique shows how thinking has evolved since Addis: it broadened the focus to include other forms of in-country financing. Leaders moved beyond domestic revenue mobilization, which is focused on taxation, towards wider concept of domestic resource mobilization, which includes all forms of capital available for use in both the public and private sector. They also prioritized PFM – a fair tax regime isn’t enough, they concluded. Governments must also spend wisely.

Can the Seville Commitment deliver lasting impact? We’re thinking about these three questions to anticipate the future of fiscal capacity development and the GPFP’s role:

Can the Seville Commitment reinvigorate fiscal capacity development funding?

Conference delegates noted that the statement was both ambitious and ambiguous. While it aims to double the amount of aid available for raising revenue, it did not provide a specific starting point or baseline year to measure against. It also lacks targets for PFM support or other areas of public finance.

The momentum created in Addis had slowed leading into the Covid-19 pandemic, and the slump that began in 2023 is likely to continue. Official development assistance of all types dropped in value in 2024 by 9 percent, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The figure is projected to fall at least 9 percent further in 2025.

However, even if Seville Commitment’s call to action falls short, it could still deliver a funding increase for fiscal capacity development.

How should capacity-development spending address PFM?

The Seville Commitment includes substantive passages calling for capacity development to improve the efficiency and quality of public expenditure, including budget transparency, data-driven procurement processes, and oversight roles for parliaments and supreme audit institutions.

Capacity development is a slow and steady process, in which benefits build up slowly instead of in quick bursts. Improved spending requires actions in many complex areas including program design, resource allocation, execution, and monitoring.

Infrastructure projects are an example of public spending that demonstrates the challenges involved in spending wisely. They are critical for growth, but can also backfire when governments overpay, or pick the wrong projects. According to IMF research, more than one third of all spending on public infrastructure is lost to inefficiency. For that reason, more than 80 countries based their PFM capacity development process on an IMF Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA). It identifies expenditure and process gaps, which countries can use to request customized capacity development programs.

Can capacity development deliver bigger impact with smaller budgets?

Getting the greatest value from the available funding requires collaboration. Recipients consider the IMF a preferred option to deliver capacity development, but the Fund can’t do it alone. It created the GPFP in 2024 to ensure that our demand-driven and results-oriented approach aligns with the reforms prioritized by local leaders, thereby enhancing impact.

As the leaders in Seville return to their countries and consider national-level implementation strategies, collaboration and integration should be a priority. The GPFP’s approach is especially relevant for countries currently borrowing from the IMF, as it provides an opportunity to integrate longer-term capacity development support with the urgent needs being addressed through lending programs. We look forward to the discussions to come with our peers to ensure the GPFP can support Seville’s agenda and maximize impact in member countries.