Weaknesses in public governance heighten risks that corrupt acts may take place. Analysis of these vulnerabilities is a starting point for understanding the potential causes of corruption and the measures that should be taken to manage or mitigate them. Governance vulnerabilities are often associated with another important concept, namely fiscal risk, but the two concepts are not identical.

In this blog we (i) clarify the relationship between governance vulnerabilities and fiscal risk, (ii) explain how IMF tools can be used to analyze these risks and manage them, using state-owned enterprises (SOEs) as an example; and (iii) discuss how to increase the synergies between fiscal risk management and the understanding of corruption vulnerabilities.

First, some definitions. Governance vulnerabilities comprise the specific characteristics of systems, mechanisms, and processes that can be exploited by corrupt people/groups or that may support or facilitate their corrupt activities. Examples include a weak legal framework for budgeting or revenue collection that allows officials and politicians to exploit loopholes for private gain, or an absence of effective sanctions and penalties for non-compliance with the law. Shortages of human capacity for preparing or executing the budget, undertaking debt management operations, or collecting taxes exacerbate these vulnerabilities.

There may also be absent or inappropriate rules for delegating authority to the financial managers and accountants who operate these legally defined systems. Lack of open and competitive public procurement, transparent fiscal information, effective control systems, and weak external accountability to the legislature, the national audit office, civil society, and the media are other major sources of governance vulnerability. Finally, the rules for operating financial IT systems may be ignored, bypassed, or broken as happened in the infamous 2013 “Cashgate” crisis in Malawi.

What about fiscal risks? Fiscal risks have been defined in the IMF’s Fiscal Transparency Handbook as “factors that may cause fiscal outcomes to deviate from expectations or forecasts”. These risks may be macroeconomic in nature – for example, when there are unexpected deviations in the forecasts of GDP, inflation, interest rates, world oil prices or other key economic indicators. Generally, macroeconomic risks do not directly create governance vulnerabilities.

A second type of fiscal risk arises because of the realization of contingent liabilities or other uncertain events such as a natural disaster, the rescue of a troubled SOE, a local authority or a major PPP project, or the collapse of a financial institution. Some of these risks may be triggered by international events such as a global financial crisis, a crash in commodity prices, or a severe hurricane, or may have a domestic cause such as excessive off-budget financing of an SOE. The connection with governance vulnerabilities in some of these cases may be weak, but in other cases not so, as with a third type of fiscal risk, associated with governance and policy issues. There is a close association (not discussed in this article) between fiscal risks and the absence of fiscal transparency.

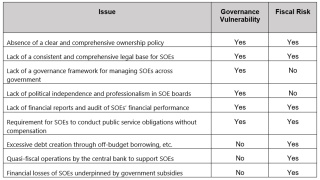

Let’s now illustrate these relationships with the example of SOEs. These companies are both a prominent source of economic activity in many countries, as well as a fertile breeding ground for corruption. Governance vulnerabilities in SOEs may stem from many sources. Prominent examples are the absence of an effective ownership policy, political domination of their boards of management, lack of effective oversight by the finance ministry or the legislature, or failure to produce financial statements and conduct robust audits of the companies’ financial performance. Many countries have not established a robust governance framework that applies to all SOEs. In Mozambique in 2013 over $US1 billion of loans to two SOEs to purchase ships for the coastguard service and for tuna fishing was laundered and transferred to illegal offshore accounts, while politicians and officials accepted large bribes. Governments may require SOEs to conduct public service operations (such as a house building program) that are outside their core mandate and reduce their profitability. Central banks may lend to them at below market-determined interest rates or use them for quasi-fiscal operations. Frequently, there is an absence of effective financial oversight by the finance ministry or the parliament.

The table below shows that in some of these cases governance vulnerabilities may arise, in other cases fiscal risks, in some cases both.

Tools exist to help countries analyze their governance vulnerabilities and fiscal risks and devise strategies for managing and mitigating these risks. In the case of SOEs, measures could include an approved ownership policy; better, more timely and more transparent data; improved governance arrangements (e.g., board structures at arms’-length to the government, and professional management); better oversight by finance ministries; and more rigorous and timely external scrutiny.

In 2018, the IMF’s executive board approved a framework for analyzing governance vulnerabilities. The framework has been applied in several countries in Africa and other regions. On fiscal risks, the IMF has developed a Fiscal Risk Assessment Toolkit (FRAT) – Fiscal-Risks-Toolkit-FRAT (imf.org) - for helping countries measure, monitor, and manage these risks. These tools include the Fiscal Transparency Code and Fiscal Transparency Assessment, as well as specific tools dealing with SOEs, contingent liabilities, PPPs, and other risks. The FRAT can be used to support the IMF’s assessments of governance vulnerabilities in Member Countries.

To conclude, governance vulnerabilities embrace a broader set of characteristics than fiscal risks, and the two concepts are not identical. There are types of governance vulnerability that are not fiscal risks and types of fiscal risk that are not governance vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, the two categories of risk are closely related. The management and control of these risks require an integrated approach using a variety of policies, tools, and CD support. Where governance vulnerabilities arise, fiscal risks are also likely to be present, and vice versa. Fiscal risk is a core component of many types of governance vulnerability, and the management and control of these risks is key to reducing these vulnerabilities.

[1] Racheeda Boukezia and Lesley Fisher are Senior Economists in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department. Richard Allen is a global consultant in public finance and Co-Editor of the IMF’s PFM Blog.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.