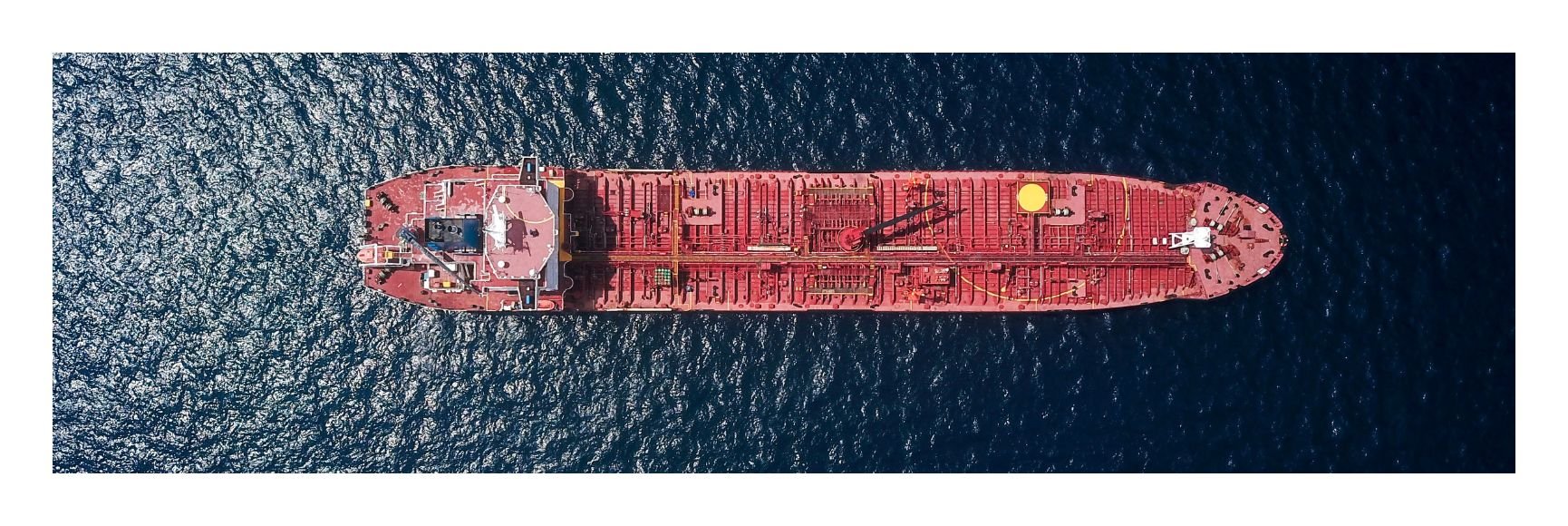

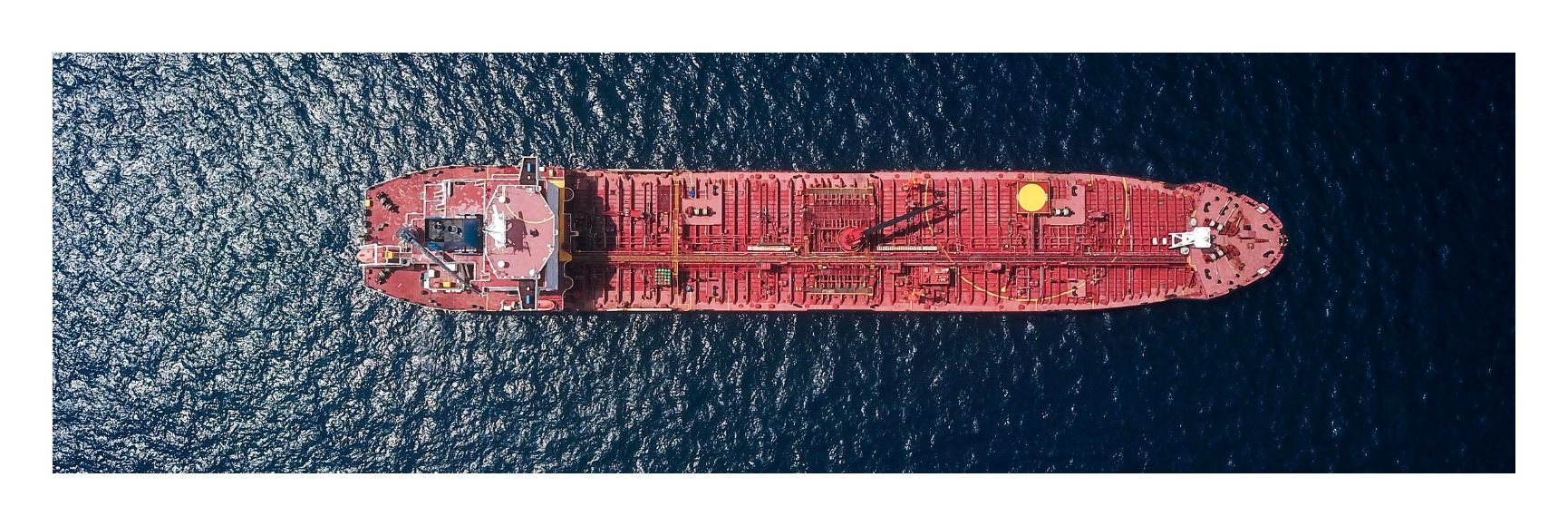

Many governments are facing fiscal distress and in the more extreme cases a crisis requiring debt restructuring. Their situation is similar to that of a ship out of fuel and adrift on the high seas. Even if it is lucky enough to be offered a rescue, it will not help just to get the ship refuelled if the holes in the hull and fuel tank are not also repaired.

It is not uncommon for companies and individuals to have difficulty meeting their payments. If the difficulties are serious enough to pose a high risk of default, it may be possible to negotiate with creditors to reduce the debt servicing burden and avoid default. A company or individual in these circumstances is, however, first expected to account for all their assets as a quid pro quo for accessing debt relief. A corporate restructuring would also involve not only optimizing the capital structure and questioning the entire structure of the business, but also a review of operational efficiency, to stop the leakage and improve the cash flow. A key component of this review process would be determining whether better value could be extracted from the firm’s assets.

For countries the processes are often less formal, but financial markets, supranational organisations, or taxpayers - whoever is being asked to take the strain - may wish to be assured that a similarly rigorous assessment has been made.

The good news is that in the public sector, at all levels of government and in all countries, the asset side of the balance sheet frequently offers an immense untapped potential in the short and long term. The total value of public sector assets globally is approximately 2xGDP. Professionally managed, this portfolio of assets could generate additional revenues to the government equivalent of at least 3% of GDP, every year. These assets consist of public infrastructure, real estate, and operational assets such as state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

It is not unusual in countries with a substantial portfolio of SOEs, that just a handful of these largest companies instead cause a fiscal drain equivalent of at least 3% of GDP.

Managing public assets professionally will not only offer a longer-term solution to stop this leakage but can also create fiscal space by developing the assets so they generate a steady stream of surpluses. Developing the assets will also increase their value. The alternative to selling a well-maintained and fully developed asset is to rent it out and use the cash flow to service the debt. Regardless of whether the intention is to ultimately sell the asset or enjoy the annual returns from its operations, increasing the value by developing it to its best use will be beneficial. There is also the benefit that governments with stronger net worth (assets minus liabilities) recover faster from recessions and have lower borrowing costs.

Salvaging a leaking ship is best done by professionals. Managing and developing public assets is no different. The evidence is overwhelming that politicians and civil servants are not successful in performing entrepreneurial functions. Nor is a political bureaucracy designed to manage commercial risk, which is why the ownership and governance of public commercial assets requires an independent institutional structure, a holding company. This could take the form of a public wealth fund which is able to work in the same way as would a private sector owner. Such public wealth funds bring the same governance, management, accounting, and accountability arrangements to specific asset pools as are used in the private sector.

With public wealth funds, the benefits of efficient management can be realized without wholesale privatisations. At the same time, well-managed non-core assets could be disposed of in a way that gives a better return to the taxpayer. This would be done by a capable team of expert managers as part of the broader business plan for maximising the yield of the entire portfolio of government assets.

Like ships heading into a storm, many governments are now facing a fiscal crisis. This strain on public finances globally demands radical action from international financial institutions aiming to help governments in fiscal distress. Rather than throwing good money after bad, it is imperative to consider what holes in the fiscal ship can be plugged by improving the yield from the vast portfolios of hidden public assets. The evidence is clear: commercial management of public assets delivers significant gains that can no longer be ignored.

[1] Ian Ball was a principal architect of the New Zealand government’s financial management systems; John Crompton is an investment banker and a former HM Treasury official, and Dag Detter is a principal of Detter & Co.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.