Posted by Gary Bandy, Mark Johnson, Tia Raappana, and Srinivas Gurazada[1]

What do governments need to be effective in a crisis? Among many other things, they need to be good at risk management, at securing the necessary resources and spending them where they matter the most, as quickly and effectively as possible, whilst balancing many policy priorities and demands. To do all this, a government needs good PFM systems. Often, governments with weak PFM systems will find those weaknesses exposed and magnified during times of crisis or extreme fiscal pressure.

Over the past two decades, the focus of many countries has been to build robust, efficient, and accountable PFM systems. The Global Report on Public Financial Management by the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) program[2] highlights that whilst PFM systems have seen improvements, significant weaknesses remain. Countries, on average, perform better preparing their budgets than getting them implemented.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put PFM systems under further stress. A recent report by the ACCA[3] on Rethinking PFM explores what lessons governments and finance professionals can learn from the COVID-19 crisis experience. In particular, the report considers two important questions:

- How well did governments respond to the pandemic?

- What are the future challenges for PFM arrangements?

The report draws on a wide evidence base, including a global survey with over 1,500 responses, three roundtable discussions with 45 PFM practitioners, interviews with experts, and a review of recent PFM literature.

It highlights the challenges for governments in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments had to think fast about what to do and then act fast to implement policies and save lives.

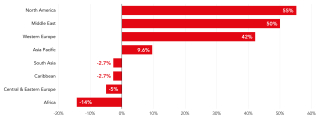

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the global survey showed that PFM practitioners in wealthier regions - North America, Western Europe, and the Middle East - were significantly more positive about their governments’ responses than in other regions (see Chart).

Chart: Did governments respond effectively to COVID-19? (Positive minus negative responses)

But what role did PFM play? Governments may have been agile and determined, but often had to bend or stretch their PFM systems to achieve their objectives. Some legislatures had to approve multiple supplementary budgets, while others granted extraordinary spending powers to the executive. Executives suspended the normal rules of procurement and accountability to respond faster to the emergency.

The survey results indicate the need for governments to make further improvements to ensure their PFM systems are flexible and resilient enough to deal with crises in the future.

ACCA’s report identifies six areas for greater focus in the post COVID-19 world, to ensure that PFM systems are ‘fit for the future’:

- Improving transparency and accountability of government spending, so that the public can be confident about the use of public money – especially during a crisis.

- Improving the linkages between governments’ strategic plans and the allocation of resources, because too often budgets do not reflect the key policy priorities governments set for themselves. Choices made during a crisis can have a major impact on future budgets.

- Intensifying the focus on risk management, to enable public organisations to become more resilient. The use of risk management tools is critical when allocating resources to programmes and investment projects. Also important is integrating climate change into financial risk management

- Focusing PFM improvements on service delivery - concrete outcomes for citizens – by asking the service delivery providers on the ground what kind of services they need to deliver, to whom, and using what PFM systems and tools?

- Implementing accrual basis accounting in governments, along with a broader balance sheet approach in public finance, to provide more comprehensive financial information for better decision-making.

- Improving transparency in procurement, for example through e-procurement and the Open Contracting Data Standard. At least US$ 1 trillion is wasted every year globally due to inefficient and short-sighted procurement practices.

We also often forget that PFM systems are only as good as the environment they work in, and the people who operate and manage them. For that reason, 11 of the report’s 21 recommendations relate to PFM operators, practitioners, and managers. To benefit from their improved PFM systems, governments may need to make a significant and sustained investment in human resources including their leadership capabilities, skills, and the incentives that support them.

Governments can be better prepared for future crises, whether health-related, economic, or climate-based, by focusing on the areas identified in Rethinking PFM. This will create new challenges as well as opportunities for all partners working on PFM around the world – including those who research how PFM systems should work, diagnose how they perform, and support the people who work in them.

[1] Gary Bandy is a PFM consultant in public financial management and co-author of the Rethinking PFM report. Mark Johnson is the senior subject matter expert for the public sector at ACCA. Tia Elise Raappana is a Senior Public Sector Specialist in the PEFA Secretariat and Srinivas Gurazada is the Head of the PEFA Secretariat.

[2] The PEFA program is a partnership of the European Commission, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and the governments of France, Norway, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the Slovak Republic, and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Over the last 20 years, the PEFA assessment framework has become the acknowledged standard for diagnosing the overall performance of PFM systems. It has been used in more than 150 countries with over 650 assessment reports around the world.

[3]ACCA is the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, a thriving global community of 233,000 members and 536,000 future members based in 178 countries and regions that upholds the highest professional and ethical values.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.