By Manal Fouad, Todd Schneider, Natalija Novta, Gemma Preston, and Sureni Weerathunga[1]

Many small and fragile countries are both highly exposed to the adverse effects of climate change and have extremely limited resources. For some, the existential nature of the climate threat highlights the criticality of adapting to climate change—investing in infrastructure and other key areas to increase resilience and lessen the impact of climate-related natural disasters on growth and public welfare. Many small states have only a fraction of the financial resources needed to finance climate adaptation initiatives and rely on development partners and climate funds to access such financing. Yet, the experience in the Pacific Islands Countries has shown that financing has fallen short of the climate adaptation needs and that more will need to be done to unlock climate finance at the pace needed to respond to climate challenges. Maintaining the status quo will not be enough.

A new joint departmental working paper just published by the Fiscal Affairs and Asia-Pacific Departments of the IMF examines access to climate finance by Pacific Island Countries. It highlights both the successes and challenges and draws broader lessons for small and fragile economies.

Adaptation costs for Pacific Island countries are significant in relation to their economic size. The average investment needs for climate-proofing infrastructure are estimated between 6 and 9 percent of GDP annually for Pacific Island countries – or almost $US 1 billion in total for the region - each and every year for the next 10 years. Many of these countries have little or no fiscal space, and no access to domestic or international debt markets. Still others are reeling from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the sizeable increase in public debt that emerged as these countries saw revenues plunge. This means that they need access to grants and concessional loans to be able to sustain investment in resilient infrastructure on the scale needed for the next 10 years.

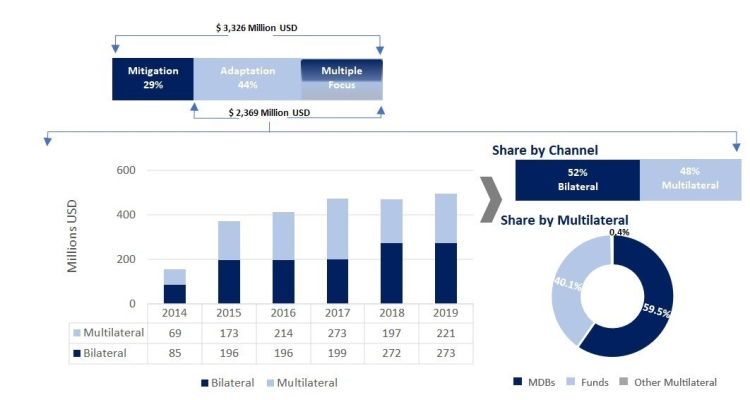

The good news is that in the six years between 2014 and 2019 - about $US3.3 billion has been approved for climate projects. This includes financing from bilateral and multilateral sources and from both adaptation and mitigation projects.

Track record of access: $3.3 billion has been committed for projects in the Pacific (2014-2019)[2]

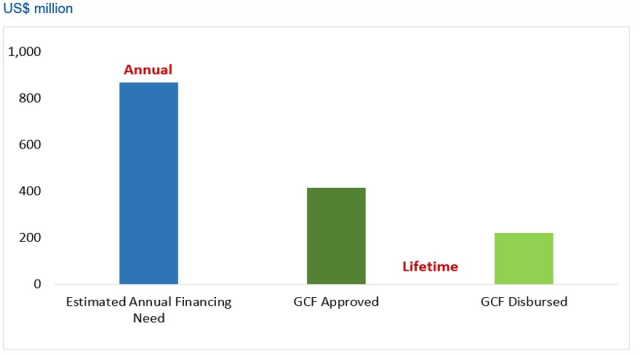

But, given that estimated needs for adaptation alone are almost $US1 billion each year for at least 10 years, this still leaves a big gap between the financing needed, the financing approved, and actual disbursements (that is the money actually hitting the ground). For example, looking at the Green Climate Fund (arguably the dominant global climate fund) total approvals for the Pacific Islands through May 2021, are only about half of the estimated annual needs. And the total disbursements are only around a quarter of the annual adaptation needs.

So far climate finance has fallen short of estimated adaptation needs[3]

Successes and Challenges in accessing financing from Climate Funds

Many countries want to access finance from a climate fund directly because it gives them the most control and ownership over their projects. But this approach requires accreditation which countries have found challenging.

- Small and fragile countries find that the accreditation process is lengthy and complex, due to the volume and intensity of requirements—despite streamlining attempts by climate funds. Accreditation often also necessitates tremendous efforts by countries to deliver reforms to meet requirements where capacity is already very thin. Accreditation for direct access currently takes between 2-5 years for Pacific Island Countries, and re-accreditation is required every 5 years.

- The requirements are many, and having robust public financial management systems and processes is only one of these. From a PFM perspective, capacity in audit, procurement and robust financial control frameworks are important to meet the accreditation requirements of climate funds.

- Lastly, accreditation is only the first step to unlocking climate finance. Once accredited, countries need to develop specific projects, prepare concept notes, get projects approved and then begin to implement the project for disbursements to begin. This requires a different kind of capacity, particualry in Public Investmetn Management. Again, in the Pacific Islands (as in small developing states globally) capacity constraints pose a serious challenge in this regard.

Another way to access climate finance is through partnerships with international accredited entities (like the World Bank, ABD or UNDP etc.) Accessing the Green Climate Fund through international accredited entities has been the most successful avenue for Pacific Island Countries to date in terms of the size and speed of financing. This path works well to provide finance where the priorities of countries and the international accredited entities align. Where priorities diverge, or where projects are simply too small relative to the overall project portfolio of international entities, access through this pathway can be challenging.

The international community can work together to meet this challenge head on

To improve access to climate finance, the international community must work together with climate-exposed countries to meet this challenge head on. We have identified what each of the key actors – Pacific Island Countries, climate funds and the IMF – can do to help:

- Pacific Islands Countries should take a strategic view of how to best match climate adaptation projects with potential funding sources and delivery partners. Where resources allow, dedicated climate units that take a whole-of-portfolio view to managing climate finance could establish financing strategies, integrate climate finance into the budget process and be a key link across government ministries, managing coordination challenges. Pacific Islands Countries should continue to build necessary PFM capacity. Strong audit, robust control frameworks and strengthened public investment practices are important priorities for accreditation.

- Climate Funds recognizing the shrinking window of opportunity to address the climate crisis, should consider further streamlining accreditation requirements, and prioritizing those requirements that will significantly strengthen safeguards for shareholder resources. We also recommend increasing reliance on ex-post compliance and other innovative options that could help to further reduce the burden on countries.

- The IMF will continue to provide targeted capacity development assistance to strengthen PFM in the Pacific Islands Countries, helping to integrate climate considerations into PFM reform plans tailored to country capacity. In addition, the IMF will provide further analysis and discussion of climate risks, mitigation goals and adaptation needs of individual countries in the context of macroeconomic surveillance, disseminate lessons learned from analytical work to the global membership and use its convening power to bring relevant stakeholders together to discuss improvements to climate finance.

For more, the full paper can be found here: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2021/09/23/Unlocking-Access-to-Climate-Finance-for-Pacific-Islands-Countries-464709

[1] Manal Fouad is Assistant Director in the IMF Fiscal Affairs Department (FAD) and Chief of the PFM 2 Division, Gemma Preston is a PFM Technical Advisor, FAD and Sureni Weerathunga, Research Analyst FAD. Todd Schneider is Division Chief of Pacific Islands Division in the Asia-Pacific Division (APD) and Natalija Novta is an Economist, APD.

[2] Source: IMF staff; and OECD Climate-related Development Finance Database (2020)

[3] Sources: Green Climate Fund (GCF) website; IMF “Fiscal Policies to Address Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific.” IMF Departmental Paper; and IMF staff calculations. Note: GCF data as at May 2021.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.