By Nicholas Travis, Manisha Marulasiddappa and Tim Cammack [1]

There is increasing recognition by practitioners that PFM systems have an important role to play in supporting service delivery outcomes. This is reflected by a recent conference on the topic and has accelerated as a result of Covid-19, with numerous articles published on the importance of budget flexibility, particularly in the health sector.

The focus on service delivery outcomes represents a welcome shift towards a more developmental approach to designing PFM reforms. However, the complexity of service delivery makes it difficult to pinpoint specific PFM components that are most relevant to sectoral goals.

To overcome these challenges, recent diagnostic studies have attempted to identify and assess financial bottlenecks (FBNs) which inhibit service delivery. Our recently published working paper explores this approach in detail based on recent experience in Myanmar.

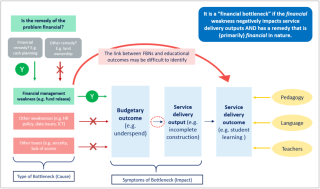

The methodology seeks to understand how PFM systems inhibit the transformation of financial inputs into sector outputs. The identification of FBNs depends on two criteria: (i) their significance for the delivery of sector outputs; and (ii) the extent to which they can be resolved by improvements in financial management. Figure 1 explains these criteria further with application to the education sector. Critically, FBNs are not defined by the typical measures of value-for-money (i.e., efficiency, effectiveness and equity) but by the underlying causes of why such outcomes may be suboptimal. For instance, time-consuming procurement processes that result in inefficiencies in school construction.

Figure 1: Identifying financial bottlenecks in the education sector – a suggested typology (click on the figure for a better image resolution)

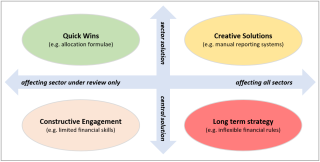

In practice, there are many possible FBNs and it is often difficult to quantify their impact on service delivery. For example, is excessive rigidity in virement rules a more significant bottleneck than the absence of a medium-term budgeting perspective? The challenge for assessors is to develop a manageable list of bottlenecks using the criteria above and to identify solutions that generate ownership among key stakeholders. The matrix in Figure 2 below may be helpful in achieving this. It distinguishes FBNs by understanding the extent to which the agency has control over them, making the resulting reform action plan more realistic.

Figure 2: Prioritising FBNs according to their relative ease of resolution (click on the figure for a better image resolution)

The key contribution of FBN studies is their emphasis on the nexus between financial management and sector outputs. This explicitly problem-driven and bottom-up approach demands intensive engagement with stakeholders at central and sub-national level to analyse the functionality of the PFM system as viewed by budget users. The end goal is improvements in service delivery rather than in financial management. Furthermore, the depth of analysis needed to verify and prioritise FBNs requires extensive stakeholder consultation, enhancing buy-in to the resulting action plan. As such, the approach shares many of the characteristics of contemporary methods such as Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA).

FBN studies focus on underlying systemic problems that impact service delivery. They can, therefore, serve as a complement to Public Expenditure Reviews (PERs) which focus more on the efficiency and effectiveness of resource use. Also, FBN studies with their demand-driven approach to identifying bottlenecks and solutions may be more welcome than tools such as Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS) which have a relatively narrow focus.

Our experience in Myanmar identified several unresolved methodological issues:

- First, how can we define ‘financial bottleneck’ in order to maximise the value added by the FBN method? The focus on budgetary systems seems appropriate, but what about related systems that impact value-for-money? For instance, human resource management systems that impact the efficiency of salary expenditure. An agreed definition is needed if the term is to be the lynchpin of an effective diagnostic.

- Second, what determines the ‘significant outputs’ for a sector to create a starting point for the identification of FBNs? Is there a consensus amongst sector specialists about which outputs are critical to outcomes? How should these be ranked?

- Third, how do we judge which PFM weaknesses are the most important for outputs? Some, such as short releases of funding, are relatively straightforward. But what of those weaknesses whose impact on sectoral outputs is indirect, such as failures in reporting or internal controls?

- Fourth, how can we address FBNs not identified by budget users themselves? These might include the lack of a results focus in the budget; or an absence of transparency/accountability. What is the appropriate trade-off between a problem-driven and top-down approach?

- Finally, do we need to accept that FBN studies cannot cover all potential issues? A sector-wide search for FBNs requires extensive research. Should studies focus just on particularly troublesome sectoral issues? Or perhaps the method should limit itself to problems that are actionable by the sector ministry alone?

Resolving these challenges will clarify the purpose and method of the FBN approach. However, our experience in Myanmar suggests they do add significant value, particularly in generating greater awareness of PFM challenges among sector officials and in securing ownership of reforms. It also suggests that the approach is replicable across countries and sectors, as the methodology is flexible enough to accommodate differing levels of emphasis and customisation. FBN studies may have most value when prepared together with sector policy specialists, human resource management experts and others.

[1] The authors are all Associate Consultants in Public Finance for Oxford Policy Management.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.