Posted by John Grinyer[1]

Realistic budgeting is vital to good public financial management. Get the numbers wrong and a plethora of problems can emerge - cash shortages, a buildup in arrears, cutbacks on capital investment spending, delays in paying salaries, and so on. Consequently much technical assistance over the years has focused on strengthening forecasting skills, in particular on revenue, which is of crucial importance given that the projected resource envelope is often the starting point for preparing the coming year’s budget.

Nevertheless, agreeing the revenue forecast is not only a technical exercise, politics is often at play, especially where there is a separate revenue collection agency which is now the norm in most countries. The classic set-up is the finance ministry wanting ‘high’ targets, the revenue authority ‘low’, with the optimum being something ‘stretching but achievable’. The situation is further complicated when there is performance-related pay scheme in the revenue agency directly linked to revenue targets, adding greater impetus for revenue authorities to resist high forecasts.

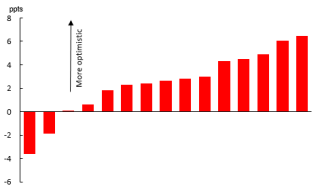

Nevertheless, in the battle between the revenue authority and the finance ministry, the finance ministry seems to come out on top – with there being a clear tendency toward optimism in the country forecasts (see first chart). This supports anecdotal evidence from the budgeting process. For example, there are last minute increases in revenue targets to accommodate additional spending requests, or the Minister boosts revenue numbers the day before the budget speech so to keep within a deficit target or borrowing ceiling - at least on paper. To the frustration of many finance ministry economists, ‘technical’ forecasts are often overruled and instead an unduly optimistic set of numbers appears in the budget book.

5-year average mean variance in non-grants revenue growth forecasts (2012/13 – 2016/17)[2]

Perhaps it is time to look beyond the technical side of revenue forecasting and acknowledge the politics? A revenue forecast is more than just a spreadsheet. How best to govern the revenue forecasting process to mitigate the risks of ‘optimism bias’?

Encouraging dialogue between the finance ministry and the revenue authority would appear a good first step. Each institution would present their own views on the revenue outlook, efficiency gains, and tax elasticities, and attempt to agree a common position. These discussions have greater influence when senior management are involved, and all parties understand and agree with the assumptions that underpin the forecasts and are prepared to defend them publicly and in Cabinet.

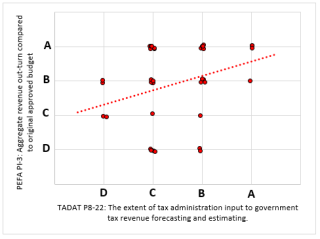

Correlation between most recent PEFA score (PEFA PI-3) and TADAT score (P8-22) for 38 countries

The benefits of collaboration appear to be borne out in the data presented in the second chart. Taking a sample of the 38 countries who have undertaken both a TADAT[3] and a PEFA[4] shows a positive correlation between revenue forecast accuracy (PEFA PI-3) and tax administration input to the forecasting process (TADAT P8-22). Good performing countries tend to have a specialized unit in the revenue authority working with their counterparts in the finance ministry to produce an agreed set of forecasts. Conversely, poor performers do not engage in such dialogue, and have a tendency for the finance ministry to steam-roller through high revenue targets with no discussion.

Understanding where you went wrong in the previous year’s forecasts is also valuable. Three of the top performers undertake joint monthly or quarterly reviews of revenue receipts. Variances from targets are analyzed and explained. This can help to iteratively improve forecasting performance, and to highlight the errors created by last minute changes to revenue targets by policy makers. Such variance analysis can identify if a suspect GDP forecast was to blame, or an overly high assumption made on improvements in revenue collection efficiency.

Given the serious consequences of overstating your revenues in the annual budget and subsequently running out of cash, more attention should be given to this key area. Successful revenue forecasting requires more than just an elaborate Excel model. Dialogue, understanding and trust between key stakeholders, especially the revenue authority and finance ministry, is vital if you are going to keep your finances in the black. Exchanging information with forecasters in other ministries, think tanks or universities can also be helpful.

[1] John Grinyer is Regional PFM Advisor at the IMF’s Regional Technical Assistance Center AFRITAC West 2, based in Accra, Ghana (http://www.afritacwest2.org/). Thanks to Patrick Ryan for his help in compiling the TADAT and PEFA data.

[2] Sample of 15 sub-Saharan countries. With thanks to Bryn Battersby, regional macro-fiscal advisor with AFRITAC East, for preparing this chart.

[3] Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool. As the P8-22 methodology changed during TADAT piloting, the sample is restricted to TADATs undertaken using the November 2015 field guide. See http://www.tadat.org/ for further information.

[4] Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Assessment. Where countries have undertaken multiple PEFAs the most recent score is used. See https://www.pefa.org/ for further information.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.