Posted by Neeraj Patel[1], Mario Pisani, Nathanaël Benjamin[2] and William Durham

On 21 June 2018, the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Governor of the Bank of England unveiled new reforms to the Bank's financial framework, intended to boost transparency, reinforce the Bank’s resilience and independence, and strengthen its capacity to support the financial system.

===

The Bank of England, or “the Bank” to insiders, is the world’s second oldest central bank. For much of its history, it operated as a private institution, although always acting in the national interest. The UK government nationalised the Bank in 1946, at which point HM Treasury (the UK’s finance ministry) became its sole shareholder.

The Treasury has granted new powers to the Bank over time, from monetary policy independence in 1997 to prudential supervision in recent years. But the financial relationship between the Treasury and the Bank has remained broadly unchanged throughout this period.

Following the financial crisis, the Bank’s own finances have faced two key challenges:

- Capital: the Bank’s capital (or equity) has become low relative to the risks and exposures it currently faces, with its capital-to-asset ratio falling as its remit has expanded. The Bank’s total loss-absorbing capital now covers only about 1 percent of its non-indemnified risks. This means that the Bank has limited scope to implement a full range of monetary policy or financial stability tools using its own balance sheet.

- Income: The Bank’s principal income sources, derived from investment returns on a sterling bond portfolio, have become more variable in recent years. The Cash Ratio Deposit Scheme, which funds the Bank’s monetary policy and financial stability functions, required the Bank to fix its income and expenditure projections at the beginning of each 5-year period. The increase in the Bank’s responsibilities since 2013, twinned with volatile investment returns, which affect the Bank’s income over this period, have resulted in a mismatch between its income and expenditure.

Affecting both capital and income are the Treasury and Bank’s historic shareholding arrangements, where all the net income from the issuance of Banknotes (seigniorage) is passed directly to the Treasury, and the rest of the Bank’s net profits are shared with the Treasury in the form of dividends. Limited capacity to generate income from new sources means that the Bank cannot readily boost its profits, nor replenish its capital base through retained earnings.

Recognising the case for reform, the Treasury and the Bank worked together to address these twin challenges:

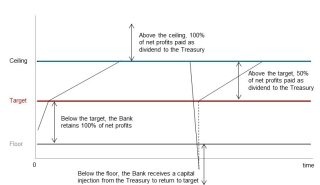

- New capital framework: the authorities agreed a new financial framework to make the Bank’s balance sheet, including total loss-absorbing capital, more resilient to shocks. This included, for the first time, a target level of capital for the Bank, based on the risks that the Bank expects to bear on its balance sheet under severe but plausible scenarios. This innovative framework, which will be reviewed every 5 years, injects flexibility into the Bank’s income-sharing arrangements, giving the Bank a mechanism to converge to its capital target organically over time (see chart). This provides certainty that the Treasury stands behind the Bank in the event of a significant capital loss, with a codified process for recapitalising the Bank if needed.

- New income arrangements: fixing income and expenditure for a 5-year period created uncertainty on how the Bank’s investment returns on deposits would materialise. Following consultation with market participants, a revised scheme was launched with a variable funding approach, allowing the Bank to review deposit rates every 6 months, and to respond to any changes in the market environment for investment returns.

The Bank of England’s Capital and Income Sharing Framework (Click on the image for a better resolution)

With the agreement of the Chancellor and Governor, and to support better public transparency, the authorities have published a new Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Treasury and the Bank, setting out the future financial relationship between the authorities.

The MOU includes a set of capital principles that clarify for the first time the types of operations that the Bank will undertake off its balance sheet (backed by its own capital), rather than through seeking a Treasury-backed indemnity as it has done in the past. It also includes better information sharing arrangements between the Bank and the Treasury on the Bank’s financial and capital position.

In June 2018, the Bank’s total loss-absorbing capital stood at £2.3 billion. But stress testing of the Bank’s balance sheet under severe but plausible scenarios implied a target level of capital of £3.5 billion. In a letter to the Governor, the Chancellor noted his intention “to provide a £1.2 billion capital injection from the Exchequer to the Bank’s balance sheet in the 2018-19 financial year”, to return the Bank’s capital to target in a fiscally neutral manner.

In line with the capital principles set out in the MOU, this injection will also enable the Bank to transfer the £127 billion Term Funding Scheme (TFS) onto its own balance sheet, removing the Treasury’s indemnity on this portion of the lending facility.

The Governor explained in his Mansion House speech on June 21 that “The additional capital will significantly increase the amount of liquidity the Bank can provide without needing an indemnity from HM Treasury to more than half a trillion pounds” to meet its monetary policy and financial stability objectives.

As a package, the new arrangements will support a stronger UK economy through a more stable financial system, as well as better transparency, accountability and reporting from the UK’s public institutions Regular reviews of the parameters of the framework will ensure that it is kept up to date in an evolving environment.

And as the Governor remarked in a letter to the Chancellor, by building a balance sheet that is fit for the future, the capital framework “will better align the Bank’s financial resources to its mission”, leading the way internationally for the finance ministry and the central bank to work together.

[1] Debt & Reserves Management team, HM Treasury, United Kingdom

[2] Financial Risk & Resilience Division, Bank of England, United Kingdom

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.