Posted by Richard Allen and Yugo Koshima[1]

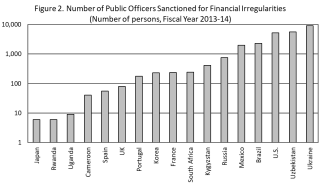

Financial irregularities arising from breaches of public financial management (PFM) laws and regulations are commonplace in countries at all stages of development. They can have a significant fiscal impact. In several countries, external auditors have reported financial irregularities amounting to more than 10 to 15 percent of the government’s total budgeted expenditure, equivalent to around five percent of GDP or more (Figure 1). In many of these countries, budget deficits could have been eliminated if there had been no irregularities.

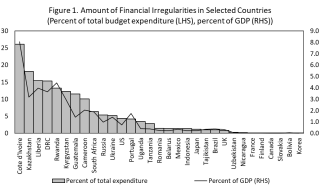

Many countries have developed a system of penalties or sanctions aimed at improving compliance with their PFM laws, but the practices followed to implement these regimes vary widely. For example, Figure 2 shows that the number of public officers sanctioned for financial irregularities in 2013-14 ranges widely from 6 persons to 9,101 persons among 17 countries.

In relation to public finance, sanctions are a poorly-understood tool for enforcing financial laws and regulations. Historically, they were regarded as a tool of retribution for public officers who failed to safeguard public funds. In principle, modern systems of sanctions should be designed to create the right incentives for compliance with PFM legislation, but many do not.

A recent paper on “Do Sanctions Improve Compliance with Public Finance Laws and Regulations?”, published in the journal Public Budgeting & Finance, attempts to open up a new perspective in a PFM area on which few previous studies have shed light. Drawing on Douglass North’s famous idea of formal and informal institutions, the paper analyzes not only the sanctions regime included in a country’s legal framework but also the institutional models for implementing this framework. By quantifying a relationship between sanctions and compliance, the paper provide a good place to understand the dynamics of this complex relationship.

It might be expected that a regime that imposes brutal sanctions on the perpetrators of financial irregularities would reduce such irregularities and improve compliance. However, an empirical analysis of sanctions regimes and recovery rates in 26 countries suggests that excessive use of “harsh” sanctions could negatively affect the level of compliance. If a sanctions regime is to be effective, it should rather meet the three core principles of impartiality, proportionality, and transparency. Case studies of three institutional models (“financial police”, “risk-based”, and “sanctions coordinator”) show that a model focusing on high risk areas is likely to ensure compliance more efficiently and equitably, without excessive cost, than a regime based on a “mass investigation, mass sanction” approach. The paper further lays out a tailored model that may be appropriate for countries facing capacity constraints. Such an approach could be integrated into a country’s anti-corruption strategy.

[1] Richard Allen is a Visiting Scholar with the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department. Yugo Koshima is an Economist with the same department.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.