Posted by Aarti Shah and Neil Cole[1]

Finance ministries throughout the world have a number of things in common. They are custodians of a country’s public finances. They also manage complex political processes and tend to attract smart people. Unsurprisingly, the job of a finance ministry official does not lend itself to popularity or friends amongst the public service fraternity. That may explain why when senior budget officials from a diverse range of countries are brought together, they have much to talk about.

Surprisingly, little has been written about how finance ministries operate, evolve, and adapt to ever-changing challenges. As part of a broader collaboration, three institutions currently thinking about capabilities (CABRI, ODI and the South African National Treasury) co-hosted a conference with the theme ‘Finance Ministries in the 21st Century’ in Johannesburg on 25 and 26 March 2015. Fifty-five participants from government, bilateral and multilateral development partners and other organizations[2] shared their experiences from over 20 countries on how finance ministries operate as organizations, and how they could do better.

Here are some highlights.

What capabilities does a finance ministry need?

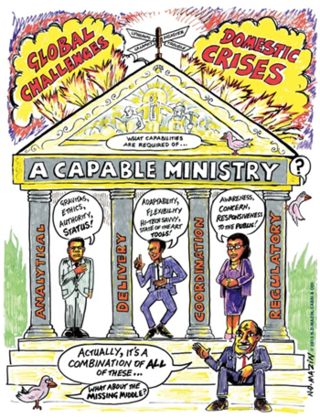

Recent research by the ODI[3] points to four types of capability: analytical, delivery, regulatory and coordinative. Different tasks require different combinations of these capabilities.

Analytical capability describes an organization’s ability to digest and process information and turn that into advice and political decisions. Delivery capability refers to the production of key deliverables on time, such as the budget, revenue collection and making payments. Coordinative capability is the ability to manage the activities of other parts of government to produce certain results and outcomes. Lastly, regulatory capability means the ability to control the production of particular services delivered by others.

The power and strength of finance ministries

The Johannesburg conference recognized that a staff position at a finance ministry comes with gravitas, ethical stature and the authority. The power of officials to say “no” and sometimes “yes” brings them respect if not widespread popularity. Yet, finance officials are highly dependent on others to do their job, making the capability to extract essential information from line ministries a critical career challenge. Building informal relationships with line ministry counterparts is as important as engagement through formal structures. Sometimes, finance ministries need be good storytellers as much as custodians of hard fiscal data.

The examination of capability in the public sector is not confined to finance ministries. Participants shared experiences of the uneven distribution of skills for formulating and analyzing new policies across government, and how this challenge could be addressed. In some cases, finance ministries use budget allocations to steer policy and, in other cases, they undertake the policy work themselves to fill a policy vacuum. Ideally, sufficient capabilities for policy analysis need to be built across government and not only in finance ministries.

Is fiscal stress a driver of innovation?

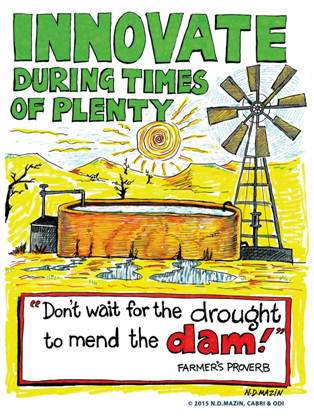

There was much debate about whether fiscal stress is a driver of innovation. Countries related their various experiences. In times of plenty, there is time to think but often innovation does not take place, as there are no pressing fiscal problems to solve. In times of stress, there is space to act but not always time to think how best to innovate. Inefficiencies build up in times of plenty and the consequences of these inefficiencies materialize in times of stress.

This dilemma raises several questions, which were discussed during the conference. How should finance ministries use times of plenty to help them prepare for times of stress? How should they use times of stress as opportunities to innovate? How much space should politicians allow finance officials to develop innovative ideas and policies, in addition to performing routine administrative tasks? How can finance officials use periods of plenty to build a stronger, more cooperative relationship with line ministries during times of plenty, and maintain these relationships during times of stress?

The conference highlighted the areas of capability that are important, relevant and underdeveloped. CABRI and ODI will jointly undertake further work to support the capabilities of finance ministries. For further information on the ‘Finance Ministries in the 21st Century’ conference please visit the CABRI and ODI conference webpages.

Note. The cartoons were part of a collection of seven drawn by Andy Mason from Azania Mania Art Kolektiv to capture key points made during the conference. This conference was part-funded with UK aid from the British people.

[1] Aarti Shah is an advisor at CABRI; Neil Cole is the Executive Secretary of CABRI.

[2] The countries represented were Benin, Botswana, Central African Republic, Ivory Coast, Finland, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mali, Niger, Seychelles, South Africa and Tunisia, together with representatives of DFID, AFRITAC South, GIZ, CABRI, PwC, ODI and the World Bank. Country experiences from Chile, Columbia, Germany, Mexico, Morocco and the UK, amongst others, were shared by the participants.

[3] Philipp Krause, Sierd Hadley, Shakira Mustapha and Bryn Welham. ‘The Capabilities of Finance Ministries’ (Conference copy). London: Overseas Development Institute

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.