Posted by Carlos Scartascini [1]

The Fiscal Affairs Department at the IMF has been a (if not the) leader on fiscal research, policy analysis, and data generation in the world for the last 50 years. It has influenced the work of scholars, contributed to the development of professionals and policymakers, and more importantly, had a direct impact on the lives of millions of people in the developed and developing world.

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend (and discuss) the presentation of the New Fiscal Transparency Code and Evaluation, a policy tool that is “designed to ensure that policymakers, legislators, citizens, and markets have a complete picture of the state of public finances, covering the entire public sector, incorporating accurate and comprehensive fiscal forecasts, and recognizing all major fiscal risks.” (see Richard Hughes, here)

This policy tool, which builds on the success of the ROSCs, is a clear step forward from previous work. In particular, (i) it focuses on outputs rather than processes; (ii) it pays closer attention to different levels of country capacity (moving away from the one-size-fits-all approach); (iii) its recommendations are based on criticality and importance (it focuses on what matters for each country, which should improve targeting and efficiency in the implementation of recommendations), and: (iv) it will provide a picture of the entire public sector.

Given numerous posts and material discussing the details and advantages of this new framework, I will focus here instead on some of the issues I believe should be taken into account regarding the use of this tool. Particularly, I think it’s important to understand how far this framework can take us (i.e., how much could transparency really deliver) and what complementary analyses would make this framework more effective when making recommendations and trying to help countries move forward.

The Value of Transparency and Information

Increasing transparency and the availability of information has a value both in and of itself, and as an ingredient that can help people make better decisions. As the IMF’s website describes, “transparency is critical for effective fiscal management, and helps ensure that governments have an accurate picture of their finances when making economic decisions, including of the costs and benefits of policy changes and potential fiscal risks. It also provides legislatures, markets, and citizens with the information they need to hold governments accountable.” The same website also states, “better fiscal transparency will help countries across Latin America and other regions in the move to more stable economic growth”. (Emphasis added)

However, stating that it “will help” instead of it “may help”, or that it “helps ensure” instead of it “may help” assumes much about the workings of public institutions and the polity in general. First, it assumes that decisions are made in settings that matter. That is, for example, having more information for Congress, or having a Congressional Budget Office, matters only if Congress makes a real impact on decision-making. If Congress is a passive actor that rubber stamps whatever comes from the Executive branch, then more information and transparency can have little impact. Examples abound from the developing world where this is the case.

Second, it assumes that somebody cares about the longer term. That is, that actors favor the long-term impact of the actions taken today, for which having more information matters, such as taking decisions on the structure of government-funded pensions or other welfare benefits. However, in many cases, governments’ unsustainable social security systems, indiscriminate use of windfall revenues, lack of rainy day funds, and procyclical policies are not the result of lack of data but of their short-term vision. This political equilibrium has multiple causes, including very unstable political regimes or government tenures, or the absence of institutionalized and programmatic political parties that internalize the decisions of those in office today.

Third, it assumes that somebody monitors and controls. That is, it assumes that the country has an array of well-functioning oversight and control institutions, such as an effective legislature and an independent audit agency, with influence over the decisions and actions of government. Many countries lack these important oversight and control mechanisms.

Fourth, it assumes that somebody cares. That is, that electoral systems are not clientelistic and biased and citizens reward those who pursue the right policies instead of voting for those who provide short-term clientelistic benefits, even at the expense of bankrupting the country.

Finally, it assumes that those who care can get together. In other words, that there is a working civil society with links to decision makers and the media that reduces collective action problems. Otherwise, no matter how much information is provided, people have little chance to react and hold governments accountable. Consequently, moving from “may help” to “will help” requires investments in many more dimensions than increasing transparency.

From Information to Recommendations

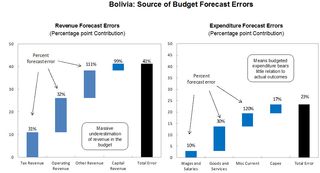

Providing more information undoubtedly creates the conditions for asking the right questions and focusing on what really matters, but sometimes it must be accompanied by additional research. The IMF’s new transparency framework provides a good example of this by presenting very clear and concise information about budget forecast errors, as shown in the Figure (Source: Gupta, Schwarz, and Pessoa (2014), New Fiscal Transparency Code and Assessment).

The results shown in the Figure for Bolivia are not unique to that country. One can argue that these large discrepancies between forecasts and revenues and between budgeted expenditures and actual outcomes reflect the limited capacity of those charged with making the estimates used in the budget. However, experience shows that often this is not the case, particularly when the governments repeat the same “errors” (under or overestimating) over and over again, and these errors are suspiciously aligned with the incentives of policymakers. For example, presidents who are granted by law the ability to spend excess revenues have incentives to underestimate revenues so they can pad a discretionary cushion to either build coalitions (the executive branch directs funds to those who support the government agenda) or pursue electoral and clientelistic policies, without having to share the political gains with Congress. Other reasons for the “errors” can be traced to political theatre before the elections, or bargaining among different coalitions in government. Therefore, it is usually not the lack of data or capacities that drives the drafting of the budget but the search for a political equilibrium.

Sometimes the discretion to spend or tax serves clientelistic purposes and it should be reined in. In such cases, recommendations to reduce discretion would help the country. Other times, discretion is the only way sitting governments can build coalitions and govern, and in such cases international institutions should abstain from pressing for reform unless alternative solutions to the real problem are offered too (e.g., electoral reform may have to accompany any recommendation regarding reducing discretion).

Summarizing, the new framework is a very valuable effort and a leap forward. First, it focuses on outputs instead of procedures. But it is important as we move along this path of increasing transparency that we manage expectations regarding how much can be achieved. Usually, low transparency is a symptom of problems that would prevent more information from having any impact anyway.

Second, the new framework is right in acknowledging differences in country capacities, but before offering recommendations on what countries should do we need to have a full diagnostic that goes beyond the scope of the new transparency framework. It is important that such analyses go further than the characterization of problems and easy fix solutions to an understanding of why the countries are where they are in the first place. For example, why do countries invest so little in strengthening capacities, what determines the political equilibrium, and so on?

Finally, recommendations for reform may need to cover a broader range of issues, and dig deeper into institutional constraints, than the conventional array of solutions familiar to PFM practitioners. For example, sometimes effective change will only become possible if the government is prepared to invest in areas such as civil service capacity building, third-party enforcement, and the independence of the judiciary.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.

[1] Carlos Scartascini is a Principal Economist at the Research Department of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The opinions expressed in the note are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IDB, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent. For more information on the author and his publications, see www.cscartascini.org ; and for a discussion of political economy issues relevant to the present note, see a previous PFM blog article (http://blog-pfm.imf.org/pfmblog/2014/01/politics-matterbut-pfm-reforms-do-too.html).