Posted by Benoit Taiclet and Lewis Murara

Program-based budgeting (PBB) is considered an important tool for developing countries to channel more efficiently their resources to achieving their development goals. However, PBB is also a rather sophisticated PFM reform, especially when certain public finance management (PFM) basics still need to be improved. Burkina Faso and Mali offer interesting examples of low-income countries whose reforms started at different stages, but finally made good progress both in program budgeting and more general improvement of their respective PFM systems. This success –although it must be stressed that PPB is not yet fully functional - mostly relies on the countries’ own determined pursuit of reform. However it has been facilitated by the synergy built between several stakeholders, the IMF and its Regional Center AFRITAC West, the UNDP and its regional pole in Dakar, as well as bilateral partners such as the Belgian, German and Japanese governments.

Gradual reform or a more risky Big Bang approach?

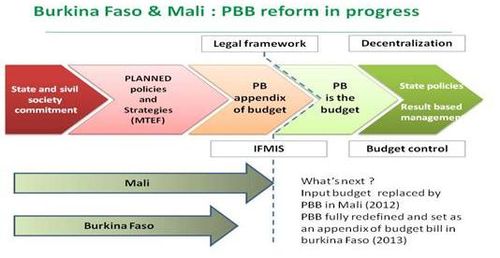

Both countries chose at an early stage a similar, cautious multi-step scheme for reform. The first step was to ensure a strong state commitment and civil society backing, then to develop costing of policy expenditures and medium term expenditures frameworks. In this scheme PBB was planned to be developed alongside the usual input budget prior to its full implementation. So far Mali has - and Burkina Faso intends to - set up a comprehensive PBB budget as an appendix of the draft budget bill. But still this appendix remains an information tool and to some extent a planning tool only, for the Executive, Parliament and the donor community; it has, however, not yet been considered an appropriate tool to actually manage government financial resources and to monitor the performance of the services.

A further step in the reform process is to have the result-oriented budget fully operational. In our view this would require:

- updating the legal framework in accordance with the WAEMU legislation;

- adapting the financial information systems to the new program classification;

- giving agencies and program managers more initiative and power in the process of expenditures, while at the same time relaxing ex ante controls of the ministry of finances;

- using the result based management framework, including performance indicators, for allocative decision-making, program management and policy review.

Depending on the situation of the country, the next step to full implementation may also be gradually implemented, the line-item budget remaining either as a presentational aid or even the main instrument to execute programs in the short term.

Both countries have made remarkable progress in PFM reform

- Mali: since the early 2000s, the Malian government has presented to the Parliament, monitored and regularly reviewed a result-oriented budget alongside the line-item budget. The country recently reviewed 29 line-ministries program structure and aligned indicators so as to improve the PB budget presentation, the performance frames and the apportionment of resources. The government also prepared draft bills to update its core PFM legislation in accordance with the WAEMU[1] legislation. The National Treasury is currently rolling out a computerized accounting system designed to handle the new WAEMU classifications. Furthermore, Malian authorities expressed their intention to move forward and have its result-oriented budget fully operational timely with WAEMU legislation (i.e. between 2012 and 2017).

- Burkina Faso: the parallel program based budget developed in the 2000s eventually lost its consistency with the line item budget. Against this background, the Burkinabe government started a comprehensive reshaping of its former program based budget in 2010. The government’s intention was then to add a result-oriented budget appendix to the draft budget for 2013 and to transmit it to the Parliament as additional information. So far 37 Ministries and constitutional institutions have held workshops to rewrite their programs. Their result-oriented draft budgets are presently at various stages of development. As in Mali, Burkina Faso authorities are about to update the national legislation to meet WAEMU harmonized public finance legal framework.

Moving forward requires a solid PFM foundation to limit risks.

Hasty implementation of PBB can be quite risky. Accounting and information systems need to be adapted, expenditure procedures and controls reformed, and authorities and capacities of managers enhanced. In some cases early introduction of PPB has actually stalled the PFM reform process. This is why the IMF/Fiscal Affairs Department, while backing better budget preparation and execution in low income countries, has long advocated a prudent approach, giving priority to solid PFM foundations, such as a realistic annual budget presented according a sound economic classification, effective line item budget execution controls, reliable fiscal reports, and strong cash management. For full introduction of PPB, Mali and Burkina Faso thus will have to face the challenge of coping with basic weaknesses that still undermine the PBB reform: rolling out the accounting application and ensuring it is fully interfaced with the budget information system, which itself needs to be adapted to handle programs (Mali); improving fiscal reporting, notably according to the programmatic format, also in-year (Burkina Faso and Mali), and adapting expenditure control rules; and optimizing cash management with the reestablishing of a treasury single account (Mali).

[1] West African Economic and Monetary Organization ministers agreed in June 2009 on a series of six “directives” covering: budgeting, fiscal reporting, nomenclatures (budget and accounting) and public financial statistics. The directives should be transposed in domestic laws no later than 1/1/2012, with prescribed reform measures to be progressively implemented from 2012 to 2017.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.