Posted by John Zohrab[1]

The new fiscal risk[2] provisions of the IMF’s revised Fiscal Transparency Code (English, العربية , Español, Français, Português) are resonating in Central Asia and the Caucasus. They are stimulating increased efforts to improve and expand fiscal risk disclosure.

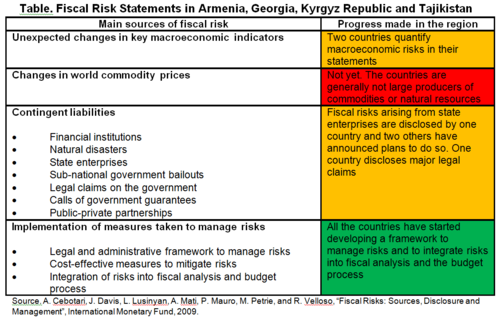

Armenia, Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan present fiscal risk statements to parliament in their annual budget documentation. These statements – which are typically published on the ministry of finance websites – are a substantial step forward in meeting international good practice (see table below).

To be specific:

- Armenia’s statement is an update of the disclosure in its MTEF document published and presented to parliament several months before the annual budget.

- Armenia’s and Georgia’s statements currently disclose macroeconomic and public debt fiscal risks, and in both countries the authorities intend to expand their disclosures in the 2016 budget documentation to include non-financial corporation fiscal risks.

- The Kyrgyz Republic’s statement currently discloses a series of specific fiscal risks relating to accession to the Eurasian Economic Union, external financing, loan repayments, pending court cases, exchange rate movements and unfunded expenditure mandates.

- Tajikistan’s statement currently discloses large public corporation fiscal risks.

All countries in the region are aware that the statements increase fiscal transparency, strengthen PFM and make fiscal policies more stable. This in turn improves the countries’ access to capital, from both official and private sources, both debt and equity, with favorable consequences for economic growth.

One of the principal challenges in producing the statements is anticipating the response to the information they contain. One of the legacies of the USSR’s central planning system is that budgets and fiscal forecasts are still widely regarded as targets. As a result, disclosing downside fiscal risks is often seen as admitting the possibility of failure.

Disclosure may also be seen as spreading bad news. For example, a ministry of finance publishing an economic scenario in which the exchange rate has depreciated by 30% might not be met with indifference by a population whose savings and pensions have in recent memory been wiped out by hyperinflation. Nor might the publication by the ministry of finance of a public corporation’s Z-score (a prediction of bankruptcy) be welcomed by the corporation’s management and board of directors. It is one thing for negative scenarios to be disseminated by organizations external to the government, but quite another for them to be published by a ministry of finance.

Viewed from an external perspective, however, there is a thirst for information on fiscal risks from members of parliament, the mass media and civil society, not to mention actual and prospective investors and lenders both inside and outside the countries. Moreover, the presentation of the information has to be tailored to the audiences. A massive information dump would be counterproductive. Data that are released must be informative and authoritative, be presented and explained clearly, but not so technical as to lose the attention of audiences that are not specialists in financial matters.

In order to balance these various considerations, the preparation and publication of fiscal risk statements in the region are managed with great care by the ministries of finance. The authorities appreciate that, if handled well, the statements could help institutionalize greatly improved PFM and fiscal policy procedures. On the other hand, finance ministries also express concern that, if handled poorly, fiscal risk statements could undermine the reform process and complicate the development and presentation of economic and fiscal policy.

Another challenge in the region has been to develop robust procedures for collecting the required information. Some of the data - for example on the risks associated with macroeconomic developments and public debt – should be readily available to the finance ministry. On the other hand, the collection of information from public corporations can be a complex exercise, often involving line ministries and other agencies. In order to focus their efforts on risk assessment and management, ministries of finance typically seek to maximize the involvement of other ministries and agencies in the information collection process, but this requires extensive collaboration and coordination.

The statements typically seek to standardize the risk assessments they present. Thus, the analytical framework for the disclosure of information on macroeconomic and public debt fiscal risks – for example on the quantification of economic and fiscal shocks and the analysis of alternative scenarios - are consistent with those published by the IMF in relevant country reports. Similarly, the analytical framework for quantifying the fiscal risks associated with public corporations uses a range of indicators that follows internationally-accepted approaches. Standardization of risk assessment methodologies improves the understanding and credibility of the statements themselves.

Countries may use fiscal risk statements as a means of educating the public to both potential fiscal policy adjustments and desirable policy reforms. For example, in Georgia, the macroeconomic policy section of the fiscal risk statement analyzes the government’s possible fiscal response to various scenarios. In Tajikistan, the statement of public corporation fiscal risks discusses possible measures to eliminate quasi-fiscal activities and improve the corporations’ financial performance, which helps to focus the public’s attention on desirable reforms. In the Kyrgyz Republic, the statement of fiscal risks concludes with a list of fiscal risk mitigation measures that the authorities plan to implement during the following three years. In Armenia, the possible need to reduce lower priority expenditures in the event of adverse macroeconomic developments is emphasized.

The capacity implications for ministries of finance of preparing and publishing statements of fiscal risks are significant. They need to create sufficient capacity to produce the statements regularly using appropriate and up-to-date analytical approaches, and to manage related communication issues. Technical assistance may be useful initially in developing the methodological framework for preparing the statements, but the ministries of finance have to be ready to sustain their preparation without external assistance.

Viewed overall, the experience so far of Armenia, Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan has been encouraging. However, there is a long way to go. It will be many years before the countries in the region will be producing fiscal risk statements that conform to all the advanced practices of fiscal risk disclosure identified in the IMF’s revised Fiscal Transparency Code. In the meantime, the reforms of accounting and reporting systems that are planned in the region, and the countries’ longer-term ambition to develop whole-of-government financial statements, will help them move toward this goal.

[1] IMF, Fiscal Affairs Department, Regional Advisor for Public Financial Management, Central Asia and Caucasus (jzohrab@imf.org).

[2] Fiscal risks may be defined as deviations from the fiscal outturn projections presented by the government in the budget and other official reports.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.