Posted by Taz Chaponda[1]

The problems associated with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are well known. They are very costly to run, few of them make profits, or if they do, they tend not to pay dividends on a consistent basis. This problem is more applicable to developing countries and emerging markets than to advanced economies. In the latter, deregulation has sharply reduced the number of SOEs and improved their performance. But in emerging markets, SOEs are still pervasive and their failure can result in huge economic and fiscal costs. Given these risks, why do governments continue to keep them?

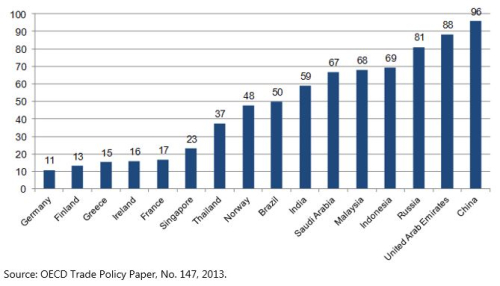

To understand the ubiquitous nature of SOEs, it is necessary to go back in history to when governments set up dedicated entities to provide services that were viewed as having some “public good” characteristics, or where natural monopolies existed. It was argued, that certain essential services could not be left to the private sector as it would not supply these services reliably to everyone that needed access (think of public utilities). Another argument was to promote industrialization by investing in strategic sectors through SOEs. Economies in East Asia led the way in this respect. The chart below shows countries with the highest SOE presence among their top ten firms.

Figure 1. SOE shares among countries’ top ten firms (%)

These and other arguments do have merit. However, what may have been a sound case for setting up a public corporation several decades ago may no longer hold where new solutions have emerged through better technology and business innovation. For example, in areas such as affordable housing or even energy generation, private sector innovation has led to new possibilities (think of Green mini-grid systems). This calls for a careful re-assessment of the policy objectives underpinning each SOE and interrogating whether the original business models are still valid.

It is also worth considering market and technology developments that may have rendered some combination of public and private provision more viable than an exclusive public-provider model that relies on the budget. Consider power generation which can readily accommodate public and private production, reducing the risks for the public sector while providing choice to consumers. Moreover, where state-run utilities cannot reach everyone economically, mini grids and off-grid systems can fill the gap. These trends suggest that large vertically-integrated power utilities under state ownership should be reevaluated.

Going back to re-examine the policy objectives helps to clear the “fuzziness” that clouds decision making related to SOEs. It disentangles the purely social objectives from the commercial and strategic objectives, and informs how different types of entity should be funded and managed. Clearly, the commercial ones should operate independently of the government budget and should be properly regulated. If a commercial SOE is unable to generate a reasonable return without frequent government support, its business model and structure is likely to be inappropriate. It may also continue to be a drain on the budget, to the detriment of other essential public services such as health and education.

Given the complex political economy surrounding SOEs, there are few easy answers, especially when an entity has high fixed costs and a debt portfolio guaranteed by the government. The pace of reform will differ from country to county, but it should be based on a clear set of financial information on the current and future risks associated with each entity. These risks can be formally assessed through a cost-benefit framework, modified to reflect any externalities associated with an SOE.

In emerging markets, SOEs may not readily open their books to scrutiny as they tend to be less transparent than their private sector counterparts. To address this problem, governments should start by making the operations of SOEs fully transparent to taxpayers. Transparent in terms of the actual cost of services being provided, as well as the risks being carried by the government. This risk-adjusted cost should be compared to the benefits of the services being provided – adjusting for any positive externalities associated with such services.

A cost-benefit approach can be more usefully applied to selected services or businesses within the SOE. By looking at business units separately, there may be scope for retaining those that are based on sound economics, while restructuring or closing those that are too costly and outdated. Performing a cost-benefit analysis on the entity and its individual business units shows the impact of cross-subsidies within the SOE. This analysis makes the trade-offs explicit, thus allowing policy makers to design and implement practical reform solutions.

An example of different approaches to SOE management is provided by prominent state-owned airlines across Africa. With one exception, Ethiopian Airlines, the others regularly lose money and rely on government bailouts, while a few countries are choosing to enter strategic partnerships to manage their fleet and share financial risks.

The proposed approach still does not address why governments keep SOEs, even when the fiscal impact is large and negative. The reason lies partly in the lack of accurate, timely, and transparent financial information, which hides the true cost of state ownership, while overstating the perceived benefits. This opacity also perpetuates poor decision-making and service delivery models that are outdated and costly. Ultimately, SOE reform depends on political decisions, but generating sensible reform options depends on weighing up the costs and benefits.

[1] Senior Economist, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.