Posted by Victor Lledó[1]

Fiscal rules and fiscal councils have been increasingly recognized as important tools to promote sound fiscal policies.[2] By constraining discretion and fostering transparency, they enhance fiscal discipline and make fiscal policy more predictable. In particular, fiscal rules can help governments establish fiscal targets that support fiscal sustainability, while fiscal councils help ensure those targets are realistic.

Together, they can raise the financial and reputational costs of deviating from the announced targets. In doing so, they help prevent excessive fiscal deficits and unstable debt dynamics. Fiscal rules and fiscal councils also contribute to improve fiscal behavior over the business cycle and encourage better risk management as building buffers in good times makes space to conduct countercyclical policies in bad times and to absorb the realization of fiscal risks. Healthy and resilient public finances, in turn, give policymakers the room needed to serve other objectives, including economic efficiency and growth, as well as achieving a more equitable distribution of income.

Tracking and benchmarking fiscal rules and councils

Starting in 2009, in the case of fiscal rules, and 2013, in the case of fiscal councils, the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department, in an effort to account for the prevalence, incidence, and features of fiscal rules and fiscal councils across IMF member countries, created and periodically updated databases on fiscal rules and fiscal councils.[3]

These two datasets provide the most comprehensive source of international comparison for policymakers and researchers interested in either of these fiscal institutions.[4] Previous vintages have become a reference among government officials and PFM experts interested in designing, implementing, benchmarking, or reforming fiscal rules and councils in their countries. They have also been used in policy and research circles to understand the impact of these fiscal institutions on fiscal performance.

The fiscal rule dataset includes information on (i) the year rules were adopted, reformed or discontinued; (ii) their legal origin; (ii) the coverage of their fiscal aggregates; (iii) their flexibility to shocks (e.g., through cyclically adjusted fiscal targets or escape clauses); and (iv) their supporting procedures (such as the monitoring of compliance with the rule, independent formulation of fiscal assumptions in the budget, and formal enforcement procedures). The latest dataset— just posted at the IMF fiscal rules website — includes information on national and supranational fiscal rules in 96 countries from 1985 to 2015.

The latest fiscal council dataset — just uploaded to the IMF fiscal council website — describes key features of 39 institutions identified as fiscal councils (as of end- December 2016) across the Fund’s membership. The dataset includes key features in the design of fiscal councils such as (i) their remit (e.g. fiscal forecast preparation and assessment, analysis of long-term fiscal sustainability, and monitoring compliance with fiscal rules); (ii) the instruments available to fulfill their remit (e.g. public reports,media visibility, formal consultation and hearings); (iii) their degree of independence (both legal and operational); and (iv) their available resources (e.g. composition, appointment, a term of high-level staff, number of technical staff).

Letting the data speak: A preview

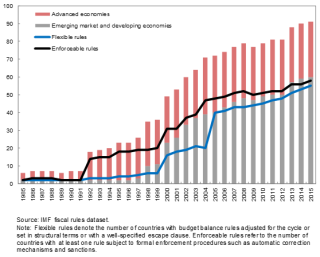

A first look at this latest of update of the database on fiscal rules reinforces three important trends (Figure 1). First, the number of countries adopting fiscal rules continues to increase, consistent with the growing recognition of fiscal rules as a credibility-enhancing tool. As of end-December 2015, 92 countries had fiscal rules, compared to 6 back in 1985. Second, most of the new fiscal rule adopters are emerging market and developing countries, where public demand for fiscal policy credibility is well-known to be higher. There are currently twice as many emerging market and developing economies than advanced economies with fiscal rules. Third, the quality of fiscal rules— measured by the inclusion of effectiveness-enhancing features — has also improved at least in two areas: flexibility and enforceability.

Rules have continued to become more flexible, as more countries started to adopt rules that can be adjusted for the cycle and that introduce well-specified escape clauses. At the same time, fiscal rules have also become more enforceable, reflecting adoption of sanctions and automatic correction mechanisms. Jamaica exemplifies these three trends. A developing economy in pursuit of a more credible fiscal framework, in 2014 Jamaica adopted two rules that aim to (i) bring the debt below 60 percent of GDP by 2025 and (ii) achieve a fiscal balance by 2018. The latter rule includes a well-defined escape clause to make it flexible in the event of large economic shocks and an automatic correction mechanism that triggers remedial measures when the debt ceiling is at risk of being breached.

Figure 1: Fiscal Rules by Selected Categories, 1985-2015

(Number of countries with at least one fiscal rule)

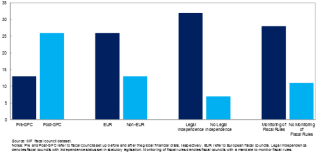

A preliminary analysis of the most recent vintage of the fiscal council dataset reveals three interesting facts (Figure 2). First, two-thirds of the existing fiscal councils were established after the global financial crisis (GFC). To a large extent, this reflects post- GFC reforms aimed at restoring the credibility and sustainability of fiscal policies (Debrun and Kinda, 2014). Second, unlike fiscal rules which have spread worldwide, the rise of fiscal councils is still mostly a European — and hence an advanced economy — phenomenon. Two-thirds of the existing fiscal councils are located in Europe. European fiscal councils also account for ¾ of the post-GFC fiscal councils (20 out 26). [5] This partly reflects a requirement for European Union (EU) member states — imposed on the back of reforms in the EU fiscal governance system in the aftermath of the euro area debt crisis — to establish national independent bodies to monitor compliance with fiscal rules and produce or at least assess or validate macroeconomic and budgetary forecasts. This last point helps explain the third and last fact unveiled in the fiscal council dataset: safeguarding fiscal councils’ independence in legislation and mandating them to monitor fiscal rules is becoming the norm.

Figure 2: Number of Independent Fiscal Councils by Selected Categories, 2016 (click image to enhance)

Forthcoming work in the Fund will look at recent development related to fiscal rules and fiscal councils in greater depth, with a view to provide clear guidance to policymakers on how to design, implement, and reform these institutions in the pursuit of more effective fiscal policies.

Stay tuned!

[1] Senior Economist, Fiscal Policy and Surveillance Division, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2] A fiscal rule is a long-lasting constraint on fiscal policy through numerical limits on budgetary aggregates (IMF, 2009). Fiscal councils are defined as independent, non-partisan agencies with an official mandate to assess fiscal policies, plans, rules, and performance (Debrun and others, 2013).

[3] The fiscal rule dataset was updated in 2012 and 2015; the fiscal council dataset in 2015.

[4] With respect to fiscal rules, another important source is the European Union (EU) Commission database of fiscal rules. With respect to fiscal councils, alternative sources include the EU Commission database of independent fiscal institutions and the OECD database on independent fiscal institutions. Coverage in all these sources is limited to EU and OECD members, mainly advanced economies.

[5] As in the case of fiscal rules and measured by the growing interest for fiscal councils in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDE), this “Euro-dominance” is not likely to last long. Colombia, Uganda, South Africa, and Peru are among recent EMDE adopters.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.