Posted by Andrew Bauer and Sofi Halling[1]

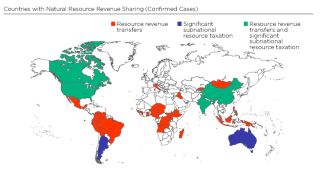

In nearly every country, subnational governments receive public funds, either through direct tax collection or intergovernmental transfers. But in more than 30 countries—from Bolivia to Canada to DRC to Indonesia—policymakers have chosen to create a special revenue sharing system to distribute non-renewable natural resource revenues (see map below). A recently published report by the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) examines this important topic (NRGI link to report; UNDP link to report).

In most of these countries, oil-, gas- or mineral-producing regions receive a percentage share of the production value extracted from their territory. In a subset of these countries—including Ecuador, Mongolia and Uganda—resource revenues are pooled separately from other fiscal revenues and distributed according to a unique formula that includes, for example, poverty and population indicators. Every year, hundreds of billions of dollars are distributed through these systems.

Economists might wonder why some subnational governments receive a share of natural resource income when they do not receive a share of, say, auto industry or forestry sector income. After all, resource taxes and royalties are generally more volatile than other sources of revenue; and local dependence might lead to harmful boom-bust cycles. Resource revenue sharing systems can also lead to income inequalities between resource-rich and resource-poor regions and generate tensions between those with and without natural resources.

(click image to enhance)

In many ways, economists’ concerns are justified. There is evidence that derivation-based resource revenue sharing—where a share of the revenues goes back to its area of origin—may have no impact or even a negative impact on regional economic performance in some contexts. Studies carried out in Brazil, Colombia and Peru showed that housing, education and health outcomes, as well as economic growth, did not improve following the collection of large oil or mineral revenue windfalls by subnational governments. In Brazil, for example, access to piped water, rubbish collection and connection to sewage networks decreased as more oil revenues flowed into municipal coffers.

Worse, poorly designed revenue sharing systems can incentivize groups to seize control of extractive sites to access a higher share of revenues. The proceeds can then be used to finance violent conflict. For example, between 2005 and 2008, when mineral prices soared, some local leaders in Peru instigated violent protests in order to gain jurisdiction over mine sites and collect additional transfers from the central government.

Yet there are valid political reasons for introducing resource revenue sharing. First and foremost, these systems can mitigate or even prevent conflict, particularly where that conflict has been fueled by natural resource wealth. In Bolivia, Brazil, the DRC, Indonesia, Mongolia, Nigeria and Papua New Guinea, they have encouraged rebel groups or secessionist movements to engage in technocratic discussions over revenue sharing rather than resort exclusively to violence. Furthermore, policymakers can use these systems to promote economic development in resource-rich regions and compensate local residents for the environmental damage, loss of livelihoods and depletion of subsoil assets associated with resource extraction.

Resource revenue sharing systems often suffer from several PFM-related weaknesses, in addition to the revenue volatility generated at the local level. These weaknesses include ‘fiscal mismatch’, and lack of legal clarity, transparency and oversight.

Derivation-based fiscal transfers are neither linked to subnational financing needs nor the expenditure responsibilities of subnational governments. Indeed, they undermine key principles of sound financial management such as the ‘finance follows function’ rule. This often leads to a situation where local governments receive revenues that far exceed their absorptive capacity or needs. The result is generally wasteful spending of scarce resources.

The lack of codified distribution formulas, transparency and oversight over fiscal transfers means that in many countries—including the DRC and Philippines—subnational government do not receive the amounts to which they are entitled. This leads to greater distrust and, sometimes, conflict between levels of government, undermining any ‘peace dividend’ generated by these systems.

While NRGI and UNDP do not advise governments to simply adopt other countries’ systems, we do advise learning from their experiences and “mixing and matching” elements that work well in similar situations. In our report we offer 10 recommendations, mindful that each country is unique. For example, we suggest that policymakers select the types of taxes and revenues to share based on ease of collection and verification. We also advise smoothing expenditures when implementing derivation-based systems, and reaching a national consensus on the revenue sharing formula. While these systems will remain political, injecting some economics and good governance standards might go a long way to improving public welfare.

[1] Andrew Bauer is a senior economic analyst at the NRGI. Sofi Halling is a policy analyst at UNDP.

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.