Posted by Taz Chaponda[1]

The International AIDS Conference in July 2016 reported a resurgence of the disease, particularly in Africa and South Asia[2]. The number of people becoming infected every year, which had been dropping, has now stalled and is rising in some countries. Just under 2 million people become HIV positive every year; as the epidemic continues to grow, the cost of keeping people alive continues to rise. UNAIDS has reported that funding from donor governments fell last year for the first time in five years, from $8.6bn in 2014 to $7.5bn in 2015. This raises questions about the efficacy of current funding models, and the implications for fiscal sustainability in those low-income countries that have a large proportion of the population on HIV/AIDS treatment. Most of these countries are in Africa and Asia.

Fiscal Space

The concept of fiscal space is closely associated with the ability of governments to maintain debt sustainability. A rising public-debt-to-GDP ratio becomes a concern if the country’s primary balance does not keep pace with higher effective interest payments as this could lead to explosive debt levels. Large shocks to the economy (such as wars or natural disasters) could trigger a fiscal crisis and lead to an unsustainable public debt position. One major shock that is often overlooked is the debt burden associated with treating infectious diseases like malaria and AIDS, particularly in developing countries.

Fiscal Implications of HIV/AIDS

Paul Collier and his fellow researchers have raised the issue of growing fiscal risks in Sub-Saharan Africa due to the fiscal implications of HIV/AIDS treatment using antiretroviral (ARV) drugs[3]. They identify these risks as a “potential fiscal calamity”. The authors make two important points about the treatment of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa. First, because “the decision to start treatment locks in the need to finance future provision, that future liability needs to be known in advance”. The authors propose a way to quantify the expected fiscal liability associated with treatment and present some dramatic empirical results.

Second, the authors note that “because the continuing spread of infection creates large future liabilities, there is a new rationale for prevention policies. While no longer medically essential to prevent death, prevention becomes more financially valuable. It is worth expanding spending on prevention at least until an extra dollar averts a dollar of liability from new infections”.

Eight African countries were examined as part of the study. The researchers calculated the aggregate fiscal cost of future treatment as the net present value (NPV) of the estimated costs over the period 2015-2050, plus a terminal value. The results show a sharp rise in the fiscal cost of treatment from 1-2 percent of GDP in 2015 to as much as 74 and 80 percent of GDP for Lesotho and Malawi respectively. Larger countries seem to fare better — the estimated costs for South Africa and Nigeria are 21 percent and 7 percent of GDP respectively, though still much higher than now.

A key recommendation from this study is that donors and governments should closely align the share that each takes of the costs of treating future infections and of the costs of prevention. In other words, neither party should focus solely on treatment or prevention, as both are important. Unfortunately, prevention has historically been neglected relative to the billions of dollars spent on treatment.

However, leaving this growing fiscal challenge to governments and donors may not yield sufficient resources to mitigate the substantial risks identified by the researchers. Bringing in the private sector as an essential third party should also be considered. Although financing of disease prevention is not an easy fit for private investment, social impact investors who seek a return beyond a financial one could be interested if the opportunity is properly packaged. One possible financial innovation to fill the gap is the Development Impact Bond (DIB), also known as a Social Impact Bond[4].

Social Impact Bonds

Social Impact Bonds (SIB) are a ‘pay-for-success’, or results-based payment mechanism pioneered in the UK prisoner rehabilitation program in 2010. Under this innovative financing model, the outcome funder (government agency or donor) pays a private sector service provider for delivering a social benefit. The preference for using a private sector entity or NGO as a service provider is the realisation of efficiency gains expected from a private operator, compared to a public one.

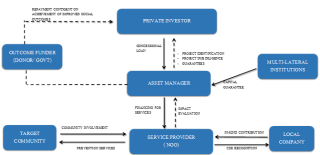

In the last five years, a number of companies and governments have been working together to develop this new model, which uses the money of private investors to accomplish socially beneficial goals. A relevant example is the current deployment of such an instrument in Mozambique to fund malaria prevention strategies. The Malaria DIB is leveraging support from local companies including Nandos, the fast food chicken outlet. The diagram below shows how the typical SIB model can channel private finance to social activities in numerous sectors including health, education, and water provision.

(click to enlarge photo)

Source: Author

SIBs are still in their experimental phase, nevertheless, there is growing evidence that a well-designed SIB, by providing a close link between performance and the realization of returns, could help to strengthen preventive measures for diseases like HIV/AIDS. Without verifiable results, the investors do not get their expected return. Another advantage of this approach is that there is an underlying business case. SIBs are not a charitable activity. However, it may be necessary to include some grant funding or partial government guarantees to increase the viability of the SIB for private investors.

With a traditional SIB, the government contracts a group to administer the bond, and the administrator raises funds from private investors. That money is then distributed

to service providers (usually NGOs with a track-record in that sector). The NGOs use the money to scale up the work they have already been doing to increase its impact across the target community. If certain targets are met — in the case of Mozambique, reducing the rate of malaria infection — the government (or donor) will repay investors with interest. In this way, scarce public funding is spent more effectively due to the close monitoring and evaluation of results.

To date, most of the SIBs have been launched in North America and Europe with very few examples in Africa. If the Mozambique pilot and other similar attempts are successful, there would be a strong case for scaling up this type of funding mechanism to reduce the fiscal burden on governments. There may also be a role for multilateral development agencies to provide partial or full guarantees to crowd in private investors.

[1] Technical Assistance Advisor, Public Financial Management 1 Division, Fiscal Affairs Department, IMF.

[2]http://www.cnn.com/2016/07/19/health/hiv-infections-rise-74-countries/

[3] From Death Sentence to Debt Sentence. Finance & Development, December 2015, Vol. 52, No. 4.

[4] Under a DIB the donor pays for the improved outcomes while the government pays under a SIB

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.