By Richard Hughes[1]

On November 11 and 12, the Overseas Development Institute’s Centre for Aid and Public Expenditure (CAPE) in London will be dedicating its annual conference to the question of how developing countries can get a bigger “bang” for their public investment “buck”. The conference takes place against the backdrop of a surge in public (and private) investment in infrastructure in developing countries in recent years. However, the impact of this latest investment boom on economic and social development will depend crucially on the way in which that investment is managed. Past public investment booms in the developing world have often been associated with “white elephant” projects, time delays, cost overruns, inadequate maintenance, illusive returns, and ultimately fiscal instability and retrenchment.

Will this time be different? On the eve of the 2015 CAPE conference, Richard Hughes, Division Chief in the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs Department and co-author of the Fund’s new policy paper “Making Public Investment More Efficient” explores these issues below.

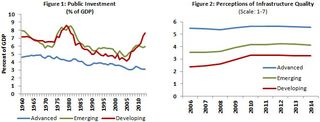

Public investment is a key ingredient in the delivery of many important public services. It builds the schools in which students learn, the hospitals in which patients are treated, and the houses in which many people live. Public investment can also be a catalyst for more economic development by building the transport, electricity, and telecommunications networks that connect households and businesses with economic opportunities both within their countries and abroad.After a steady decline over the past quarter century, public investment levels have begun to recover in emerging market and developing countries, reaching levels not seen since the early 1980s (Figure 1). The rise in public capital expenditure in these countries over the past decade has helped reduce global disparities in infrastructure access, especially to social infrastructure such as schools, hospitals, and water (Figure 2). However, the long-run economic and social impact of this resurgence of public investment depends critically on the way in which it is managed both at the macroeconomic level (to ensure that the overall level of investment and its financing are sustainable) and at the microeconomic level (to ensure that individual projects are fairly appraised, effectively managed, and well maintained).

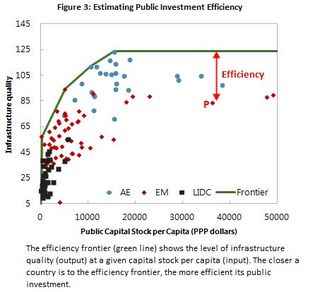

In a new IMF research paper entitled Making Public Investment More Efficient, we found that the average country is losing around one-third of the potential benefits from their public investment to inefficiencies in public investment processes (Figure 3). The potential economic dividends from closing this public investment “efficiency gap” are huge. In the paper we also show that the most efficient public investors get twice the growth “bang” from their public investment “buck” than the least efficient public investors.

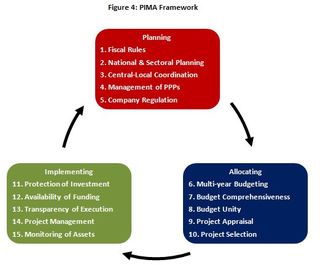

So what can countries do to boost the efficiency of their public investment? In the paper, we identify 15 institutions that shape decision-making at the three key stages of the public investment process (Figure 4):

-Planning sustainable investment across the public sector;

-Allocating investment to the right sectors and projects; and

-Implementing projects on time and on budget.

We go on to show that countries with stronger legal, institutional, and procedural arrangements in these 15 areas also have more credible, efficient, and productive investments. By improving their institutional arrangements in these areas, we estimate that countries can close up to two-thirds of the public investment “efficiency gap.”

What role can the international community play in helping developing countries maximize the economic and social returns from their public investment budgets? Sharing and learning lessons from success (and failure) in managing large infrastructure projects, as we will be doing next week in London, is vital. So is understanding where the weak spots in countries’ public investment management procedures lie, and helping countries to address them.

Here is where the IMF and World Bank can be of particular use to our members. To help countries evaluate the strength of their public investment management practices, we have developed a new Public Investment Management Assessment (PIMA) tool based on the 15 institutions highlighted in Figure 4. The PIMA enables countries to benchmark their public investment management practices against best practice and those of their peers, and develop a targeted action plan for enhancing the efficiency and impact of their capital expenditures. You can read more about the PIMA, which we will be piloting over the course of 2015 and 2016, at www.imf.org/publicinvestment.

In the meantime, I look forward to sharing our work and to hearing about other countries’ efforts to “trap the white elephant” at next week’s CAPE conference.

[1] Richard Hughes is Division Chief of the Public Financial Management Division (M1) in the Fiscal Affairs Department of the IMF

Note: The posts on the IMF PFM Blog should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the IMF or IMF policy.